In 2003, thanks to a summer scholarship provided by the American Field Service, I was sent during my second year of high school to Bolivia. One of the key field trips that summer was to the city of Potosí, a city that sits at one of the highest elevations in the world and more specifically, the city’s famed Cerro Rico mountain. Cerro Rico translates to the Rich Mountain, having earned this name when enormous quantities of silver were found there during the time of the Spanish conquest in 1545.

Within years of this silver discovery, large-scale extraction and exploitation of this resource from its source in the heart of Quechua and Aymara lands was underway, with this silver wealth funneled directly to the coffers of the Spanish Empire. Potosí not only became the largest city in the so-called New World during the 1500s, but locals claimed that enough silver was taken out of Potosí to construct a bridge stretching from South America to Europe. Even when the quantities of silver began to wane, tin and other minerals such as lead and copper quickly became the next focus of extraction that has continued into the present.

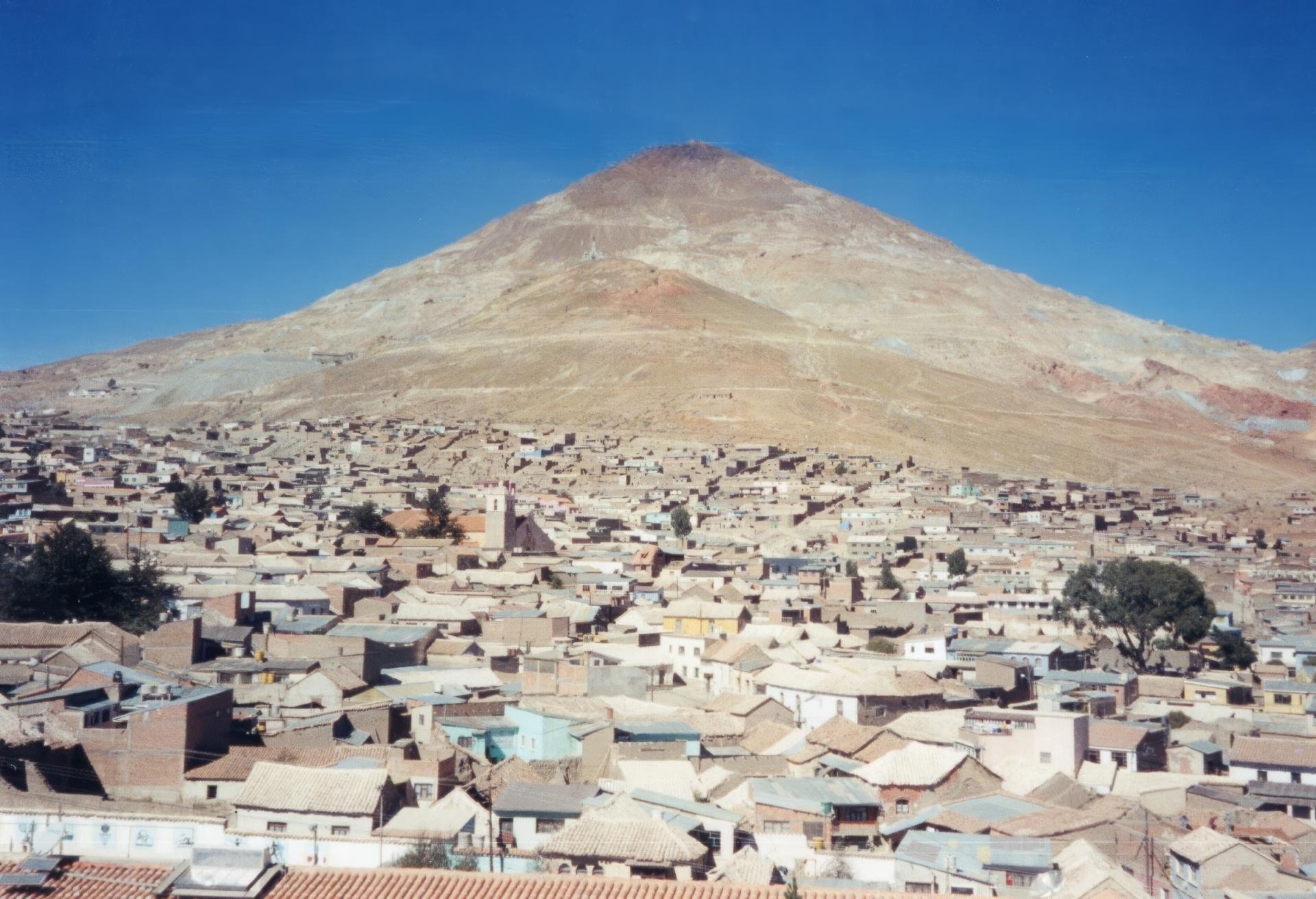

A view of Cerro Rico mine in Potosí, Bolivia in 2003.

Cerro Rico is also known by another name: el cerroque come los hombres, or “the mountain that eats men.” As a student that summer in Potosí, I witnessed firsthand how it acquired this name during a program field trip led by two miners who took our small student group deep into the mountain on an official mine tour. Equipped with working suits, hardhats, and flashlights, other compulsory items we had to purchase before entering the dark caverns included cigarettes, coca leaves, and small bottles of 90-proof alcohol—the favorites of Tio Diablo, or “Uncle Devil,” who oversees everyone and every activity that happens deep in these mines.

Honoring the Tio Diablo with offerings of coca leaves, cigarettes and alcohol to ensure that we are given safe passage through the mine.

Following the protocol of the miners, our first stop was to pay our respects to Tio Diablo, asking his permission to enter the subterranean world that is his domain and offering our gratitude. After lighting a cigarette and placing it in the statue’s mouth, we moved on to the other levels of the caverns, watching miners that ranged in age from their early teens through their mid-40s toiling away in backbreaking conditions with basic tools for hours at a time. Many, if not most, of these miners would develop debilitating silicosis, we were told.

