By Marco Antonio Martínez Pérez (AYÖÖK/MIXE)

Maaxïnkojm/Santa María Ocotepec is the name of my town. Located in the Sierra Mixe in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, it is a community on the slopes of the sacred Cempoaltepetl Mountain with a population of approximately 300 people. Maaxïnkojm is situated among banana groves and citrus trees; it is a town with a lot of vegetation because it rains almost all year round. The language we speak is Ayöök and belongs to the Mixe-Zoque linguistic family. Our language variant is spoken in at least 14 communities in the area. Like many other Indigenous languages, it faces displacement to Spanish, though there is interest and effort on the part of many people to transmit the language through reading and writing. The only school in the community goes to the primary level, so I left at the age of 12 to continue my studies. I now live in the city of Oaxaca and return to my town whenever possible.

My mother and father worked outside the community, so I grew up with my grandparents and older sister. I enjoyed living in Maaxïnkojm, perhaps partly because I didn’t know anywhere else. It was my place. Accompanying my late grandfather Zacarías, I learned some field activities such as cutting coffee, weeding the cornfield, and picking corn. More than helping him with the work, I think what he liked was my company. Our day in the field was spent planting trees, cutting bananas, or setting traps for the gophers that ate our yuccas. At noon, we ate xekmët (stuffed tortillas) that my grandmother had sent us and drank coffee.

With my grandmother, Juana, I learned other skills, such as tying a load of firewood and how to scream to scare away the hawks that were carrying away the chicks, or how to scare away the parakeets during times of rain. She taught me how to grind on her metate (mealing stone); she said I should learn to make my own tortillas. She would review my schoolwork, and when she made tamales, she gave me one of her platanillo leaves and told me to use it as a flag and march around the house. She was also the one who warned me about how risky it could be to swim deep in the river or climb a tree to try to cut some fruit.

My grandmother has a strong character and would scold us when we didn’t do our homework or spent too much time playing. “You must study because that’s why your parents work hard,” she told us. She reviewed our assignments with us and said that we should be prepared for what the teacher would ask in class. “It is very embarrassing if the teacher asks something and you don’t know the answer,” I remember her saying. She remembers perfectly what one of the first pages of her second-year book said, and even though she doesn’t know the meaning of many of those words in Spanish, she can still recite it from beginning to end.

I am very impressed by my grandmother’s memory. When telling stories, she shares details that transport us to that time and place and we can imagine the scenes. Sometimes she seems to wander off topic, but it actually gives us greater context of what was happening. “Jämïkxawe’e tö’k jayï tsyëë’n…” (“There a person came out”), my grandmother suddenly begins while we are cutting coffee at her ranch. Then she shares about some people who were going to cut pöptsï’ïp (a type of herb) from the mountain, but they did not offer anything to the Earth for the cutting, and then the Poj (a being that inhabits and protects the mountain) would appear, and the people had to manage to free it. She concludes her story with the lesson, “That is why they say that when someone cuts that quelite (wild greens), you must offer something to the Earth.”

What are the Maaytïk?

Maaytïk are stories that narrate an event from the past and are almost always accompanied by advice or a lesson. The stories have no authorship and may have multiple versions, such as stories about the origin of the town or some character in the community. Many of us can tell stories, but not all of us have the ability to delve into the details of places, smells, and sensations. Oy maajtykpata, we say to refer to those people who are good at telling these stories. Maaytïk have been passed down from generation to generation; what my grandmother tells was told to her by her mother or grandmother. There are also many Maaytïk that she says she does not remember who she heard them from. As linguist Yásnaya Aguilar (Mixe) says, the support of oral tradition is in memory.

