December 23, 1988, the day of Chico Mendes' murder, Marlise Simons fervently praised the life of the Brazilian labor leader and environmentalist. The New York Times correspondent in Brazil, Simons called the National Council of Rubber Tappeers Mendes headed "the only group that physically prevented deforestation." She placed responsibility for the violence that claimed his life on the shoulders of the wealthy ranchers who profited from destroying Brazil's vast rain forests.

In measured words, Simons also brought the international development banks into the tragic drama. "Both the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank have lent large sums to Brazil to build a road to Rondonia and Acre that opened up the virgin forests of the western Amazon," she wrote. "But Brazil has not lived up to all the requirements of the loan agreements to safeguard the rights of Indians and other forest peoples. Land speculators [along the road's path] have often violently expelled the inhabitants."

Times editors put Simons' article on the front page the following day, and in the week to come other reports and columns in most influential newspapers in the United States called attention to the plight, and strugglers, of the people living in the world's largest rain forest. Times reporters and columnists clearly sympathized with Mendes' cause and gave his allies some cheer in an otherwise melancholy week.

The Times coverage of the murder of this Brazilian rubber tapper was not an exceptional event for the paper. U.S. and Brazilian activists had come to count on the "paper of record" for sympathetic coverage of Amazon events, a situation that might surprise critics of the paper, who often have good cause to grumble over its slant on domestic and international politics.

The coverage was not accidental. Environmental and human-rights activists worked hard to court The Times - and other major media outlets - on the Amazon issue. As a direct result, the mainstream media has provided activists with added leverage in their efforts to shape the policy of the U.S. government and the multilateral development banks vis-a-vis Brazil.

A MEDIA STRATEGY

Enlisting the media as an ally in campaigns for human rights and environmental sanity in the Southern part of the world is not an easy task. Aside from media biases, cultural affinities, and economic interests that frequently favor elites, there is the question of longstanding "professional" opinions of what constitutes a newsworthy story. "An absence of human rights in distant and exotic places is almost the exact opposite of news," suggests Stephen Schwartzman, an anthropologist employed by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). "What's expected of the Third World is mayhem."

Despite such constraints, Schwartzman and others decided the media would be an important element of their campaign to pressure international lenders - for example, the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), and Asian development banks - to clean up their Third World behavior. EDF, the National Wildlife Federation, and other national environmental groups launched this campaign in the early 1980s based on several factors. First, they saw close links between economic development and ecological and human-rights abuses. Moreover, the banks wielded great power over both development policies and individual projects. Finally, the target could be hit close to home, since the U.S. government is the largest contributor to the bank treasuries.

The activists focused on pushing the World Bank to change three plans it was funding: a dam in India, a forestry project for Indonesia, and the construction of the Amazon highway, BR 364. The strategy faltered in Asia, as few major media outlets dispatched reporters to the affected areas of India and Indonesia. In Brazil, the campaign took hold.

BR 364 was designed to link scattered Amazon settlements with the national highway system. Peruvian roads, and ultimately the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. In the early 1980s, the World Bank lent $350 million for the first stage of the road from Cuiab to Porto Velho. Highway construction opened up the vast Amazon region to farmers, ranchers, and timber traders. In so doing, it set off a chain of events that ended with the burning of ever-larger swaths of forest land, the destruction of indigenous economies, and the eviction from their communities of long-term forest dwellers.

"Using the media turned out to be of fundamental importance," Schwartzman argues. "It provided a lever on Congress," which controls the flow of U.S. funds to the bank. In response to his efforts and those of his allies, alternative publications at first, and later major media, started documenting the impact of road construction. Reporters showed how the Brazilian government wasn't living up to its promises to protect forest dwellers, and they exposed to U.S. readers the violent reaction of ranchers and speculators to popular resistance. As newspapers covered the clearing of large areas of rain forests for ranches, they drew connections between environmentally destructive activities and the World Bank-funded roadway. (One person Schwartzman convinced that Brazilian rubber tappers were newsworthy was the news editor of Technology Review, who now edits Cultural Survival Quarterly.)