I was profoundly shaken, transformed, and radicalized by what I had seen in the mine. This tour offered a glimpse of colonialism, extractivism, and exploitation of people and Pachamama in its most raw and tangible form. Beyond the haunting scenes of what I observed in the mine, the visceral reactions have also stayed with me to this very day of what colonialism, extraction, and injustice can taste, smell, and feel like. It’s something that I have never forgotten.

The Potosí mine tours have not stopped, and neither has the mining and ongoing extraction of the minerals that form the basis of our world economy and modern technologies. In addition to the more traditional forms of hard rock mining that goes on in Potosí and other areas of Bolivia, a new wave of mining for transition minerals is central to the transition to the so-called green economy. Returning to Bolivia and also having the opportunity to visit Chile in 2024, I was hosted in two of the three points of the “Lithium Triangle” in South America. This area is located in the highlands shared by Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile and is where some of the world’s largest concentrations of lithium are located.

On the outskirts of the Bolivian highland town of Coro Coro, historian and activist Carlos Mamani (Aymara) defends his community’s sacred lands and cultural sites from copper mining, and is also an advocate for the importance of the traditional governance centered in the ayllu system, which designates traditional nations. According to Mamani, the location of his community’s ayllu was related to their traditional practices of salt harvesting, an activity that his community has maintained from time immemorial into the present.

The primary area of salt cultivation in Mamani's ayllu, or traditional Nation, which includes stacked salt blocks under straw covering to the right.

With the support of a Keepers of the Earth Fund grant, Mamani is assisting his community to keep this tradition of salt harvesting strong while also exploring opportunities for community members to earn an income through salt sales. Mamani is also raising awareness about the Bolivian law stipulating that any resources taken from underground and then evaporated belong to the Bolivian State. While on the surface this law would seem to apply only to lithium, Mamani says that this law “also potentially has ramifications for cultural resources such as salt cultivation and the sovereignty of ayllus to maintain these ancestral practices.”

