This article was written in collaboration with the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee as part of a series highlighting the resilience, wisdom, and power of Indigenous communities as they face the climate crisis.

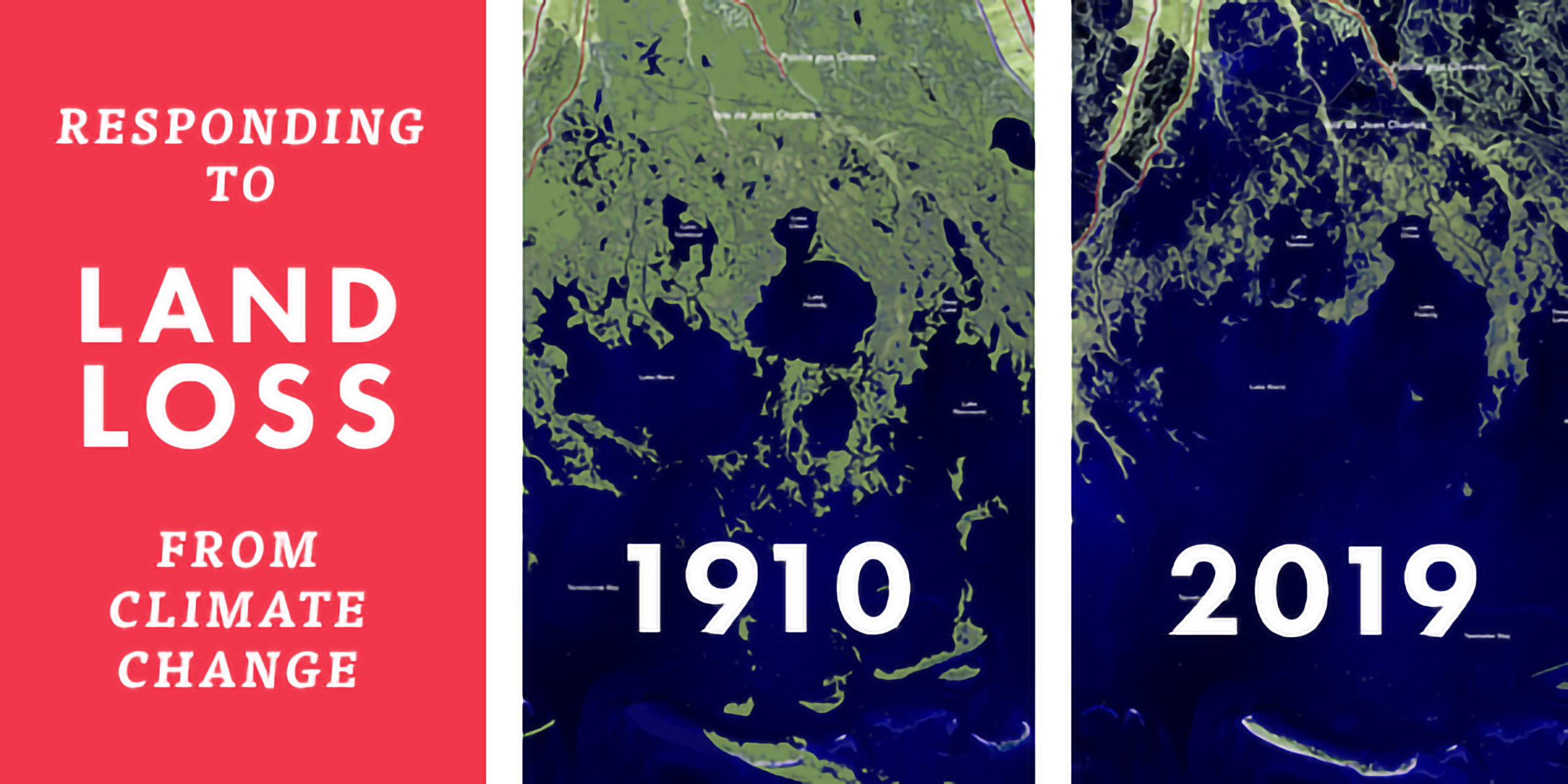

I choose to go out the back door because the woods are still there. The fruit trees, hummingbirds, and bees are still there. It’s a reminder that the people of the coastal bayous in Louisiana are still here. Our way of life is still here, despite the death taking place beyond my front door. When I was little, my brother and sister and I could run through the back yard from our trailer and make it nearly 1,500 feet before we hit the water. Today, when we go back to Shrimpers Row to visit family, my 4 kids can barely make it 400 feet or so before the land starts to disappear into the bayou. I’m only 39.

I grew up in Dulac, Louisiana on a strip of land called Shrimpers Row, part of a community where nearly everyone knew each other or were related to one another. It was our own little world, and it was, in every sense, magical. But climate change has severely battered our physical community, and our traditional way of life is disappearing with it. In the lower parts of our bayou communities, the southeasterly winds bring in water multiple times a year and the flood water soaks our land for days.

