Brazil’s Indians have been mistreated for as long as anybody can remember. At the same time, dedicated defenders have devoted their lives to the Indian cause. The most famous of these was General Candido Mariano Rondon who became famous for leading expeditions through "Indian Country" and making friends with the Indians as he went. Rondon founded the Indian Protection Service, a government agency created for the purpose of protecting, assisting, and educating "wild" Indians so they could take their places in Brazilian society.

Another man who devoted his life to the Indians died in December. Orlando Villas-Boas, unlike Rondon, thought that remote tribal peoples should be protected by being kept as separate as possible from Brazil’s mainstream. This romantic theory made some sense when Orlando and others were perfecting their techniques of establishing friendly contact with indigenous groups. FUNAI (the agency that succeeded the Indian Protection Service) still does this kind of work through its Department of Isolated Indians. That department’s director, Sydney Possuelo, is quite right to stress that hitherto uncontacted peoples are especially vulnerable and therefore deserve special protection from the outside world; but most of FUNAI’s work has little to do with helping remote peoples as they are introduced to Brazilian society. It deals more with determining what place not-so-remote indigenous groups are permitted to occupy in that society.

Even though Brazil’s indigenous population comprises the smallest percentage of the nation’s total, it has grown dramatically in recent decades compared to those in other nations of the hemisphere. This growth is due to better recordkeeping, the availability of health care, and above all to an increasing desire on the part of indigenous peoples to be recognized and recorded.

Yet this desire for recognition remains a major source of conflict. On one hand Brazil is proud of the Rondonian tradition, according to which its indigenous peoples’ lands are protected and their identities and cultures recognized. On the other hand, the military government that ran the country from 1964 to 1985 sympathized with the ranchers, miners, and smallholders who invaded indigenous lands. The generals felt that these invaders represented the forces of development, in contrast to indigenous peoples and their supporters who "stood in the way of development" and were therefore considered subversive. The result has been that the theoretical protections for indigenous peoples in Brazilian law are regularly offset by practical infringements of their rights. Even when FUNAI was established in response to scandals in the Indian Protection Service, it proved incapable of mounting a vigorous defense of indigenous rights. Instead, the military tried to use FUNAI to "emancipate" Brazil’s indigenous peoples. It expected the agency to demonstrate that indigenous groups and even indigenous individuals had become "civilized" and therefore did not qualify for the special protections that Indians were supposed to enjoy under Brazilian law. The generals tried to promote this policy as being similar and equally beneficial to the freeing of the country’s black slaves (which took place more than 20 years later than in the United States). Indigenous leaders unanimously rejected such "emancipation," however, pointing out that the policy would not free them of anything except their Indianness-from that, they did not wish to be released. On the contrary, they wanted their ethnicity to be recognized and the lands and cultural traditions that went with it to be acknowledged and protected.

FUNAI has continued to be a weak instrument for the protection of indigenous rights. It has been unable to demarcate and protect indigenous lands, as required by law, claiming that it does not have the funds. Since the government regularly allocates insufficient funds for the demarcation of indigenous lands, the fulfillment of this obligation obviously has a low priority.

