While the power groups and bureaucratic machinery label anyone who protests against the transitional civic-military government as terrorists, Indigenous Peoples and campesinos in Peru only respond loudly, Kachkaykuraqmi! (We continue to exist!) The current situation in Peru describes not a sporadic scene of emotional turmoil, as many believe and attribute, but rather the opening and bleeding of a never-healed historical wound that divides Peru into two worlds: those above and those below, the visible and the invisible, the citizens and the others, Indigenous Peoples, campesinos, Black people, and others.

The legal readings and interpretations fall short of capturing all the social phenomena that are present in this quasi-civil war that Peru is experiencing. The excluded groups that were long questioned as to whether they have a voice or not today demonstrate that they do, but that they are not heard by the State establishment, who only manage to beat their chests and tear their clothes talking about democracy and equality while ignoring or silencing those who gave them that power.The social upheaval in Peru worsened after the political suicide of Pedro Castillo, who, in an act that was almost incomprehensible to the masses who supported him, dissolved the Congress of the Republic without first complying with the constitutional grounds set forth in Article 134 of the Peruvian Constitution. This act was immediately answered by the Congress of the Republic, who, using Article 117 on the grounds for presidential impeachment, immediately dismissed Castillo without observing the due process that, at least in theory, should guarantee a constitutional rule of law.

The Congress of the Peruvian Republic, led by conservative and extreme right-wing parties such as Fuerza Popular (Keiko Fujimori), Renovación Popular (Rafael López Aliaga), Avanza País (Hernando Soto Polar), and others, mockingly celebrated, photographing themselves with the national flag and presenting their detractors the picturesque feat of presidential vacancy. The people, who, in a legal and constitutional disregard, celebrated for a moment the dissolution of the congress, were later horrified by the triumphalist action of the vacancy, which tacitly implied the victory of those who are never allowed to govern, with respect to a president who came from an excluded class; i.e., publicly educated, rural, and with Indigenous campesino identity.

After Castillo’s removal, the presidential succession took place. Dina Boluarte, then the vice president, assumed the presidency of Peru by constitutional invocation. The power groups, including leftist sectors (i.e., urban mestizo), were close to this side of power, which, of course, was qualified as treason by the people, who remembered and expected the initial words of the now president. In the political siege prior to her inauguration, Boluarte said she would leave with Castillo in case he was removed; however, the current first woman president of Peru forgot those words and was quickly co-opted by the parties in power, whom she now worshiped.

The apparent atmosphere in the capital was peaceful, but as the popular saying goes, "Peru is not Lima and Lima is not Peru." The population of the interior of Peru began to organize and convene in response to the arrogance of the Congress. It was not in vain that Boluarte's hometown, Chalhuanca in Apurimac, considered her a usurper and persona non grata, thus initiating the protest in the central region of Peru.

Andean women marching against the criminalization and terrifying of peaceful protests in the Andean South.

Immediately after the protest, the first social costs began: campesinos with huaracas (handmade weapons) against the National Police and the Army. The disproportion of forces was evident, and the pellets and tear gas bombs, shown in homemade videos, communicated to the other regions that their struggle was the struggle of all. In this first protest there were a total of 28 victims: 10 in Ayacucho, 6 in Apurimac, 3 in Junin, 3 in Arequipa, 3 in La Libertad, and 3 in Cusco. Clearly, the new president’s assumption of power was already stained with the blood of the people.

