Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, if I wanted to peer into my history, I did not visit a museum. Accessing the world of my ancestors meant putting my rain gear on, taking a boat to an old Haida village site, and seeing the places where my people lived and thrived since time immemorial. It meant visiting abandoned fishing villages filled with old totem poles melting into the moss and holes where longhouses used to be, there would also be violent, fresher holes in the ground, making the places where totem poles had been cut down and carted off to museums all over the world. This used to make me incredibly upset. I know when a totem pole is erected the prayers that one prays work to bring the pole alive. It seemed a much more noble fate for the pole to slowly return to the earth, eaten by moss and weathered by the wind, until it became a log once more—rather than something artificially preserved in a museum in an alien context.

This past spring, I visited the American Museum of Natural History in New York to see the new Northwest Coast wing created in consultation with my Nation, as well as the Coast Salish, Gitxsan, Haíltzaqv, Kwakwaka'wakw, Nisg̱a’a, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nuxalk, Tlingit, and Tsimshian Nations. From my parents, I knew that most museums with Haida pieces in their collections, a couple of emails to the right people would permit you access to the back rooms and to collections that are not on public display. This, of course, is what I did.

I got my visiting researcher badge and waited before meeting the sweetest woman who would be showing me around the collections. When she greeted me, I had the surreal feeling of meeting an old family friend for the first time. Through the years, she had given similar tours to my father, mother, uncles, and aunties. She asked me about my cousin who had just had a baby and she was surprisingly caught up on the goings-on of Haida Gwaii.