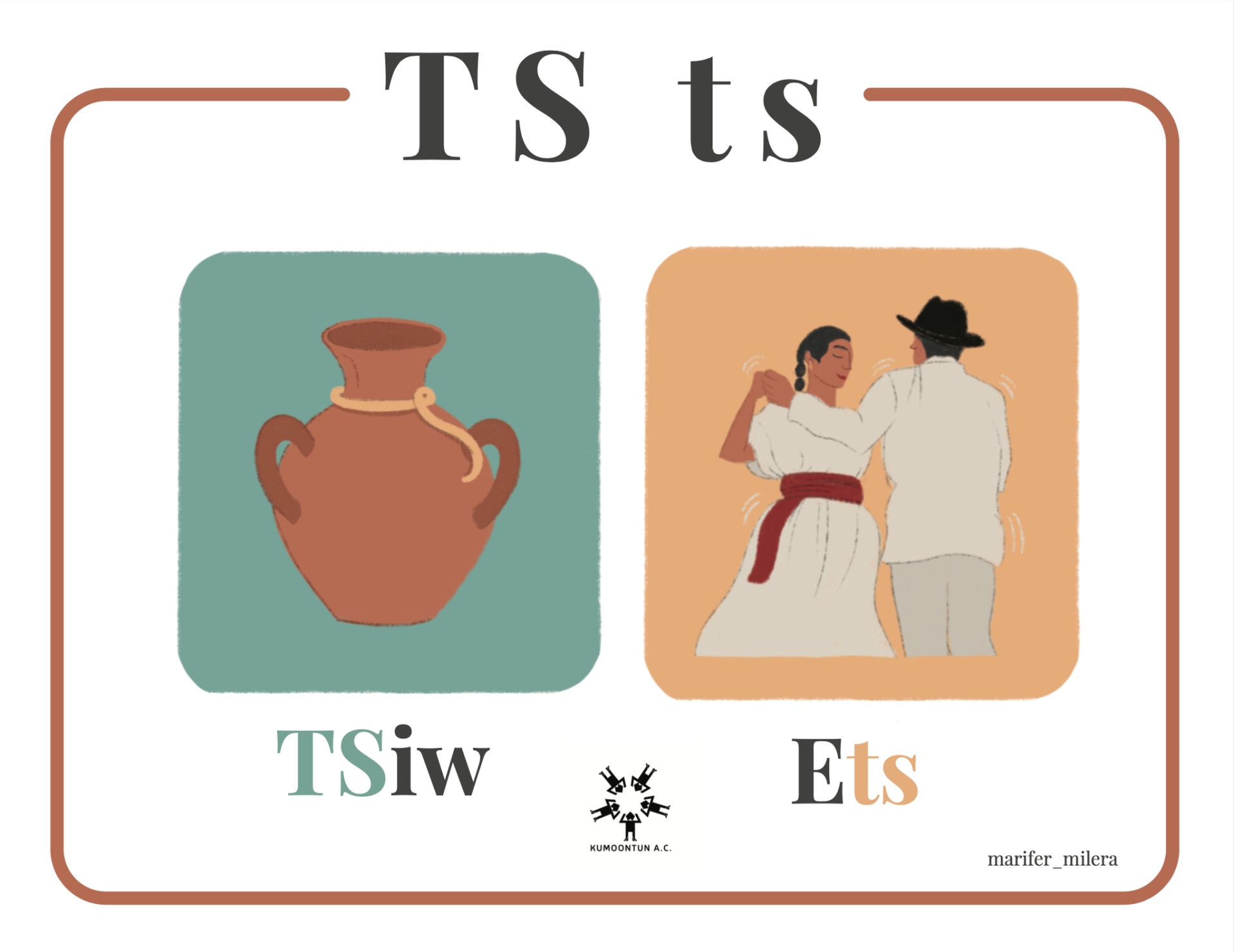

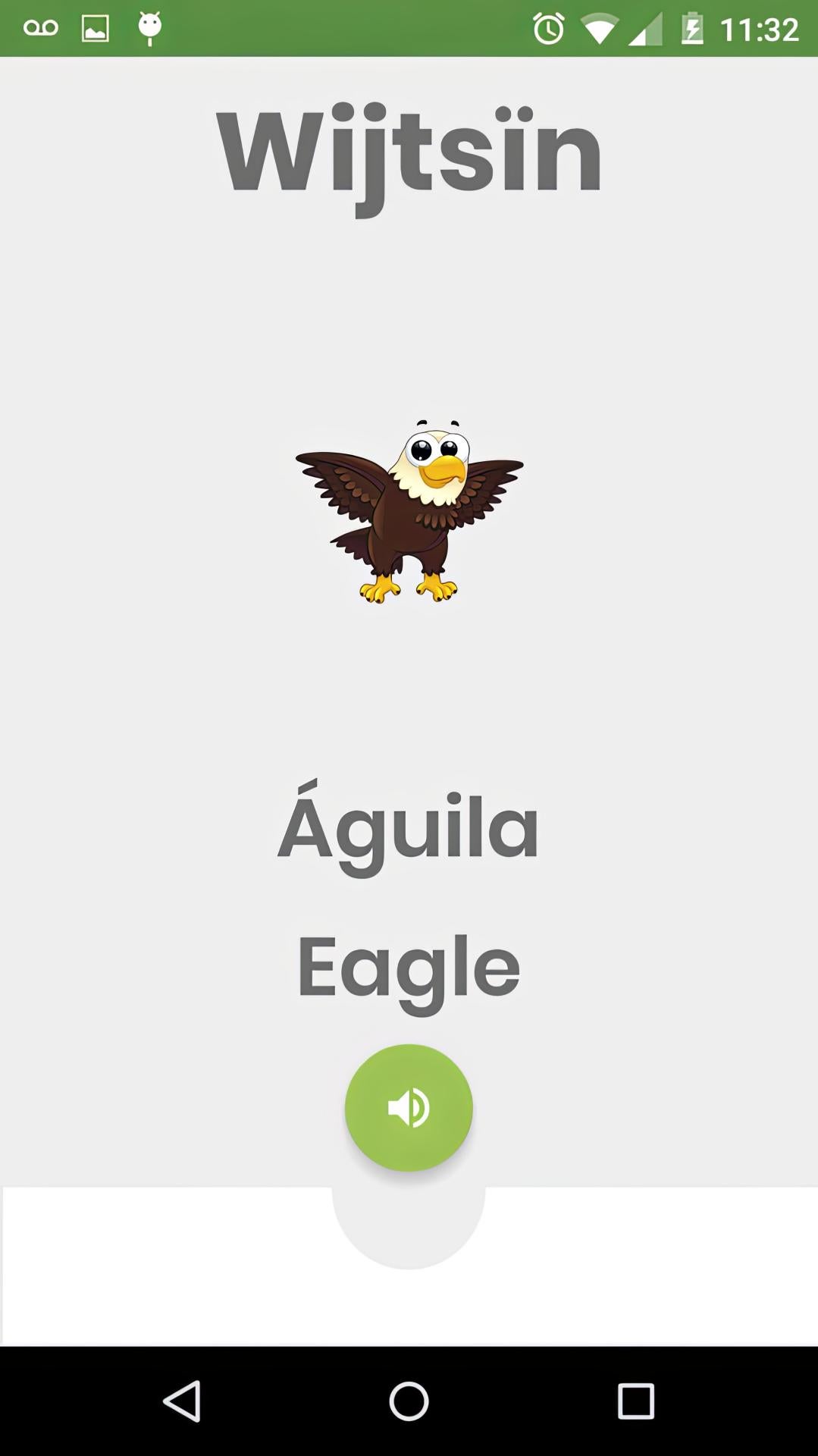

In a quest to document the language of our community, in 2018, we designed the mobile application, Kumoontun. In addition to creating an app that would use our language, we wanted to be able to transmit our experiences and the stories that are part of our oral tradition. So, we decided to integrate videos with recordings of community members sharing some of their stories to be preserved within the app. This presented many challenges—selecting the people and stories to include, recording and editing the materials, and, most complicated, storing the information. The solution we came to was to include six audio stories, three from the oral tradition that were stories that we knew in the family from the Maaytïk, and three we hadn’t heard before, which were produced by Engracia Pérez and Zitlali Martínez.

In 2019, one year after the launch of the Kumoontun app, we transcribed the audio and published “Ayöök Stories/Cuentos ayöök” as a PDF that brought together the six stories with links to the audio. This was possible with the support of the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples ( Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas - INPI). The audio recordings and the book serve as support materials during Ayöök literacy workshops aimed at strengthening our language. From the first version of Kumoontun in 2018 to now, it has been a time of much learning and reflection on our work and using digital tools to spread our language. We have identified areas of improvement, successes, and challenges for subsequent projects.

Children learning Ayöök on the Kumoontun App. Photo courtesy of Kumoontun social media.