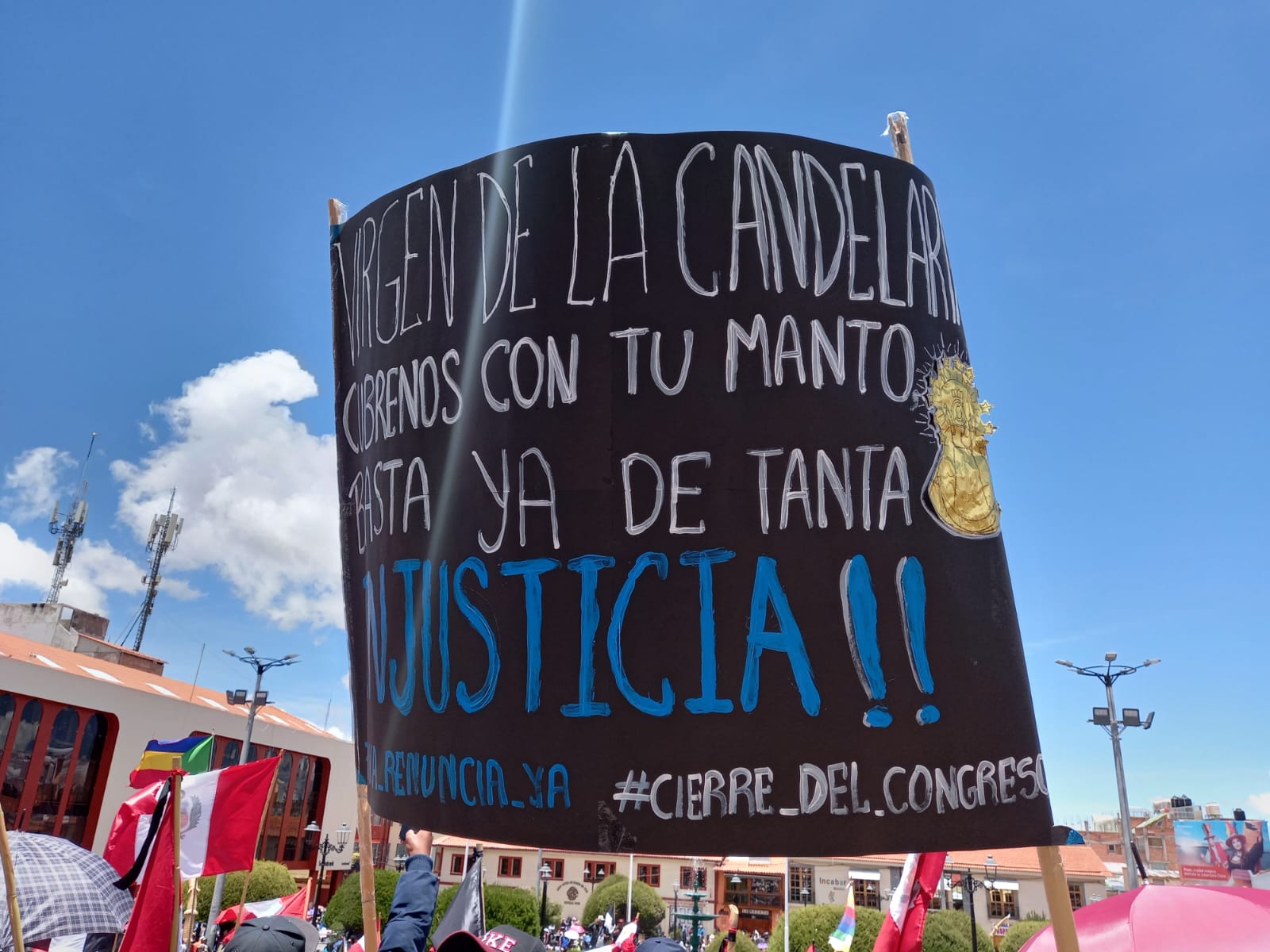

A temporary truce was called after the human losses in the center of Peru. The natal and birth festivities of the son of god gave an air of peace to all that had happened, but a new protest in the southern Andes was now rumored. The lost lives of their brothers could not be left like this, and their dissatisfaction with the person who assumed the presidency was notorious. The community call for peaceful protest in the region of Puno was urgent. Puno, together with the Ayamaras communities and grassroots social organizations, and Juliaca with Quechua communities and campesino patrols, traveled in self-financed caravans to these central cities of the southern region.

