While governments continue their linguicidal practices, Indigenous communities around the world are taking charge of their linguistic future with projects designed according to their own values and the level of endangerment of their native languages. In an encouraging speech, Dr. Richard A. Grounds (Yuchi/Seminole), Executive Director of the Yuchi Language Project based in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, urged Indigenous communities to stop being mere witnesses to the loss of speakers of our languages. Instead, he told us, “We must take action, take charge, and overcome inertia.” The speech took place at the Grassroots Indigenous Language Exchange and Convening organized by Cultural Survival in Oaxaca, Mexico, in May 2023. Representatives from several language revitalization projects from communities in Colombia, Russia, Mexico, the United States, and Ecuador took part.

The working groups at the conference were as diverse as the languages they represented. They included everyone from children to Elders, family initiatives to large intercommunity programs; those with small and large budgets; ones with few fluent speakers remaining to those whose entire communities spoke the language; and those who had developed written materials or toys for oral learning. Although their particular situations varied, the participants agreed on several key points: “The policies that protect Indigenous languages only work on paper;” “We are running out of public spaces for our languages;” and “If we do not organize ourselves, the government is not going to do it.” So, they decided to begin at home, in their communities. The dream is a future where babies grow up naturally learning their languages, and that these will be heard in all aspects of life in the community.

Everyone shared the desire and effort to perpetuate their languages and create new speakers despite the difficulties, to overcome inertia and not just be witnesses to their disappearance—but it was also agreed that it is not so easy to overcome inertia. People who want to learn or relearn their Indigenous languages face multiple challenges just to stay motivated in the learning process. In addition, it is not always possible to involve other members of the community, especially if a long-term project is proposed or is one that requires many people. Certain projects have chosen to pay a stipend to language masters and apprentices so they can spend dedicated time strengthening their fluency.