Since the campaing originated in Washington, media attention also helped build a constituency among U.S. environmentalists to oppose bank projects in the Amazon region. "International issues get little attention within the environmental community," says Schwartzman. "The press was essential to get the environmental community aware that it could do something." The media helped spur informal lobbying on the issue by environmentalists, and it provided a forum for them to express their desires through editorials and opinion pieces.

Congress felt the heat. According to former Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt, a frequent writer on the Amazon, "By the time the road reached Porto Velho, the World Bank was coming under scrutiny not only from environmentalists but also from members of Congress."

In 1985, the World Bank pulled back, refusing to fund further stages of the project. Brazil turned to the Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank's regional counterpart. After some delay, in part due to controversy over the project, the IADB funded the next two stages. Still, pressure from environmental groups, including EDF and the National Wildlife Federation, forced it to pay at least lip service to asking for assurances that indigenous peoples and the rain forests would be protected.

BUILDING THE CAMPAIGN

Despite the IADB's funding of the Brazilian road, environmentalists viewed the World Bank's retreat as a victory. They also knew their campaign would continue, not just to get the development banks on board, but to influence overall World Bank policy.

Not only did it continue, but it acquired a new dimension: Brazilians began to speak for themselves in U.S. media and Washington policy debates.

"In 1986 at a meeting in Brasilia, a field representative of the Environmental Defense Fund [Schwartzman] met an unknown rubber tappeer and peasant leader from Acre named Chico Mendes," Babbitt reports. "It was a serendipitous encounter that united root and branch of a gathering international protest movement. International environmental organizations found a Brazilian grassroots connection, just as Mendes and the forest people of Acre discovered a sympathetic world audience."

Personal contact was crucial in promoting Mendes in the United States. As the media campaigners had done in the case of sympathetic scholars, analysts, and activists, they took paints to introduce the union leader to editors, reporters, and correspondents in Washington and Rio de Janeiro. Long before his murder hit the front pages of The New York Times, Mendes became a major asset in the media wars being waged by U.S. organizations. Likewise, Brazil's some 200,000 rubber tappers, who collect native latex from which rubber is made, became frontier folk heroes.

Soon after the Brasilia encounter, the EDF and other groups brought Mendes to Washington, D.C., for the annual meetings of the IADB board of governors. In Washington, Mendes met reporters and editors and impressed them with his knowledge and creativity. A labor struggle in the Amazon might not strike U.S. newspapers as important, but rubber tappers who engage Northern bankers and Brazilian bureaucrats in intellectual and political battle are news.