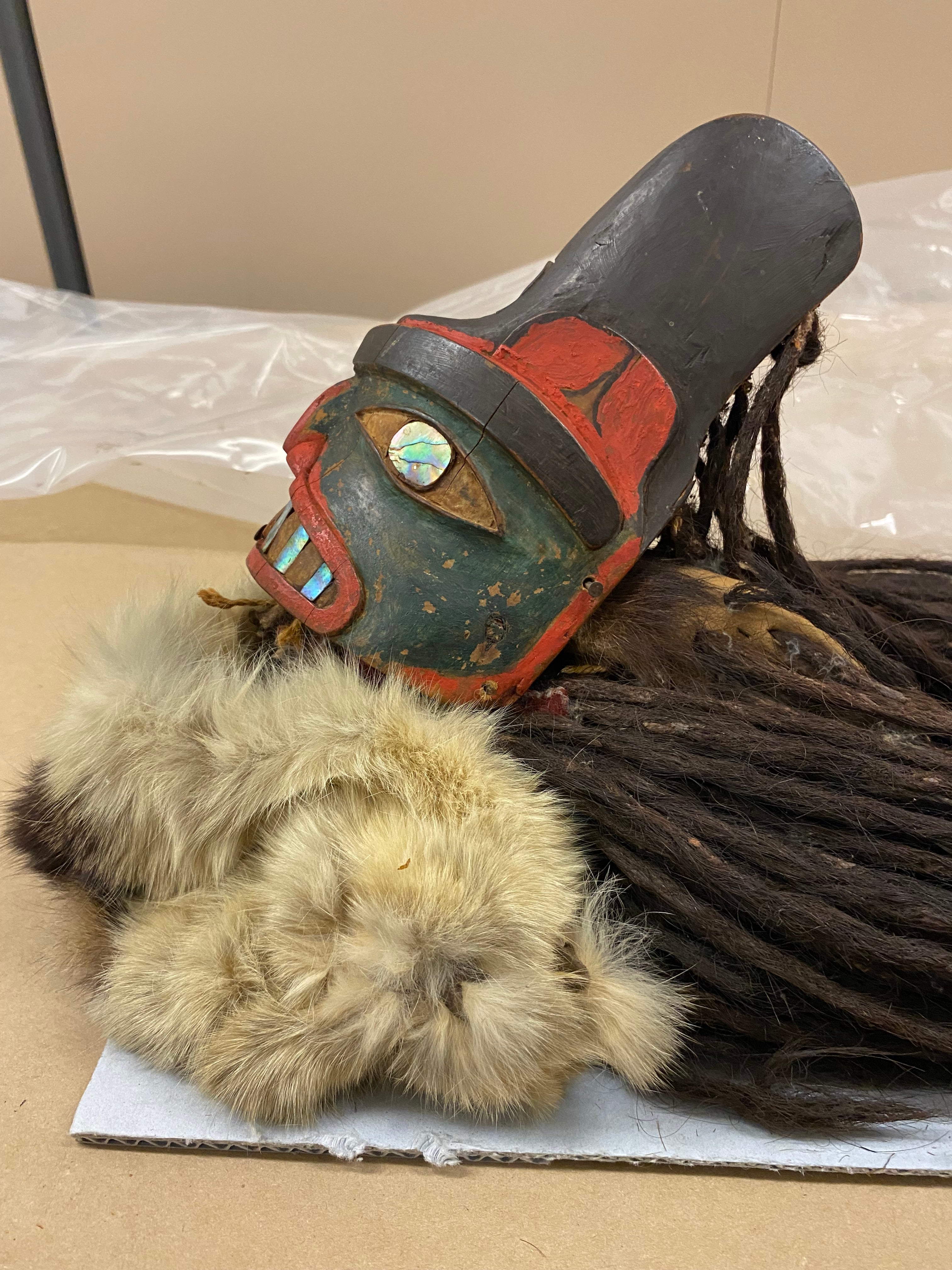

We entered the climate-controlled rooms holding the Haida collection. There, we put on gloves and were allowed to inspect the Haida masks, regalia, carved dishware, toys, and boxes at leisure. The lady told me that gloves are necessary because the museum's old practice employed for pest control was to essentially chemically bomb our artifacts and to this day they are not safe to be around for an extended time. Many institutions employed this method, which means that even when communities do repatriate artifacts, the treasures often cannot go back into use safely. These artifacts were made to be used, but their exposure to dangerous chemicals means that something that was once purely good now has been made dangerous. It also means that the artifacts have different storage needs, putting a higher cost upon Indigenous communities to ensure they have adequate storage capabilities whilst repatriating their belongings.

With each object we encountered, I had questions and wanted to know the story of what I was holding, how it came to be in the museum, and what it was used for before. There was a dark mask with bear hair eyebrows, apparently a death mask, and there was a white doll with abalone eyes and no explanation. We had access to an online database with the field notes from whichever anthropologist retrieved the item. However, most of the time, these were deeply underwhelming. Sometimes they were only one or two-word attributions, sometimes they were nonsensical.

Growing up, I'd see my father spend hours at his computer, analyzing images of museum artifacts to prove whether a misattribution had occurred. These things are difficult to prove, but it is a form of respect to these artifacts to find their proper Nation of origin and artist, if possible.

In the United States, repatriation laws are pretty straightforward, thanks to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) which was enacted in 1990. NAGPRA makes repatriation standardized. As with any law, its implementation is often a challenge. This legislation was made to grapple with the tension of museums as places that preserve the past and the fact that cultural items belong with the people they were taken from. Things become more complicated with international repatriation, which is not regulated, but NAGPRA functions as a sort of blueprint. International repatriation does happen, it is more complicated.

Repatriation is not the only way for us to reclaim our past. Taking our cultural artifacts without our consent is not the full extent of the theft that museums partake in. Chemically bombing our objects and artifacts and making them unsafe for use is another form of theft. To misattribute artifacts to different Nations is yet another theft, a theft of legacy. So ensuring good relations with a museum does not always mean getting everything back. It can mean being in control of how we are perceived; ensuring that the stories that outsiders tell or are told about our culture come from our culture and are accurate. Cultural revitalization looks like the new wing in the American Museum of Natural History, a place where there are videos of our Elders discussing our home, a place where the beauty of our past is shared alongside depictions of our living and growing culture.

After exploring the off-display collection, I visited the new public display. In this exhibit, I saw a video of my relatives speaking about our art and our land. Being homesick, I watched it three times. As visitors cycled past, including a seemingly ceaseless amount of school groups, I thought about the access that all these young people had to my culture that my people gave them.

Beyond the uses of the artifacts, the art and carving displayed on them tells a story, and when museums listen to and work with Indigenous Nations, those stories are able to be told by people to whom they are legible. I thought of all the other Native youth who will see this exhibit and feel the pride I feel that our work is being shown with our consent and honored to the utmost extent.

--Haana Edenshaw is a member of the Tsiits Gitanee clan of the Haida Nation. She grew up on Haida Gwaii learning from her Elders and her land. She is a second-year student at Deep Springs College in California. She has been an environmental justice and Indigenous rights activist for much of her life and is working on cultural revitalization and language learning. She is one of 15 youth suing the Canadian government for their contributions to the climate crisis. She is also a board member of the Vancouver-based charity Justice For Girls. Haana is a 2023-2024 Cultural Survival Writer in Residence.