The extractivist growth model for transition minerals has emerged in Latin America in recent years, fueled by a sharp spike in demand for batteries and other technologies for the transition to the so-called “green economy” by industrialized countries and rising superpowers alike. This demand for transition minerals reflects a new economic and political ideological order connected with the green economy, which has resulted in new socio-environmental and cultural impacts. The demand for resources and raw materials from the global south is the same as that which developed and enriched the global north over the last five centuries, to the detriment and impoverishment of local communities and Indigenous Peoples. This new race for resources has renewed well known conflicts and problems by putting Indigenous Peoples and the environment at risk of human rights abuses and environmental degradation.

The Jequitinhonha Valley in southeast Brazil has been a hotbed for mining for decades, with new destructive transition mineral extractivist activities instigating even more conflicts, anxiety, and rights violations in Indigenous communities. The territories of Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities like Quilombolas are deeply impacted as a result of the large mining companies' intensification of operations and expansion of production. Extractivist projects are simultaneously undermining rights and weakening States that have the responsibility, under national and international laws, to respect, protect, and fulfill Indigenous rights and the security of local communities.

The Jequitinhonha Valley in Minas Gerais has been exploited for iron, gold, and precious gems for centuries. Despite its natural riches, this area is one of the most impoverished regions, severely affected by economic and social struggles. The recent discovery of significant lithium deposits there established Brazil on the transition minerals map for good, adding Brazil, along with Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, as one of the largest lithium sources in the world. Sigma Lithium Resources, a Canadian company that has the biggest mining presence in the region, claims that its operations are “sustainable.'' In reality, their actions are creating hardship and destruction for Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities affected by their activities.

It is evident that the process of historical and geographical colonization in the region, along with ongoing conflicts related to the mineral industry and agribusiness, has been working to delay Indigenous land demarcation for years. The influx of major mining companies, speculation for mining licenses, and the subsequent rise in land prices also contribute to making the local people’s lives difficult. Studies show that between 1970-1999, there were 541 registered mining titles; this number increased almost 10-fold to 5,068 titles between 2000-2018, with mining operations now occupying a vast area totaling 37,000 square kilometers. Starting in 2018, Brazil’s government suspended all demarcation for Indigenous lands and granted mining licenses, increasing exponentially the influx of pernicious mining operations in the region.

This satellite image from Mapbox shows the coverage area, routes, and impact of Sigma Lithium Resources and other mining companies in the region. The following landmarks are numbered:

- Cinta Vermelha Indigenous land, home to the Pataxo, Cinta Vermelha, Pankararu, and other semi-nomadic Peoples, such as the Maxacali, who live in the area, and the municipality of Itira, where other mining corporations are operating.

- The Araçuaí River, which is already discolored due to intense mining activities in the region. This river supplies the city as well as numerous local communities along its banks.

- The Jequitinhonha River, sacred to the Pataxo, Cinta Vermelha, and Pankararz Peoples who live there, is under imminent risk of contamination, posing losses, damages, and risks to the lives of these and Quilombola communities.

- One of Sigma's mines in the region.

Jequitinhonha Valley: Home to Indigenous and Quilombola Communities

According to Cleonice Pankararu (Pankararu), a local Indigenous leader, and Geralda Alves, a dedicated researcher of Indigenous Peoples in the region for decades, several Indigenous communities are directly affected by the mining activities. In addition to the Krenak Peoples, who number around 600, there are approximately 900 Maxakali Indigenous people who are experiencing disruptions to their nomadic lifeways near the Jequitinhonha River and other locations. The Aranã Peoples, who are reclaiming their identity and territories, reside a mere 300 meters away from a mining site. The Tupinikim/Guarani Peoples living in the northern part of the valley depend on the ecological systems of the region. The remaining Pataxo and Pankararu communities in the area have chosen to stay and safeguard their traditional territories. The Aranã, Pankararu, and Pataxó Peoples are the ancestral inhabitants of the Jequitinhonha Valley.

