I write as a Mashpee Wampanoag. It is who I am and inevitably shapes my views. The Wampanoag have the distinction of being among the “first contact” Tribes in the Americas, and as such we have a four-centuries-old tradition of interacting with the forces of colonization. This means we have four centuries of grievances, but also four centuries of solutions based on experience. We have seen time and again that the promises of “forever” rarely last more than 30 years. We have seen that when the powers of colonization seek to commodify a resource, they often do so one small piece at a time; what they don't take this year, they will take in 30 years' time.

In April 2023, the world saw the Biden administration commit a full betrayal of its campaign promise to put an end to oil drilling on federal lands. The approval of the Willow Project on Alaska's northern slope will be a devastating blow to efforts to mitigate climate change that we already see unfolding before our eyes. This decision will hamstring any hopes of reaching the stated goals of carbon reduction and keeping global warming below the 1.5º C target. Even these stated goals fall short of the needs of a livable planet for the future of mankind; acceptable losses include millions of human lives that will be displaced at best, or lost at worst. Vice President Kamala Harris defended the decision on a late-night talk show in these words: "I think the concerns are based on what we should all be concerned about. But the solutions have to be, and include, what we are doing in terms of going forward in terms of investments."

This is the inseparable root of colonization: separation from the natural world, commodification, and resource extraction to enrich the few of the investor class. Moving forward in terms of investments. Making money for the ruling class. The royal charter for the Plymouth Colony, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Virginia, or any of the others are charters of incorporation. Colonies are corporations established to conduct trade and profit from land acquisition and resource extraction for the benefit of the investor class. The same is still true today. When we talk about globalization and neo-colonialism with multinational corporations acting outside the local laws, we must remember this has always been the standard mode of operations, from the Dutch East India Company to the Hudson Bay Company to Coca-Cola or Chevron.

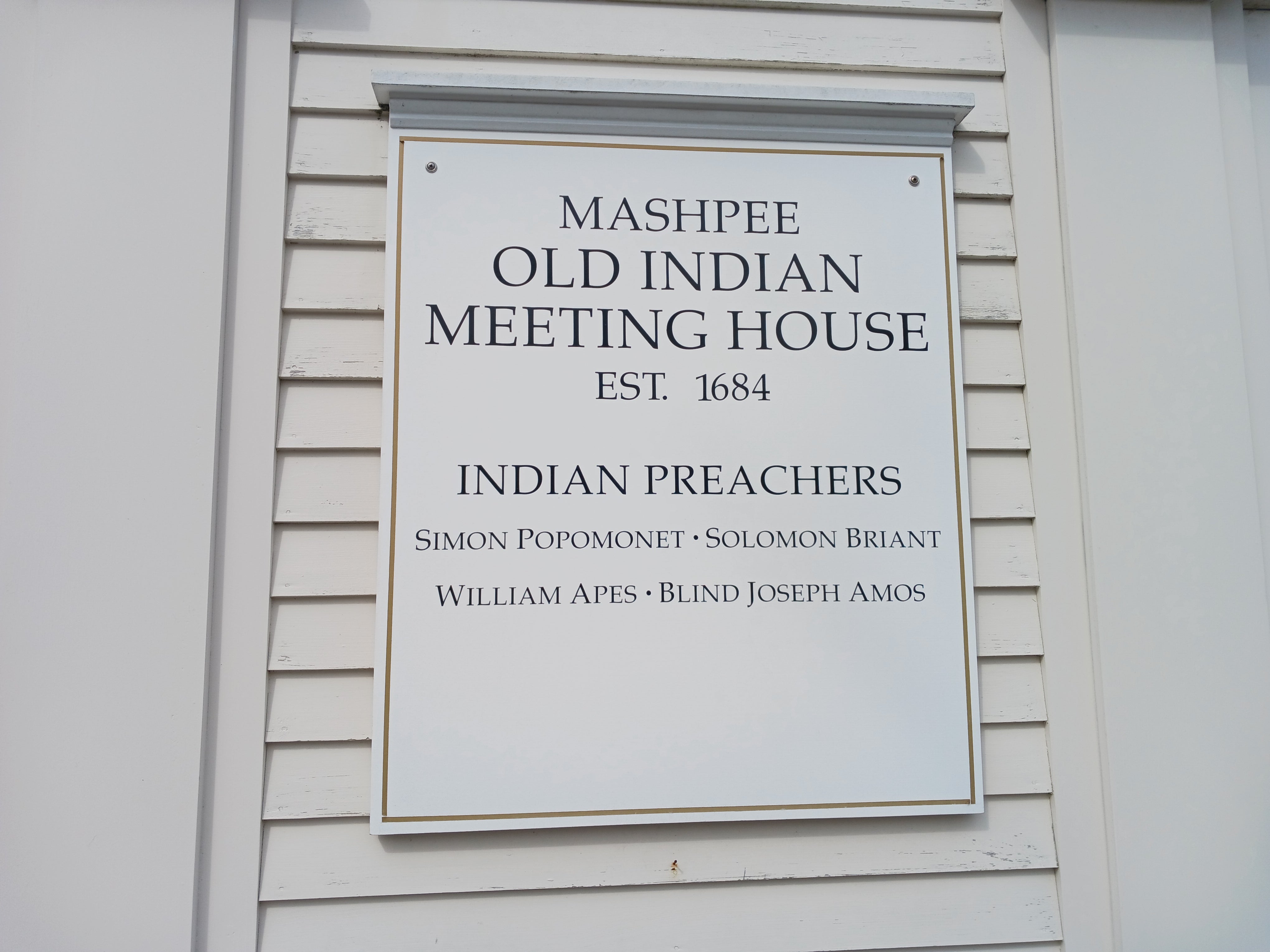

Mashpee meeting house, framed with timber cut from a sacred council oak in 1684. It is the oldest Christian meeting house. The oak beams of this building have witnessed 500 years or more of Wampanoag history.