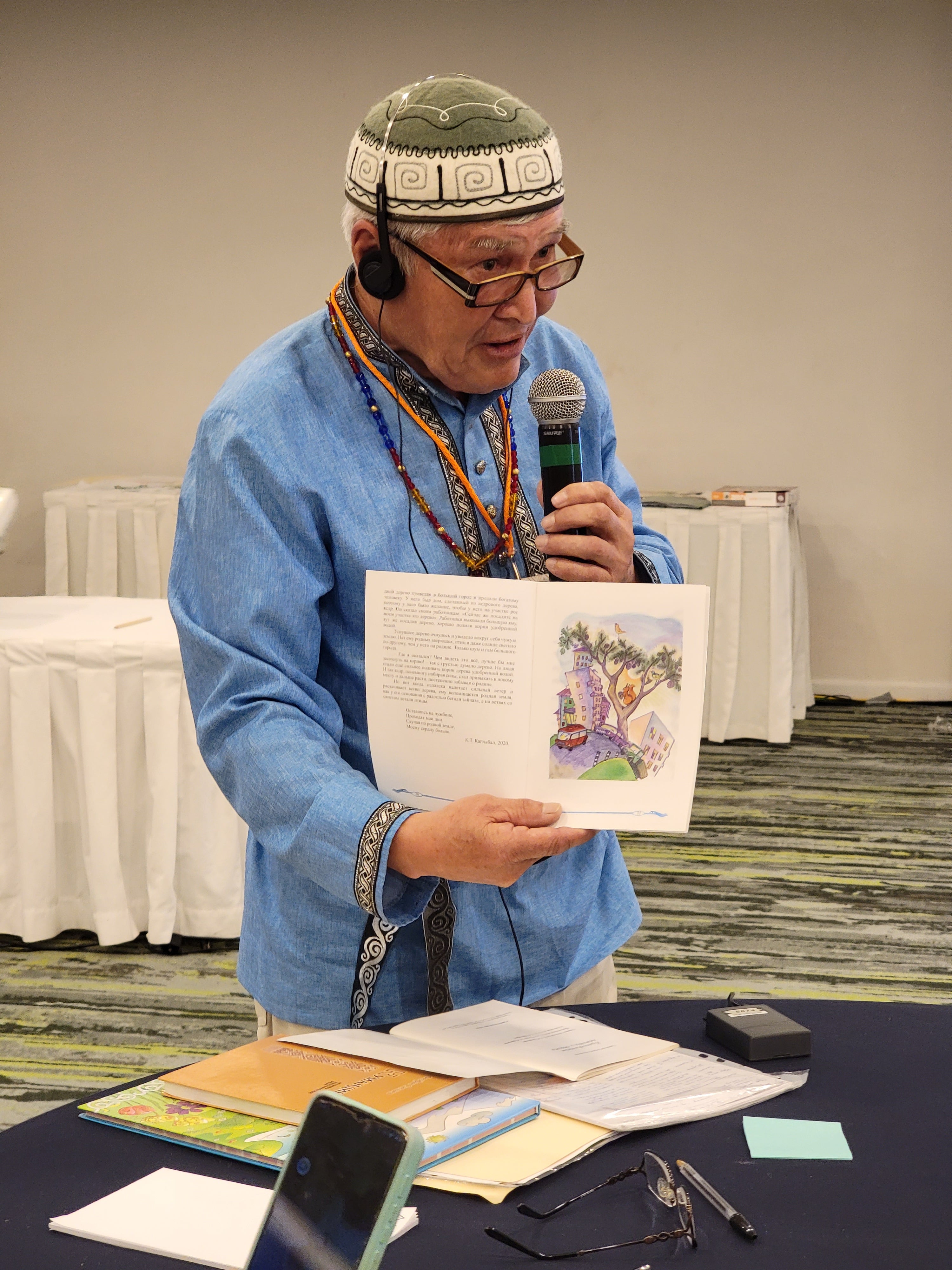

Kuttybai Kuttybal (Kumandin) from the Kumandin Language Project presenting his work to revitalize the Kumandin language.

Language learners spoke about the pains and frustrations suffered by their families as one of the emotional barriers to overcome before getting down to work. Kichwa members of the Quilloac community recounted having to hide their accents and cut their hair to go to university (Kichwa men traditionally wear very long hair). Nemuk’s team, from the Mixe Peoples, contributed that it is necessary to overcome the feelings of blame and shame that are frequent between parents and children, either for not having transmitted the language, or for not speaking it.

Most of the projects began with a diagnosis of their situation, assessing how many current speakers there are, how many apprentices will be trained, what resources are available, and what can be accomplished given the demands of daily life. By identifying the level of a language’s endangerment and the situation of the community, they were able to design an appropriate strategy. These took many forms, from the creation of language nests in Salish to teaching Ayöök as a second language, establishing an immersion school in Spokane, to documenting a language (Kumandin) with the last remaining fluent speaker. With the diagnosis as a starting point, the community projects got to work according to their particular values and needs. For some, such as the Colmix (Mixe) collective, which draws on 40 years of community planning, their previous work allowed them to diversify their teaching strategies and design written materials. Others are working to spark interest among their people, such as the Itelmen Language Project team, which is making a puppet film in the Itelmen language to reinforce a sense of identity and attract more people who want to learn the language.

Most of the projects agreed that the fundamental approach is to teach children to create new speakers. Written materials, such as dictionaries and grammars, are important but not essential for teaching the language. The Yuchi Language Project, Spokane Language House, and the Salish School of Spokane have achieved excellent results teaching their languages with methods that emphasize orality, such as songs, games, and language immersion in daily tasks. Other teams came forward and spoke in their native language, which would not have been possible for them previously.

Participants of the Grassroots Indigenous Language Exchange and Convening enjoy visiting Monte Albán in Oaxaca, a Mixtec and Zapotec archeological site dating back to 500 BCE.

Each linguistic community has its own unique set of needs, since not all learners are the same. They can be children, youth, or adults; they may know something, a lot, or nothing about the language. Those who already speak the language can focus more on writing and analyzing their language, while new learners may have other objectives, such as seeking safe environments in which to practice their language without the shame of making mistakes, as the Nemuk Collective pointed out.

The path to language learning is not a straight line. There will always be stops and starts, changes, and course corrections; it is a process of trial and error. Indigenous communities are trying out methods to strengthen their languages, they are building their own systems for teaching and learning language according to their culture and values. There is no one-size-fits-all method, even if the end goal is the same.

When community initiatives are anchored to larger community projects, they are more likely to succeed or progress faster. The Salish School of Spokane has engaged a large community of children and parents studying the language, as well as regular donors. The Vicente Guerrero Rural Development Project goes beyond linguistics; it is an organization of Indigenous campesinos who fight to preserve the land, the environment, and native seeds. In the Inga San Miguel de la Castellana Reserve, the work for the Inga language complements the teaching in the community schools.

Being part of larger projects that address other aspects of one’s own culture gives greater strength to linguistic efforts because the learners get closer to the culture, doing daily tasks such as weaving baskets or cooking traditional food while practicing their language. “Children learn at the foot of the Elders,” said Kaimana Barcase (Kanaka Hawaiiʻi), Cultural Survival Board Chair. “Language acquires full meaning in the daily tasks of the common life of our people,” added another participant.

Grounds has mentioned that language is a measure of the health of a culture. Perhaps so are these projects: if a community can come together for the future of their language, it means that they still have those values that have kept them in resistance for centuries. Although they face many obstacles, these Indigenous communities derive strength from their capacity to organize and work as a collective in a way that reflects their own spirituality, love, and respect for their Elders.

These projects focus on different languages and cultures with differing degrees of endangerment. However, during the Language Exchange and Convening, they were able to share their experiences and identify with each other, find common ground, and learn from one another about the different strategies for that shared goal.

While government programs (such as bilingual schools) continue to fail to redress the damages they have done to Indigenous languages and cultures, Indigenous communities are resisting by way of their own resources and knowledge. The structural discrimination of modern States has caused a lot of pain in Indigenous families. From that pain, a future is being built where our languages will continue to be heard and spoken.

Top photo: More than 50 language activists participated in the Grassroots Indigenous Language Exchange and Convening in Oaxaca, Mexico. All photos by Cultural Survival.