According to data from the Palmares Foundation, a State agency serving Black communities, the Jequitinhonha Valley has one of the largest densities of Quilombola communities in Brazil, with 95 recognized traditional communities to date. Indigenous representatives such as Geralda Chaves Borum, say that there is no State presence or any policy to protect Indigenous Peoples in the Jequitinhonha Valley: “There is no FUNAI or any service to support these communities. Right now, 18 members of a nomadic Indigenous group have arrived at my house, with no State support. With the mining, the situation is even worse.”

The Dynamics of Negotiation and Oppression: A Letter of Indignation to Sigma Lithium Corp

The struggle for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and affected local communities will only succeed when they become the protagonists in the defense, reparation, and protection of their lands. This requires that the State apparatus, corporate entities, and scientific community reflect upon and integrate the knowledge of the people that historically have been invisible. In the region, it is not only the State and corporations that undermine these communities, but also local academic institutions that align themselves with large mining companies.

Judicial decisions regarding mining-related disasters in the area should prioritize local, traditional, and environmental knowledge that has been forged through the struggle for rights, self-determination, and a healthy environment. Sociologist B.S. Santos once said that "global social injustice is closely tied to global cognitive injustice," thus emphasizing the need to fight for both types of justice on a global scale. It is crucial to shed light on this battle and question the assumptions underlying this new economic paradigm.

In Brazil, there is an extensive legal framework that governs the mining sector. Mining companies must conduct thorough research to identify and acquire the appropriate mining rights, concessions, or leases for the desired mineral deposits. However, these processes have been relaxed and even suspended by governments to cater to the powerful lobbying efforts of corporations and foreign governments.

Opening a mining operation involves several political and legal actions:

1. Obtaining a mining concession through the National Mining Agency.

2. Environmental licensing. Mining projects in Brazil require Environmental Impact Assessments to obtain an environmental license. These assessments must be issued by a neutral third party that evaluates potential environmental and social impacts and ensures compliance with environmental regulations.

3. Respecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. If the mining project impacts Indigenous territories or local communities, obtaining the Free, Prior and Informed Consent from these groups is necessary. Brazil is a signatory of ILO Convention 169 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and has specific laws protecting Indigenous rights. Engaging in a transparent, meaningful consultation that respects self-determination, under community protocols, with Indigenous and local communities, is crucial.

4. Engaging stakeholders. Building positive relationships with local communities, governments, and other stakeholders is essential. This involves communication, transparency, and addressing social and environmental concerns. The company should respect national and international laws and not be involved in corruption or unfair and illegal lobbying in order to bend laws. Frequently, big corporations cut deals to elude laws and regulations and carry out illicit efforts to influence decisions in their favor. (See: Glencore agrees to make a payment of up to $1.5 billion in order to resolve allegations of corruption in Latin America.)

The local communities, Indigenous Peoples, and Quilombolas from the Jequitinhonha Valley residing in the affected lands assert their strong opposition to Sigma Corporation's presence and activities. They believe that the company unduly influenced the government and neglected to fulfill necessary due diligence, failing to comply fully with the actions cited above, especially related to their Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Sigma received an operating license in March 2023 in Minas Gerais to sell and export lithium for the production of electric vehicle batteries. The company received the license despite violating the rights of local populations by failing to obtain their Free, Prior and Informed Consent. The Public Ministry and local Quilombola organizations had recommended further studies before the start of mining activities, as the region has more than 130 cataloged water sources and is considered the reservoir for the municipality of Araçuaí. However, Sigma started its mapping and earthmoving operations in 2020, years before obtaining a license.

Minas Gerais state/Wikipedia

Sigma's proposal heralds "green and sustainable mining," but their lithium extraction activities have been negatively impacting Indigenous territories and environmental protection reserves. Sigma Co-CEO, Ana Gardner, recently stated that the complex called Grota do Cirilo, which is being implemented in two phases in the municipalities of Itinga and Araçuaí, will produce 440,000 tons of high purity lithium concentrate per year. This activity will directly impact the access to water for residents of local cities and towns. Rural communities in the Jequitinhonha Valley have a 16,000-liter capacity water tank for domestic consumption for 8 months, which translates to 2,000 liters per family per month. Meanwhile, the National Water Agency granted Sigma 3.8 million liters per day (100 million liters per month), which would be enough to supply 34,000 families. Sigma estimates its production will gradually increase in the coming months and reach an annual production rate of 270,000 tons of spodumene concentrate (the mineral source of lithium) by July 2023. This will worsen the situation of local communities.