Children learning Ayöök on the Kumoontun App. Photo courtesy of Kumoontun social media.

Today, I observe with great enthusiasm initiatives in different languages in different places supported by digital tools that document and disseminate the knowledge from oral traditions. Speakers of Indigenous languages are posting videos on TikTok and uploading content to their YouTube channels, using Zoom to teach online classes, and making films in their communities, among other ventures. At the same time that these projects are becoming more visible in an increasingly digital world, I think it is also important to reinforce the Maaytïk from the spaces in which they were originally told and transmitted to us. When I think about my grandmother wanting to tell me again a story that I have heard since childhood, I think about her memory and her ability to tell things and about the pleasure it gives her that someone is interested in listening. That’s why I often ask her followup questions: “And then what happened?” “Where did that happen?” “What were those people like?” Sometimes I approach her and start the conversation: “Nana, wintsookxa ijk ja maaytïk?” Nana, how does that story go?

Marco Antonio Martinez Perez (Ayöök) is from Santa Maria Ocotepec, Oaxaca, Mexico. He is a speaker of Ayöök and co-founder of Kumoontun A.C., which seeks to generate spaces and didactic materials that enable the strengthening and dissemination of the Ayöök language. He is also a collaborator at Rising Voices and a member of the Network of Indigenous Language Digital Activists in Latin America.

Marco Antonio Martínez Pérez showcasing his app, Kumoontun. Photo by Zitlali Martíne for kumoontun.org