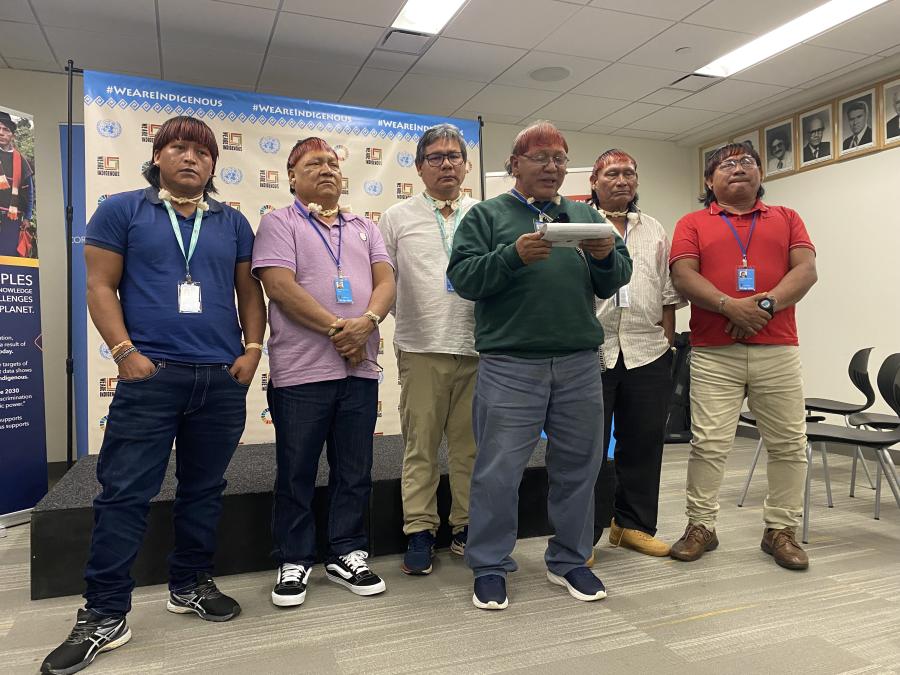

Mendes was not alone in battling Northerners. José Lutzenberger, a noted Brazilian environmentalist, and Ailton Krenak, national coordinator of the Union of Indigenous Nations (UNI), traveled to Washington in 1986 to address the Citizens' Conference on Deforestation. Krenak met with World Bank and IADB officials as well.

"The ingenuity of the rubber tappers was their ability to frame a positive alternative, to present an alternative way of doing things," says Schwartzman. "There was news. There was novelty that rubber tappers would come up with a better plan."

By the end of 1986, the campaign had convinced Congress to require U.S. directors of multinational banks to push for environmental reforms. The legislation aimed to encourage the involvement of nongovernmental organizations like UNI and the National Council of Rubber Tappeers in development plans.

Reagan-appointed directors of the bank did, in fact, do what the legislation said. For example, they opposed, although unsuccessfully, a controversial Brazilian dam.

THE ROLE OF CIRCUMSTANCES

Poor people in many parts of the world have come up with intelligent ways to use their lands and fight encroachment, yet they rarely become headlines. The U.S. media basically ignores grassroots alternatives to bank development schemes. "We needed to convince journalists that Americans have a stake in the Amazon forests," says Schwartzman.

Factors outside the campaigners' control were at work drawing attention to Brazil, allowing Schwartzman and his colleagues in the United States and the Amazon to appeal to the media on its own terms. For example, scientists had begun to draw the attention of journalists to global warming and tropical deforestation. Rainforest advocates often pointed to the links among global warming, the burning of the Amazon, and the conservationist methods of the rubber tappers.

In addition, Brazil's alarming debt, and the country's difficulties in repaying it, was hot news in the 1980s. With Brazil owing foreign creditors some $100 billion, reporters were already looking at the country's troubled relations with international bankers; deforestation added an angle to that story.

Finally, Brazil is in the Americas. That makes it part of what many politicians and editors, liberal and conservative, have long regarded as a "natural" sphere for U.S. activity, influence, and responsibility.

A MARTYR AND THE MEDIA

Still, up until 1988, the media paid only sporadic attention to battles over the Brazilian rain forests and the role of the development banks. In many papers, like The Times, the coverage frequently sympathized with the activists. But The Washington Post and other papers were less likely to criticize the banks. Generally, the campaign was proceeding positively, if slowly.

Mendes' death made the Amazon a big story, one that leading newspapers and broadcast networks all featured. Mainstream intellectual journals like New York Review of Books and Foreign Affairs discussed it, and several well-received books were written about it. The media had what it couldn't resist: a martyr.

By this time, the media coverage was fitting into a movement to reform bank environmental policy and rainforest development strategies that had matured and reached international proportions. European cabinet members put environmental policy at the forefront of their agendas, the Prince of Wales added his voice to the clamor, and grassroots organizations were arising throughout the Third World.

Of course, using the media has its limitations. Ever so fickle, journalists treat the news as top-40 radio treats music: Brazil was hot, India was not; one story made the front page of The New York Times, the other the inside of In These Times. And few editors support the more far-reaching proposals that many activists, especially in the South, believe are needed to halt the rape of the tropics. Overall, the World Bank adheres to its ultimately unsustainable vision of an ever-growing world economy and lightly regulated market economies. Its less-visible regional sisters, like the IADB, have even further to go.