Community members in the Jequitinhonha Valley are standing united in their determination to safeguard their rights and protect their cherished land from any further encroachment by saying “no” to the mining operations. In July 2022, a collective of traditional and Indigenous communities sent a letter of protest in which they listed the problems and the causes of these problems in the region. The letter states:

“We denounce agro and no longer tolerate and hydrobusiness, hydroelectric dams, eucalyptus monoculture companies, and mining companies that: open prospecting holes and leave the craters of greed in our soil, imprison and kill our rivers, steal our plateaus and dry up all our fountains of life; who invade our territories and spray poisons, contaminating our Mother Earth and our people, saying that they are the owners. That is why we cry out in one voice: landowners and land grabbers out, SAM, out! Sigma, out! RIMA, out! NORFLOR, out! Monte Fresno, out! Rio Rancho, out! ArcelorMittal, out! APERAM, out! SUZANO, out! Veracel Celulose and Votorantim Metals, out! TTG Brasil, out! Tomasini, out! Floresta Minas, out! UHE de Formoso, out! Coagro, out! IROBRAS, out! Minas Liga, out! UNIÃO, out! CBL, out! Gerdau, out! Replasa, out! CBA and all other violators of rights, out! We demand them to cease offering mining training and all related fields of study at the IFNMG Campus of Araçuaí College; Governor Zema, out! Get out! Leave!”

Jequitnhonha Valley - Wikipedia

When communities organize this type of protest, they do so based on their own historical experience with mining in the region. We know how unchecked capitalism, colonialism, and the logic of new economies operate. Sigma’s environmental and human rights policies as published in newspapers promise programs to distribute food and prevent diseases as well as offer education in mining. In other words, the company wants to transform the dynamics of dependence and local governance by creating a system of oppression and misery, as communities that have lived off the land in freedom, producing their own subsistence and experiences, must now prepare to receive food and treatment from an invading company.

This capitalist and colonial dynamic transforms the environment and common goods into commodities and offsets in global chains controlled by large corporations, creating injustice, hunger, and destruction. When we see how the State is aligned with Sigma, we remember the other giant in mining and champion in the destruction of the environment, Companhia Vale do Rio Doce Corporation, today called Vale, which also operates in Minas Gerais, was created as a State-owned company under an authoritarian regime in the context of the Second World War. Through a three-way contract between the United States, England, and Brazil, on March 3, 1942, Vale began to supply raw materials to the military industry globally.

The Political and Judiciary Lobby Against the Peoples: Ways to Erase Memory and the Environment

In May 2023, the governor of Minas Gerais, Romeu Zema, traveled to New York to launch the "Lithium Valley" on the NASDAQ stock exchange. Governor Zema has been promoting this program, along with political figures and judges from the judiciary, as the "economic and social salvation for the Jequitinhonha Valley." He is seen as the biggest lobbyist for those industries and an enemy of Indigenous Peoples.

Photo shared by Governor Zema promoting the Lithium Valley at the Nasdaq in New York.