Today's resource of the empire is oil. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, it was timber. Timber built the British Navy's might that dominated the oceans. Much of the timber that fueled that naval growth was sourced from the eastern woodlands of North America. The majority of the old-growth forests had been clear-cut throughout what we now call New England in the first hundred years of colonization. For the Wampanoag Peoples, our resistance began in the courts, seeking justice under the terms of English law. When that failed, the Tribe turned to open warfare.

Losing that war brought the Wampanoag under the rule of the English crown, and the resources of our lives and our lands were turned over to the local church parish for the “benefit” of the Indians. As the years moved forward, so did the attitude of “moving forward in terms of investments,” and soon the white minister Phineas Fish began to lease off timber rights of Wampanoag lands to the white citizens of neighboring Sandwich in order to line his own pockets.

In response to these actions, the Wampanoag people in Mashpee came together to leverage their legal rights, not as a Tribe—because Tribes had very little in the way of rights—but as Christians. That the church was established to propagate the faith among the Indians gave the Mashpee Tribe a distinct advantage. While Phineas Fish preached to an all-white congregation within the meeting house, a Wampanoag minister, Blind Joe Amos, ministered to the Wampanoag under a giant oak tree. In 1833 Amos was joined by the radical Pequot minister William Apess, and together they proceeded to create a provocative plan for legal challenges paired with direct action to bring the issue to a head.

Mashpee Meeting House.

The first step was to write out a declaration of independence for the Mashpee Wampanoag. Its opening lines read: “We say in the voice of one man that we are distressed and degraded daily by those men who we understand were appointed by your honors. That they have the rule of everything. That we are not consulted, it is true, and if we are, they do as they please and if we say one word then we are called poor drunken Indians when in fact we are not….All of our privileges are in a measure taken from us. Our people are forsaken—many of them sleep upon the cold ground and we know not why it should be so, when we have enough if properly managed to supply all our wants.”

The declaration issued three resolutions:

“Resolved

That we as a Tribe will rule ourselves, and have the right to do so for all men are born free and Equal, says the constitution of the country.Resolved

That we will not permit any white man to come upon our plantation to cut or carry off wood or hay or any other article, without our permission after the first of July next.Resolved

That we will put said resolution in force after the date of July next with the penalty of binding and throwing them off the plantation if they will not stay away without.Yours most obediently as the voice of one man we approve the above as the voice of one man we pray you hear.”

The document was signed by 108 Tribal members and submitted to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on May 21, 1833.

The original protest of Martin Luther posted to the cathedral door demanding that the people would be preached to in their mother tongue was leveraged to unseat Fish and replace him with Amos; Amos had won fame for memorizing the bible in both English and Wampanoag, allowing him to minister to his flock in their own tongue.

Mashpee Meeting House.

Taking direct action on the first of July, the Mashpee Tribe began enforcement of the declaration, halting a party of woodcutters by seizing their carts, saws, and axes, binding the men, and removing them to the town line. For these direct actions against the encroachment on their resources, William Apess and a number of Tribal members were arrested and convicted. Apess spent 30 days in the Barnstable House of Corrections. While serving his sentence, Apess wrote a letter that would appeal to the freedoms espoused in the constitution and the Christian virtues laid out in the bible. Echoes of this letter can be found 30 years later in the words of abolitionist Frederick Douglas, and 130 years later in a letter written from a jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama, by Martin Luther King Jr.

Apess’ letter, addressed to the Massachusetts House and Senate, opens: “Where it is expected, by the inhabitants of this commonwealth, that justice and equality will ren in the hearts of all - that national prejudices and peculiar feelings, attending religionists, will not be permitted to rule in the hearts of any - but that every enlightened and judicious representative, as we trust they all are that compose this body, would be willing to do as they wish to be done by; and we wish this honorable body to consider our oppression.” it goes on to outline a list of grievances and ends with a rousing outcry for justice. “White man! The blood of our fathers spilt in the revolutionary war cries from the ground of our native soil, to break the chains of oppression, and let our children go free!”

The letter was published in a number of newspapers across New England, and the attention that it brought gained Mashpee self-governance, only to see 30 years later that we were forced to incorporate as a town in the Commonwealth against our will. Nearly 200 years later, we are still fighting for this same dignity, to keep what is ours in spite of how it could enrich others who covet our land.

Illegal clear-cutting of about a hundred acres for development in Mashpee brought minimal fines that amount to a slap on the wrist compared to potential profits for developers.

For the colonial mind and the corporate mind, the idea that a resource would be allowed to simply exist without being commodified for profit is unimaginable. From this viewpoint, the only way a community or a nation should be allowed to control a resource is if it is leveraging it for profit. To the invested interests there is no value in natural beauty, fresh air, clean water, or in preserving a livable planet for the future. The only value is the here and now of quarterly earnings and profit statements.

Whether it is oil in Alaska, lithium in Peru, diamonds in Angola, or real estate development in Mashpee, we must stand ready in each generation to challenge the greed and injustice of the insatiable colonial machine. Our very survival depends on it.

--Hartman Deetz (Mashpee Wampanoag) has been active in environmental and cultural stewardship for over 20 years. He is a traditional artist as well as a singer and dancer, having shown his art in galleries, and performed for audiences from coast to coast across the US. He is currently a 2023-2024 Cultural Survival Writer in Residence.

All photos by Hartman Deetz. Top photo: Mashpee River. Some of the last pristine sections of Mashpee River are under pressure for development. Developers of the Mashpee Commons promise "affordable housing" but a recent study found that only 2% of housing listed as affordable for tax and zoning purposes was actually listed as "below market rate" (WGBH priced out).