The gathering and march were peaceful, but there was absolute silence from the capital’s press, which did not give substantial coverage or visibility to the protests, and rather focused its interest and attention on a president of the Republic who ignored and disregarded reality, holding a phantasmagoric national consultation meeting that was broadcast nationally. This turned what was a peaceful mobilization into a thunderous chaos that pitted civil society on one side against the police and armed forces on the other. The scene became uncontrollable. Helicopters were dropping tear gas bombs and shooting at the population left and right, whether they were protesters or not. The result was 19 people dead, and the only statement made by the executive body was to say, without much remorse, that it was necessary to bring order and control in the country.

A few days have passed and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has issued a pronouncement specifying the disproportionality and illegality of the force used against the demonstrators. They also urged the creation of a negotiation table that includes the intercultural element and respect for ethnically differentiated populations to help in the reparation and reconciliation of the country. Still, the protests continue at the national level; in fact, a goal has been set to reach the capital under the banner of "the taking of Lima."

The caravans of people that move and mobilize towards the capital have not ceased, and the activation of an institution called Ayni to raise funds and everything necessary to travel has begun throughout the Andean region, even extending to the capital, which reflects the validity of the Andean tradition. Institutions of higher learning such as the National University of San Marcos and the National University of Engineering have provided their facilities as a shelter for the protesters from the interior of Peru. Together, they are already preparing for the peaceful demonstrations in the coming days.

On the morning of January 21, police personnel used war tanks to knock down door 3 of the National University of San Marcos, violating all kinds of autonomy that these institutions could have according to internal legal framework. Among the foundations of such arbitrariness were the action of the police, together with a requirement by the dean, for an apparent “violent occupation of the university and theft by the protesters.” This argument was later denied and even renounced by some university authorities as the supreme authority of the university allowed and silenced vile deeds. The result of this intervention was 200 people arbitrarily detained, among whom was a mother with her youngest daughter and student residents of the university itself, which triggered the discontent and total rejection of these persecutory measures that are seen as strategically timed repression of constitutionally legal protests.

Some days after the university incident, during the marches in the center of the city near the facilities of Los Palacios de Power, a new confrontation took place resulting in the first death in the capital. It was Victor Santisteban Yacsavilca, age 55, who, during the demonstration, was killed by a projectile weapon that entered behind his ear and generated severe head trauma—information that was unsuccessfully manipulated through the argument that it was only a blunt blow and that it could have been an injury caused by a fellow protester. These fallacies were debunked by a video broadcast live on Channel N, where the death of Victor was seen in real time.

For its part, the executive body has not given its arm to twist. On the one hand, the president has come out to apologize forcefully while strategically positioning herself as the victim, while on the other hand, the declarations of the premier, Alberto Otárola, using confrontational language, indicate that the president will not resign, and that the demonstrators are terrorists financed by drug trafficking and illegal mining. He also asserted the false interference of the plurinational state of Bolivia and Aymara militia, the red ponchos (a community Bolivian Aymara organization), which has ignited more popular sentiment, and who fearlessly invoke the call to death under the locution, "mom, dad, brothers and sisters, I went out to defend my homeland; if I do not return, it is because I went with her."

Farewell between relatives who traveled to the capital in the demonstration called “la Toma de Lima”.

On the other side, the Congress of the Republic has taken advantage of the situation to present and approve some bills in record time and table others that are of popular interest and public necessity, in addition to demonstrating its intention to cling to power and assert its claim to stay until 2026. These actions are provoking the masses, and at the same time affirming the disconnect and illegitimacy between the constituent and the constituted.

Among the questionable legislation is the constitutional reform law presented by Congresswoman Patricia Juarez of the Fujimorista party, which reestablishes bicameralism in the Congress of the Republic, and whose package, in addition to the return of deputies and senators, proposes to modify 50 articles and add two new ones. This act confirms the condition and quality of the constituent Congress so denied to the national population in its petition for a constituent assembly.