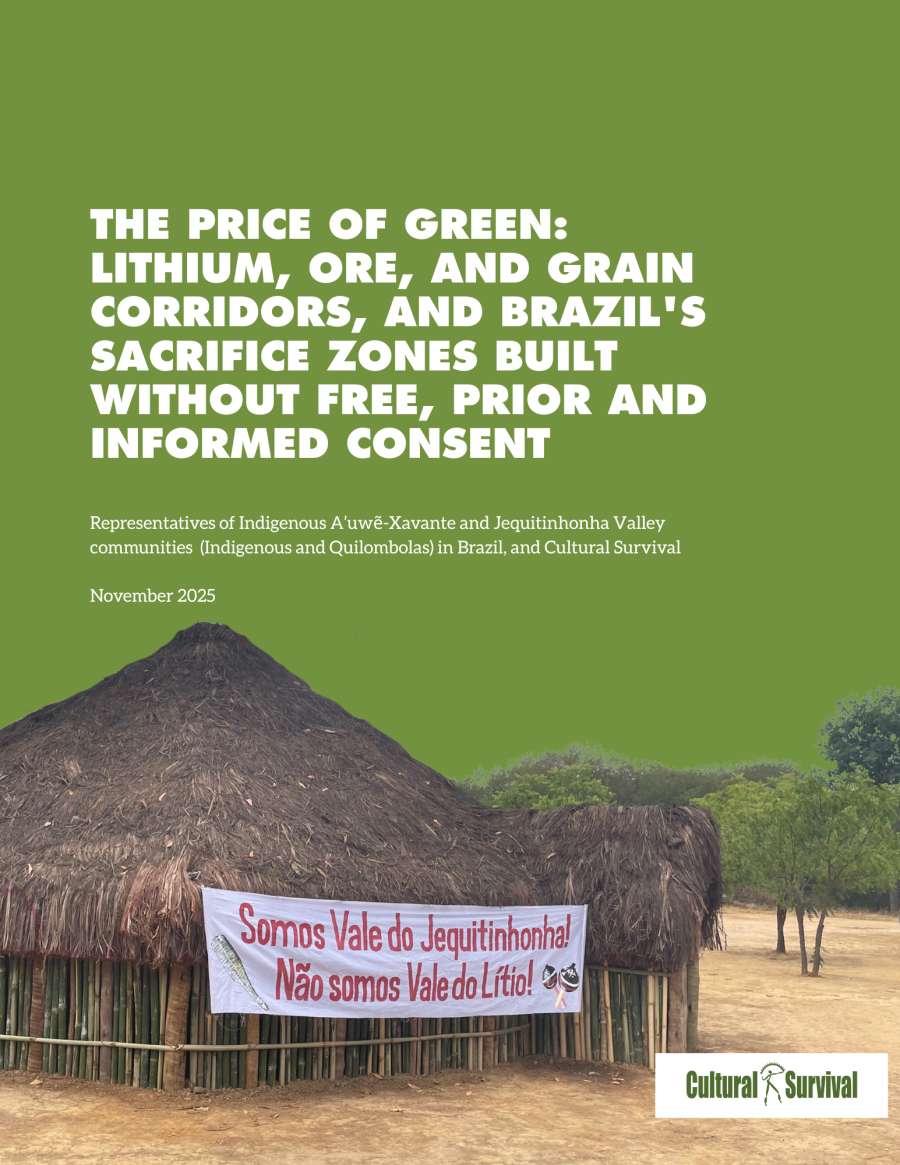

According to the local collective of Jequitinhonha Peoples, the name "Lithium Valley" has been dominated by Canadian companies, particularly Sigma Lithium Resources, which started producing what they call "green lithium" in May. “They are trying to rename the area and destroy our memory,” says one member of the community. By using the word “green,” the companies are claiming that the resources are extracted in an environmentally and socially responsible manner—but this is not supported by reality.

The Lithium Valley project will impact 14 municipalities in the Jequitinhonha Valley, Mucuri Valley, and the northern and northeastern regions of Minas Gerais, which include Araçuaí, Capelinha, Coronel Murta, Itaobim, Itinga, Malacacheta, Medina, Minas Novas, Pedra Azul, Virgem da Lapa, Teófilo Otoni, Turmalina, Rubelita, and Salinas. These communities are home to rural, traditional, and Indigenous people.

According to Midia Ninja, an independent Indigenous media outlet on Instagram, Sigma shared its Environmental Impact report of the Grota do Cirilo. The report failed to address Indigenous issues and other environmental issues, but Sigma was nevertheless granted permission to extract 150 cubic meters of water per hour from the Jequitinhonha River, equivalent to five water tanker trucks per hour.