At my home in Chauvin, in the upper part of the bayou community where it doesn’t flood randomly yet, we planted squash, okra, and beans. We used several varieties of plant food. Still, plants would barely grow. Finally, using scraps of recycled wood—and in one case the frame of an old trampoline—we created raised gardens in the hopes that something would grow. But these raised beds, which sit one and a half feet above the ground, can only produce certain fruits and vegetables. Further south in our bayou communities of Cocodrie, Dularge, and Dulac, where sudden and severe floods are common, raised gardens never yield anything. And it is only a matter of time before the water comes for the upper communities as well.

My ancestors lived here and were buried in Shrimpers Row. My father, grandparents, baby brother, aunts, uncles, and former chiefs lie here. The flooding is washing them away, too. Our cemetery predates the Civil War. Some of the ground vaults that hold the caskets of our dead relatives and friends have popped out of the ground and floated away. I watched my aunt spend several harrowing days trying to find my uncle’s displaced ground vault and return him to his proper burial spot. Our community is working with an agent to obtain formal ownership of the cemetery so we will be able to locate the site of the graves using markers and geotags. It is only a matter of time before our sacred burial ground is permanently submerged in the floodwaters, with us unable to visit the cemetary in anything but a boat.

We have always been here, since time immemorial. My people had community gardens along the water where every-one could plant what they needed while making sure their neighbors didn’t go hungry. But the federal government does not recognize my Tribe. They say there is no money to protect us, and they will not do what is needed for our people. Our local government has asked us to serve on several committees, tasked us to come up with plans for our own survival. We sit on the Coastal Restoration Committees and participate in workshops like LA Save. We attend numerous meetings across the state at our own expense. When we offered practical solutions rooted in our traditions, we were told we needed science to back it up. When we worked with scientists to support our case, we heard the same thing. There is no money to protect us.

That’s not the case with the predominantly white communities that we can see from our own shores. They have bulkheads to keep the waters at bay and drainage systems to make sure waters that make it over the barriers don’t submerge their streets and homes. We know they don’t get stuck in flood waters watching their septic tanks overflow and their property disappear. And we wonder why we’re not protected in the same way. Why, we ask, are we being punished? Hasn’t enough been taken from us already?

This crisis has forced my Tribe, the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, along with three others in Louisiana: Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw; Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, and Grand Bayou Village of the Atakapa-Ishak Chawasha Tribe; as well as the Inupiaq village of Kivalina, Alaska, to take the unprecedented step on January 15, 2020, of filing a formal complaint with the United Nations Special Rapporteurs on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Peoples and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. We are accusing the U.S. federal government of committing serious human rights violations by failing to protect us from the devastating impacts of climate change while also ignoring the damage oil and gas companies are doing to our land.

The U.S. government’s inaction has resulted in the loss of our ancestral homelands, the destruction of sacred burial sites, and severe and growing threats to our health, food security, and livelihoods. The government has ignored our sovereignty and ability to help shape the future of our communities and our land, placing us at existential risk. Our Tribe is far from the only one suffering because of the climate crisis. We’re living a grim reality that is largely invisible to the world that exists outside the boundaries of our tribal lands. Around the world, millions of members of Indigenous communities are threatened by the climate emergency even though we’ve contributed the least to the industrialization, extractive practices, and overconsumption that have caused temperatures to rise in the first place.

We have concrete requests, though we’re under no illusions about how difficult it will be to see any of them implemented. We want the top UN officials to urge the U.S. to provide new funding to restore tribal lands and hunting and fishing areas, assist Tribes currently working to stay in their homes, and aid those who have been forced to relocate. But we also know the responsibility we have to our own Tribes and to our tribal communities in the U.S. and elsewhere. Indigenous people are members of some of the oldest communities on earth, and our traditions have been passed down for centuries. We have a deep reverence for our land and our way of life. And I can’t sit idly by as those around me suffer—and as my husband and I grow more and more certain that the traditions we celebrated when we were children will disappear before our own children finish growing up.

We know the world they will inherit if we fail to act, and it will be poorer, in every sense, than the one we once knew. I often think of the trees and wild berries that surrounded me when I grew up. My kids can’t see that. Instead what they see are dead trees, just waiting to fall. We owe it to my children—and all of our children—to preserve what is left.

— Shirell Parfait-Dardar is chief of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe in coastal Louisiana.

This article was written in collaboration with the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee as part of a series highlighting the resilience, wisdom, and power of Indigenous communities as they face the climate crisis.

Top photo: Home of Chief Shirell Parfait- Dardar's aunt on Onezia Street in Dulac, LA, during a southeasterly wind flooding

event.