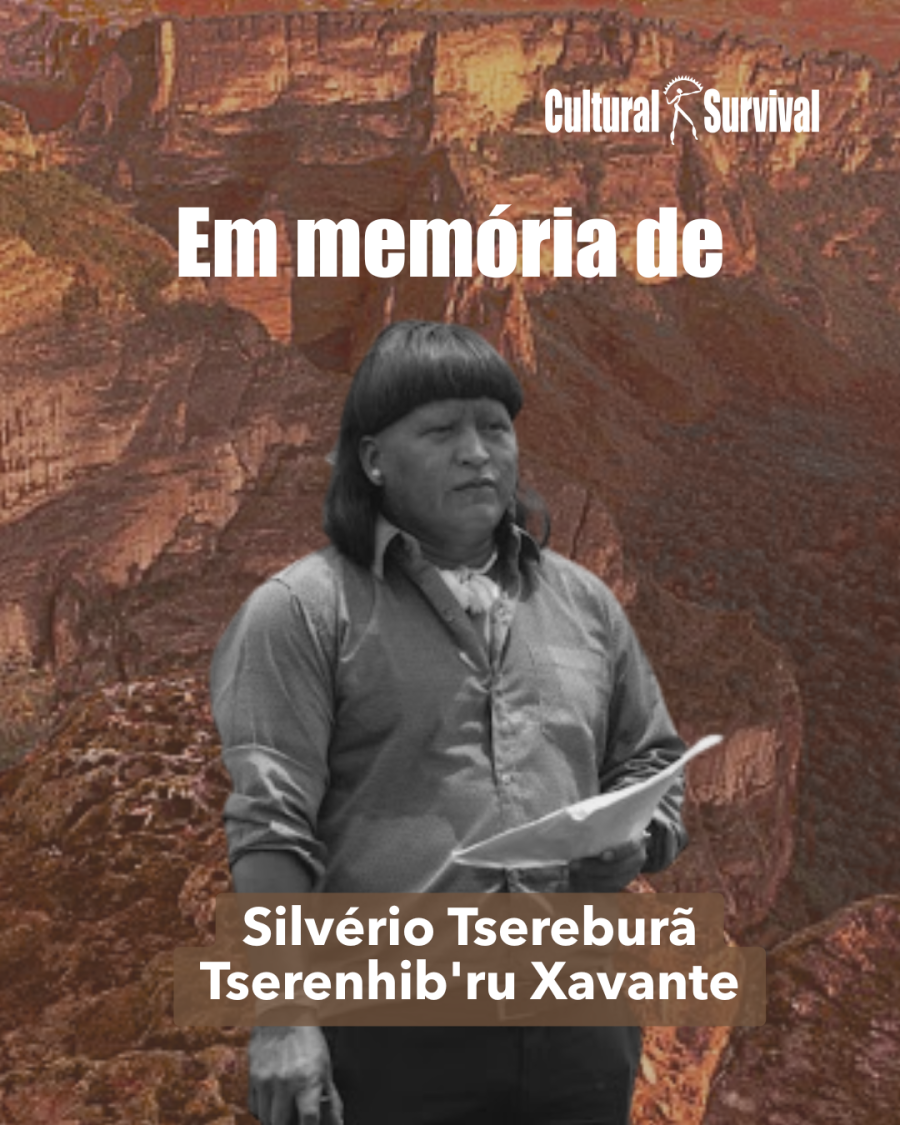

FUNAI has also occasionally been found to be allied with the enemies of indigenous peoples. Recently, a community of Xavante Indians in central Brazil appealed to Cultural Survival for help against invaders of their territory. A Xavante leader had been receiving death threats emanating from a FUNAI official who boasted of his alliance with local politicians who were eager to clear the Indians off their lands. Cultural Survival sent funds to the Xavante and continues to help them mobilize against the FUNAI officials who are supposed to protect them.

The struggle to help the Native peoples of Brazil has moved from quarantining remote groups, as Orlando Villas-Boas spent his life doing, to battling to protect indigenous lands and cultures that face the threat of extinction at the hands of violent neighbors. These modern invaders and their developmentalist allies practice a sophisticated kind of ethnic cleansing. They seek first to rob indigenous peoples of their Indianness and therefore of any rights that should accrue to them under Brazil’s constitution. If this tactic fails they resort to violence, often with the tacit approval of the authorities.

But there is good news. Setting up indigenous and pro-indigenous organizations in Brazil has become easier, and literally hundreds of these organizations have been launched. Indigenous people are therefore in a better position than ever to defend themselves and their rights. Furthermore, the election in fall 2002 of Brazil’s new president, Luiz Ignacio Lula da Silva, brings hope that at long last the rights of the nation’s indigenous peoples will be effectively protected. President Lula, as he is called, takes office with a stated commitment to the poor and to indigenous peoples. Even if his administration merely enforces Brazil’s current laws concerning indigenous peoples, it will go a long way toward realizing General Rondon’s dream of indigenous peoples and others living amicably side-by-side in a Brazilian civilization that has room for all. David Maybury-Lewis is president of Cultural Survival