That said, the media has played a role in building a movement to protect the rubber tappers and rain forests of Brazil. It has helped Schwartzman and others educate the public, enlist new adherents, win legitimacy in international forums, and pressure the bankers. The World Bank has declared environmental sanity a major considerations, even if its practice remains contradictory.

Resources: The Media

The media frames much of our public debate, playing a large role in how people and issues are perceived. Thus, attending to the media can be vital to self-determination. It also requires overcoming media biases, such as whom journalists consider a spokesperson.

Just like any campaign to change policy, media work begins with a strategy. What role can the media play in your campaign? Who are the targets? What resources will it demand - and drain from other tactics - and what are its benefits? How do efforts to influence the media fit the broader campaign? In short, how can the media help you get what you need?

If you decide that media work is worth your resources, focus on cultivating long-term relations with reporters and editors, rather than getting one-shot coverage. Ideally, you will become a regular news source. Your ultimate goal is to have native peoples' voices and views appear in the U.S. media.

To succeed, you must be sensitive to what the press wants and be able to recognize issues from its point of view. The press looks for credible and available people who tell the truth, speak the right language, have the proper status, and provide ideas and access to unique sources.

It is often best to set up a media committee. This group will have two tasks: one offensive, one defensive. You must place native affairs in the forefront of the media's attention while also responding to negative, incorrect, and distorted coverage.

The committee and your organization should focus on a few key "talking points" that you want to make in all contacts with journalists. The committee should also monitor coverage, raise consciousness about how indigenous affairs are covered, and prepare for its encounters with the press. Learn to read the paper and watch TV to pick up images of native peoples, human rights, and environmental issues.

Don't assume that editors and reporters understand anything about indigenous issues. And don't ever say anything to a journalist you don't want to see in print.

PROMOTING PROGRAMS, ISSUES, AND PEOPLE

Your main media outlet is the local newspaper, so learn the names of the editors (usually listed on the editorial page) and the by-lines of reporters likely to cover your issues. The goal will be to get the paper to run both editorials endorsing good policies and feature articles on the issue, as well as to have columnists support your efforts. Keep in mind that newspapers always need good material. Ideally, you will become a regular source for stories, ideas, and comments.

Newspapers take positions on both local and boarders issues, although small papers often want a hometown hook when they cover national or international issues. Editorial positions are decided by the publisher, the managing editor, or, on large papers, an editorial board that can also include the editor-in-chief, editorial page editor, and editorial writers.

MEETING THE EDITOR

Editors have power: if you want to change how a newspaper covers native rights, arrange to meet an editor or the editorial board. You want them to be sympathetic to the rights and needs of native peoples. Your goal is to get them to make their paper a forum for native voices and needs.

Before making this contact, know whom you want to talk to. Find out if the paper has taken a position on your issue. If you know a reporter, ask her or him for suggestions on how to approach editors. Read the local paper with an eye to what it says and who at the paper says it. Editors respond to readers who can refer to specific articles and editorial positions. It's fine to disagree with editors - they expect that. Editors don't have to love you, just think that you are credible and newsworthy.

To arrange the meeting, write one of the people on the board. Explain your issues, who your group is, and why you feel the newspaper should take a position. Stress why you want to meet, what you have to offer them, and who will come to the meeting. If relevant, tie the request to the paper's recent coverage of indigenous affairs. Be concise and explain your request succinctly.

Before the meeting, have your own meeting to decide who will say what, the points you want to make, what materials to bring, and what you want to get out of the meeting. Keep the delegation small, perhaps three people, and make sure there is a good reason for each of you to take part.

Come to the meeting armed with facts and with a specified purpose. Present the board or editor with background information on your issue, including whom to contact to learn more. Explain why a new policy is needed and why the newspaper should take a position. Be honest and open.

After the meeting, send thanks and the material you promised. Repeat the key points of the meeting and remind the editor to contact you. Later, send more information regularly, but don't call or write too often; have a reason for each contact.

If the meeting results in a positive editorial, send it to your members of Congress and to Cultural Survival. If the newspaper decides not to take a position or opposes your view, ask it to run an oped. Be prepared to provide the name of someone to write an op-ed.