Despite claiming to invest in the region, prioritize sustainability, and protect water sources and human rights, the company and Governor Zema (who sold the government’s 33 percent stake in the Brazilian Lithium Company, which is now 100 percent privately owned) did not provide any safeguards on human rights, environmental protection, or Indigenous consultation. The local communities are claiming that their water streams, essential for their crops, are disappearing and the rivers are contaminated. To this date, no technical study has been conducted to explain the situation.

Sigma’s actions in the Jequitinhonha Valley have raised serious concerns about the company’s disregard for the principles of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent. The company's authorization to extract a significant amount of water from the Jequitinhonha River severely threatens the water access of local communities and Indigenous Peoples and poses perils to the livelihoods and well being of the people who depend on this vital resource. Furthermore, Sigma's activities will lead to the destruction of memorial landscapes and territories, erasing the cultural and historical significance of these areas. Maxacali, Krenak, Arana, and other Indigenous Peoples who currently freely move around the region for ceremonies will be deeply impacted.

The image(source) above shows another mining company in the region Lithium Ionic that, with CBL and Sigma, is operating on Indigenous and Quilombola lands.

Sigma has also demonstrated a lack of respect for the environmental and social values of the region. In a recent Open Letter (read the original here or the English version), collectives and Indigenous communities denounce the violence of the State, judiciary system, and big corporations:

“In addition to mining companies, monoculture eucalyptus plantations and agribusiness have also been responsible for the displacement of many communities. These communities also suffer from land-grabbing processes orchestrated by large landowners and corporations. There is a lack of public policies that guarantee the rights of these Peoples, while there are abundant resources and incentives for large landowners to destroy the environment and our well being. In Minas Gerais, where more than half of Brazil's eucalyptus monoculture is found, over the past decade, our state has recorded the highest number of workers in slave-like conditions. We can no longer tolerate the atrocities committed by the government of Minas Gerais, led by Romeu Zema, in collusion with large corporations and with the complicity of the Judiciary.”

The Jequitinhonha River, Not Lithium, Shapes the Valley

Indigenous and affected communities are demanding the immediate establishment of a task force composed of Indigenous Peoples and members of the local communities, the true guardians and caretakers, to review this project in depth. This task force should focus on thematic studies, mapping the communities and their territories, rights, and the documentation of their extensive cultural repertoire related to management practices, agriculture, food systems, and extractive activities. It is essential to conduct a participatory inventory of their tangible and intangible cultural assets, as well as sites and places of ancestral memory. Furthermore, the establishment of communication and reporting platforms at national and international levels is necessary to address this unacceptable situation of human rights violations and environmental degradation in Minas Gerais. Local collectives also emphasize that the population was not consulted about the project: "We are seeing politicians and businessmen saying what our region needs, but nobody listened to the people." In response, the Public Prosecutor's Office has recommended the nullification of the Sigma Mining Company's research in Araçuaí.

Mining has deeply impacted local communities. The mining model in Minas Gerais has historically been rejected by Indigenous Peoples and by numerous traditional communities because mining has been synonymous with the violent annihilation of the ways of life in these territories. Polluted rivers are unsuitable for fishing, bathing, and rituals, as are the resulting noise pollution and air pollution from mineral waste, which emits a terrible smell, and the noise from machinery and explosions, in addition to the dangerous traffic of huge trucks.

The historical violence associated with mining in the region has reached alarming levels, exacerbated by the interference and rapid expansion of China, as well as the increasing demand for lithium from European countries. While nations such as Germany, Japan, the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and China profit from the mining industry, less economically developed countries bear the burden of its devastating impacts. Tragically, in Brazil, it often takes catastrophic events, such as the Mariana (2015) and Brumadinho (2019) dam failures, which resulted in the destruction of ecosystems and claimed the lives of nearly 300 individuals, for the world to pay attention to the consequences of these mines.

Discussions and consultation processes involving Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the Jequitinhonha Valley, as elsewhere in the global south, have been characterized by an evident power imbalance. Civil society workers find themselves trapped in an unjust economic dependency on the mining industry without any viable alternatives, and the local municipalities suffer greatly due to unfair treatment by the State, which unjustly favors large industries and imposes high living costs on the population.