Other worrisome modifications are the direct election of the Comptroller of the Republic by the Congress, omitting the participation of the executive body. Legislative modification that makes possible the removal of members of the National Jury of Elections, National Office of Electoral Processes, and National Registry of Identification and Civil Status by the Congress of the Republic is also proposed. The elimination of the vote of confidence was approved after the installation of a new ministerial cabinet, which would make it impossible to activate the constitutional mechanism attributed to the executive body to debate the general policy of the government and the main measures required for its management, as required by Article 130 of the constitution.

Another legislative proposal was put forward by Congressman Jorge Montoya Manrique of Renovación Popular, who has presented a bill that modifies Legislative Decree No. 1186 regulating the use of force by the National Police. This neutralizes the disproportionality of force in the medium and long term, but for the purposes of the current situation, it is meant to intimidate protestors. In addition, there are other law attempts which aim to shield police officers who participated in the murders, through an amnesty sketched by the party Avanza País.

Another legislative setback is the claim to dismantle higher public education through the deactivation of the National Superintendents of University Higher Education and the return of the National Assembly of Rectors, Congressional Counter Reformation, which means the lapse of university quality, the commercialization of education, and the supremacy of Chicha education (informal education and of poor quality).

Protest posters demanding justice for the 19 murders that occurred in the January 9 demonstration in Juliaca-Peru.

Regarding Native Peoples, new proposals and projects of this government have arisen. Such is the case of Law 3518/2022-CR that intends to modify the "PIACI Law," which protects uncontacted Indigenous or Native Peoples in situations of isolation in Peru. Under an apparent decentralization and delegation of functions and contrary to the initial legislative intent, the modification would allow regional governments to interfere in the recognition of their existence, categorization, and extinction of these Peoples through the “minimum” multisectoral evaluation of nine members made up only of regional representatives, under the ruling of ordinances, and no more, by supreme decrees, as it has been done since its national evaluation jointly with the Ministry of Culture.

Together with the previous project, in the same way an attempt is being made to modify Law 29763 (forest law and wildlife), in which the attempt to add transitory provisions is intended to modify the rules of forest zoning, the delivery of enabling titles in forests, and the requirements for change of land use without further evaluation. These actions clearly highlight the best interest of granting the free hand of the market and continuing to grant permits for deforestation, extraction, and illegal exploitation of the Peruvian Amazon.

Other, no less concerning legislative initiatives, such as those that sought to legitimately paramilitarize campesino communities through the recognition of ‘self-defense’ committees in delegitimization of the systems of internal communal justice, and others that are not documented, but are similarly against the peoples, are the causes of this crisis and its impossible solution to date. The Peruvian state must support and promote the self-determination of the Indigenous Peoples and prevent the normalization of violence against them, giving coverage to their agenda (which they have called the Indigenous agenda) and the fight for political representation. The current fight of the Indigenous Peoples in Peru seeks the creation of the registry of towns in the national system of public records, the titling of property of towns without a clause of transfer of use, the inclusion of a quota of 30 percent representation of Indigenous and Afro-Peruvian peoples, and the decriminalization and ceasing of persecution of Indigenous Peoples, community members, ronderos, and the constituent assembly.

We have to understand that laws against the interests of the historically minoritized majorities will not help to bring the cohesion or social peace that Peru so badly needs. Dialogue and reconciliation of the peoples and the national state must be appealed to, for which the first step is to see diversity as a possibility, rather than a setback.

-- Cliver Ccahuanihancco Arque (Quechua) is Keepers of the Earth Program Assistant. Cliver was born in the Andean region of Peru. He studied Law and Anthropology and holds a specialization in human rights and a Master’s degree in Latin American Studies. He is currently finishing his doctorate in Social Anthropology at the University of Rio Grande do Norte-Brazil.

Top photo: Peaceful concentration of protesters in the main square of Puno in rejection of Dina Boluarte and Prime Minister Alberto Otárola.

All photos by Ronald Callacondo Mollo.