GETTING FEATURED

The best way to place a feature story on human-rights issues is to target reporters who cover a relevant beat, such as the environment, politics, or science. Promote your story to them, appealing to their sense of news. They want stories with immediacy and local appeal.

Use the same strategy when contacting colunnists but remember: columnists take positions. You should know a columnist's view on related issues before making contact.

Another good way to get a message across is to write an op-ed. Look over the tips for writing letters to the editor; many of them apply to op-eds. You can send your article in with only a cover letter, or you can write a query letter first. In either case, a wait a week or so and then make a call to follow up.

You can also get your message heard by tuning to talk shows broadcast on radio. Radio talk shows have wide, loyal followings, and most cities have several local celebrities. Call in to a talk show to offer your comments on the subject being discussed or to bring up your own issue. During the call, mention your group's name and any relevant events or campaigns. If you have a particularly interesting story, contact the radio station to see about arranging an interview.

PREPPING THE PRESS

Press releases are the most regular contact you'll make with the media. Besides generating attention and articles, press releases keep journalists aware of you and your issues. They build your image as credible and newsworthy. A press release should tell a story, before and after an event, and help raise awareness of the importance of the rights of native peoples.

Every press release reflects on you and your cause. Only send a release when you have something to say that might interest the media. Reporters and editors want a peg, such as an event you are scheduling or a tie to breaking news.

Give press releases the preparation time they deserve. Your wording often appears in a newspaper with little editing. Examine a paper for writing hints. Use short, simple sentences and strong, active verbs. Be factual, avoid flowery language, and include some quotes, especially for subjective statements.

The first paragraph of a press release is critical but demanding to write. Ideally, it seizes the reader's attention and also answers the traditional journalism questions: who, what, why, when, and where. Press releases are different from an essay. All the important points come first, rather than in a dramatic conclusion. Remember to quote key people by the second or third paragraph.

Briefly describe your group in the last paragraph. And to ensure that your group gets mentioned, include the name elsewhere in the release, even in the first paragraph. Don't forget that your group's phone number, address, and contact person should be on the release.

Rewrite often. Cut whatever you can. And keep the release under two pages. (Don't cheat by using small type.) Always type the release, double spaced with wide margins.

Make the release stand out from the hundreds of others editors receive. Have a strong, catchy title. Include your group's log and consider printing the release on clored paper.

PRESS CONFERENCES

A press conference is an event centered around people talking. Press conferences take a great deal of work, time, and resources. As with any other part of organizing, a successful press conference must be worth the effort. No matter how important the cause, a press conference wastes resources if the press doesn't show up or report on your presentations.

That said, the rules for a successful press conference are straightforward.

Pick the right speakers and rehearse them. All speakers need to understand the group's gals for the press conference. They must give brief, succinct answers that stress main themes.

The media committee should consider the likely questions and how to answer them. Be prepared. Speeches should incorporate "sound bites."

Talk the reporters' language. Use approximate numbers. Avoid jargon and rhetoric. Be colorful and contemporary and even talk in cliches. Be personal. Stay calm.

Speakers should say when they don't know an answer. Someone in the organization should follow up later and send the answers to the reporter.

Give advance notice of the conference by sending a press advisory to editors, news directors, and reporters. Send reminders three days ahead and make last-minute calls the morning of the event.

Pick a site reporters can reach. You might want to connect the site t the reason for the conference. For example, you might hold it in an airport room for a visitor arriving from abroad.

Most conferences occur between 10 and 4 on weekdays, earlier for newspapers, to meet deadlines. Keep it short; no more than 30 minutes in all, with at least half that reserved for questions and answers.

Control the conference. Have a press table with sign-in sheets. Greet the press, direct them to spokespersons, and monitor whom they talk to.

Start to time, and keep on time. Cut off long speeches. Spread out the questions. End on schedule and have the speakers available for individual interviews.

For TV, provide visuals. Have placards around the room, charts to illustrate key points, and your banner on the podium.