The Minas Gerais state government, attending to industry lobbyists, wants to change the name of the Jequitinhonha Valley (which, in Indigenous languages, means “long river of fish”), to the Lithium Valley. This valley is so much more than a repository for lithium. The Jequitinhonha is an ecosystem of rivers, plants, communities, animals, birds, and numerous species, not just minerals.

The communities that live near Mineracao also face this war against their cultures and their health. Feeling vulnerable, they suffer from physical and mental pain and deep anxiety for the future. They testify to a loss of historical and cultural references to the land, or the obliteration of the memory of sacred places and the invisibility of the people as more and more mining activities take place. Mining transforms rivers into ecological corpses, and the landscape into a cemetery of species. The extractive industry and the State sell a discourse that life without mining is not possible. Indigenous Peoples can attest that that is surely not the case.

List of Collectives, organizations, Traditional and local communities, and Indigenous Peoples impacted by the Lithium mining in the Jequitinhonha Valley:

- Aldeia Cinta Vermelha-Jundiba

- Pankararu-Pataxó People

- Aldeia Geru Tukunã Pataxó, Açucena

- Apanhadores de Flores Sempre Vivas

- Brazilian Association of those Affected by Large Enterprises (ABA)

- Association of the Paraguai Remanescente Quilombola Community

- Association of United Carters and Carters of Belo Horizonte and Metropolitan Region

- Eloy Ferreira da Silva Documentation Center (CEDEFES)

- Chapadeiros of Lagoão de Araçuaí

- Margarida Alves Popular Advisory Collective (CMA)

- Commission for Popular Advocacy Support of OAB-MG

- Commission for the Defense of the Rights of Extractive Communities (CODECEX)

- Pastoral Land Commission (CPT/MG)

- Quilombola Commission of Alto e Médio Rio Doce

- Guegue Indigenous Community

- Ilha Funda Quilombola Community, Periquito

- Águas Claras Quilombola Community, Virgolândia

- Campinhos Quilombola Community, Congonhas

- Córrego do Narciso Quilombola Community

- Gesteira Quilombola Community

- Pontinha Quilombola Community, Paraopeba

- Araújo Family Quilombola Community

- Mutuca De Cima Quilombola Community, Coronel Murta

- Paraguai Quilombola Community

- Queimadas Quilombola Community, Serro

- Faiscadores Traditional Community, Alto Rio Doce

- Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI)

- Intermunicipal Community Council of the Traditional Geraizeiro Territory of Vale das Cancelas

- Pastoral Fishermen's Council (CPP)

- Federation of Quilombola Communities of Minas Gerais - Ngolo

- National Forum of Traditional Communities and Peoples of Brazil

- Study Group on Environmental Themes (GESTA/UFMG)

- Dom Tomás Balduíno Institute

- Kaipora - Biocultural Studies Laboratory

- Souza Family Kilombo

- Manzo Ngunzo Kaiango - Urban Quilombo Culture Resistance

- Movement of Those Affected by Dams (MAB)

- Landless Workers' Movement (MST)

- Rural Workers' Movement (MTC)

- National Movement of Traditional Fisherwomen and Fisherfolk of Brazil (MPP)

- Movement for Popular Sovereignty in Mining (MAM)

- Women of Areias NGO

- Aranã Caboclo People of Coronel Murta and Araçuaí

- Ancestral Religious Tradition Peoples and Communities of African Matrix (PCTRAMA)

- Vargem do Inhaí Quilombo

- Baú Quilombo, Araçuaí

- Root Quilombo

- Quilombola Network of the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte

- National Network of Popular Lawyers (RENAP)

- Land of Rights

- Kamakã-Mongoió Indigenous Land, Brumadinho

- Xakriabá Indigenous Territory

- Brejo dos Crioulos Quilombola Territory

Top photo: Valley of the Jequitinhonha / Caatinga - Vale do Jequitinhonha. Photo by A. Duarte.