Following the trail of bright white salt down southward in Bolivia, Jiliri Mallku Efrain Quispe (Aymara), a traditional leader, or Jiliri, within the Marka Tahua network of communities, takes me by four-wheel drive into the heart of the Lithium Triangle. The center point of gravity stands in the Salar de Uyuni, or Uyuni Salt Flat, the largest salt flat in the world. Its white expanse is dotted with small islands that are hubs of life for cacti and small animals, and a major draw for tourists from around the world.

The network of 13 communities that form Marka Tahua, one of the key jurisdictions that comprise the traditional owners and stewards of the Uyuni salt flat, is concerned by the water usage impacts of lithium extraction that they are already seeing on their sacred salt flat. United in their opposition to the lithium extraction, Marka Tahua leaders call for investment into cultural tourism, and are using their KOEF grant to construct traditional cultural infrastructure on the island of Qujiry/Isla del Pescado, which will aim to attract tourists. Quispe says, “We want to give the tourists a glimpse into our way of life, our cosmovision, so that they can understand it is we, as the Ponchos Blancos (the traditional dress worn by authorities), the Marka Tahua Original Autonomous Government, who are caretakers and maintain authority over the Uyuni Salt flat.”

Marka Tahua leaders standing in front of the initial progress of cultural tourism infrastructure building on Qujiry island.

Exiting the Uyuni salt flat and crossing the border into northern Chile’s Atacama desert, the local Indigenous communities of the San Pedro de Atacama region are on the frontlines not only of some of the most extensive lithium extraction operations, but also major waves of tourism. With lithium operations consuming massive quantities of water in the driest desert landscape in the world, several communities have expressed opposition to specific industry practices, particularly involving water usage. Led by Indigenous members and tour guides of the communities of Toconao, Coyo, and Quitor, these community members explain how they are balancing the needs of a growing tourism presence with increasing demands for water by the mining industry. In Toconao, traditional irrigation systems that have helped to nourish the community and have kept it fed for millennia in the driest climate in the world are spotlighted as an important site for cultural tourism. Even more significantly, this traditional irrigation technology is evidence of ancestral Indigenous brilliance and stewardship continuing into the present as our global climate becomes more unstable.

Water flowing along the irrigation canals in the Toconao community in northern Chile’s Atacama desert.

While the mining sites, processes, and minerals of today’s quest for transition metals may look different from the conditions that can still be witnessed in mines such as Potosí, it is imperative to continue to critically examine the impacts of mining upon living communities. After all, it is these communities, which include Pachamama, that allow mining, tourism, and other industries to exist in the first place. The faces, Traditional Knowledge, and insights of the communities on the frontlines of the Lithium Triangle have much to teach us about the true contours of what “green” technologies and economies mean for our relationships to a living world that deserves our stewardship and respect.

Acknowledgements

Bobbie would like to express deep thanks to the following organizations and individuals that made these journeys possible: Marco Lucero of Cuidadores de Destinos (Santiago, Chile), Unidad de Turismo Municipal (San Pedro de Atacama, Chile), Mr. Carlos Mamani, Jiliri Mallku Efrain Quispe and the Council of Original Autonomous Government of Marka Tahua, and Ximena Calle and family.

Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee) is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, where she researches the intersections between Indigenous-led tourism and resurgence. This article is part of a series that elevates the stories and voices of the Indigenous communities and land defenders in the Lithium Triangle.

Top photo: A group of Marka Tahua traditional leaders standing on the Uyuni salt flat and looking towards Qujiry island.

All photos by Bobbie Chew Bigby.

READ: Reclaiming Sovereignty Through Salt and in Spite of Extraction: A Journey to Ayllu Yaribay

Top photo: A group of Marka Tahua traditional leaders standing on the Uyuni salt flat and looking towards Qujiry Island, Bolivia.