At the press conference, distribute a press kit with a release summarizing the main points of the presentation, information about your group (and Cultural Survival), and additional information, maps, charts, speaker bios, etc.

After the press conference, quickly respond to request for more information, call key reporters who didn't come, monitor coverage, correct errors with letters-to-the-editor, and send thanks for good coverage.

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

According to a survey by the Center for Practical Politics at Rollins College, Florida, "Letters to the editor provide one of the single most influential channels by which an active citizen can express ideas about timely subjects of general concern." Letters to the editors of magazines and newspapers address large audiences and are the most widely read section except for the front page. Your readers will be a cross-section of the population, and policy makers, including congressional representatives, will be among them.

Your chances of getting a letter published are high if you don't live in a big city. The Star-Tribune, Wyming's largest paper, publishes 95 percent of all letters received. Recruit two or three people to write letters regularly, and the results will be significant.

Letters to the editor help supply the truth on issues that may be slanted or omitted in news reports. They raise the visibility of the issues and people you are concerned about. They enable you to bring moral judgments t bear on human-rights issues, to appeal to the public's sense of justice and decency. * Type your letter and double-space it. The average length should be about 250 words - one typed page. A longer letter is acceptable if the editors think it has sufficient reader interest. On the other hand, editor often shorten letters to a few paragraphs. So rewrite the letter often, cutting out what isn't absolutely necessary. * Deal with a single topic in a letter. Refer to an article or set f article in the periodical you are addressing. Read this article carefully. * Use short sentences and simple words. You want to send a message, not impress people. * Plan the first sentence carefully. Make it short and topical. Think about what readers will think, not only what you want them to think. * Even if your letter attacks a policy, avoid violent language. Begin with a word of appreciation and end with a constructive suggestion. A calm representation achieves a great deal. Still, show your strong feelings and bring in personal experiences to illustrate points. Your experiences give credence to your views and make them more newsworthy. Journalists eat up eyewitness accounts. * Be specific. Instead of saying "change U.S. policy toward indigenous people's ask readers to "support the Pan American Cultural Survival Bill." * Sign your name. If you represent an organization, include your title. * Keep a copy for yourself. * Send the letter, with variations, to newspapers or magazines in other cities. * If your letter is published; send it to your members of Congress, others h might be influenced by it, and Cultural Survival. * Don't give up looking for your letter too soon. It won't appear for at least a week. And keep writing. If one letter in ten runs, you will reach an audience that makes it worth the rejections.

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENTS

Public service announcements function like ads - but are almost free. You only pay for the cost of the materials and the labor you invest. PSAs can publicize your group, event, cause, or a combination of these. PSAs are normally for radio and TV but also appear in print (see sidebar on page 53).

Stations use PSAs to serve the public interest and to fill unsold advertising time. They chose PSAs that are well-written, community-related, and persuasive - and when pushed to do so.

There are two steps to consider when doing a PSA. The station has to be convinced to accept it. And it has to give the right message and do so effectively.

Begin by contacting each station's public service director to get the rules on submitting PSAs, what is acceptable, and what format to use. Address all correspondence about the PSA directly to this person.

After you write the first draft of the PSA, read it aloud and then rewrite it. Repeat. Especially when writing for the radio, consider what the PSA will sound like. What will people hear? For TV, also consider what they will see.

PSA are very brief, and the timing has t be accurate. A 20-second announcement can include about 50 words. You can pre-record the script or send in a written version for reading by station personnel.

Radio stations eat up PSAs and may welcome new material every few months. Submit TV materials at least a month ahead of schedule, with new material not before three months.

Send your PSA to every local station that uses them.

SPREADING THE RIGHT STUFF

The mainstream media isn't your only outlet. The "alternative media" tend to be more political, more daring, and less profit-driven than the regular media. Since many of the alternatives concentrate n a particular subject or political, ethnic, or other affiliation, they are a good way to target sympathetic audiences.

Although alternative media have sprung up both nationally and locally, they are seldom well-funded and often have low budgets for advertising and distribution. And because it can be hard to find or access alternative media, even in cities, most f us miss a lot of good programming and publications.

You can bring alternative media to your hometown be encouraging local TV, cable, and radio stations to buy programs syndicated by such sources as Deep Dish TV and pacifica Radio. Sometimes this service costs nothing: Z Radio will provide free programming t radio stations. Target newsstands with a "boycott" campaign for alternative newspapers and magazines.

Almost every city has a public-access cable channel. Community cable is always looking for material, and most stations are open t non-traditional types of programming. Get them to carry your favorite alternative productions regularly.

You can produce your own video program for your local community channel, even without a large budget. Many channels supply the equipment, but you will, however, need lots of imagination.

RESOURCES

Melba Beals, Expose Yourself: Using the Power of Public Relations to Promote Your Business and Yourself (Chronicle Books, 1990) $18.85.

Virginia Bortin, Publicity for Volunteers: A Handbook (Walker and Co., 1981) $10.95

The mechanics of using the media

Center for Investigative Reporting, 530 Hoard Street, 2nd floor, San Francisco, CA 94105 (415)543-1200

Sells "Raising Hell: A Citizens Guide to the Fine Art of Investigation" $3

Center for Media and Values, 1962 S. Shenandoah, Los Angeles, CA 90034 (310)202-7652; fax: (213_559-9396

Develops new ways of thinking about television and media, along with new tools for educating adults and youth about media images and their impact. Publishes Media & Values magazine ($14 per year) and a newsletter and produces Media Literacy Workshop Kts

Center for War, Peace, and the News Media, New York University, 10 Washington Place, 4th floor, New York, NY 10003 (212)998-7960

Publishes Deadline on peace, security, and disarmament issues

Wicke Chambers and Spring Asher, TV PR: How to Promote Yourself, Your Product, Your Service, or Your Organization on Television (Chase Communications, Inc., 1986) $14.95

Deep Dish TV, 339 Lafayette St., New York, NY 10012 (212)473-8933

National satellite network promoting independent video

Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, 175 Fifth Avenue, Suite 2245, New York, NY 10010 (212)633-6700; fax: (212)727-7668

Media watch-dog group offering criticism to correct bias and imbalance; publishes a monthly magazine, Extra! ($241 year); sells Unreliable Sources: A Guide to Detecting Bias in News Media by Martin A. Lee and Solomon are available for lectures and workshops

Rochelle Lefkowitz and Bob Schaeffer, "How to Use the Media," in Grassroots Fundraising Journal, December 1985

An excellent summary of the elements of a media campaign

Jene F. Levey, If You Want Air Time

How to get radio or television coverage. $3 from National Association of Broadcasters, 1771 N Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036 (800)368-5644

Media Action Research Center, 475 Riverside Drive, Suite 1901, New York, NY 10115, (212)865-6690

Publishes Television Awareness Training: The Viewer's Guide for Family and Community ($6 for shipping and handling) and conducts worships on understanding how TV programs and commercial affect behavior and attitudes

Media Alliance, Fort Mason, Building D, San Francisco, CA 94123 (415)441-2557

A member-based organization that holds media activist forums and panel discussions on censorship and under-reporting in the Bay Area; publishes Propaganda Review maganize ($2014 issues); to order, write or call (707)882-1884

Media Network, 39 West 14th St., Suite 403, New York, NY 10011 (212)929-2663

Media clearinghouse; publishes Immediate Impact and guides on social issues

Pacifica Radio News, 700 H St., NW, Suite 3, Washington, DC 20001 (202)783-1620

Supplies news t the five Pacifica radio stations, as well as to several dozen other subscribing stations

Paper Tiger TV, 339 Lafayette St., New York, NY 10012 (212)420-9045

Clearinghouse for videos critiquing and analyzing mainstream media; videos are available for rental or sale

Project Censored, c/o Carl Jensen, Sonoma State University, Rohert Park, CA 948928

A national panel chooses the 10 most under-reported stories each year; contact the project for more information or to make a nomination.

Public Media Center, 466 Green Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, CA 84133 (415)434-1403

Provides advocacy advertising for non-profit organizations

Charlotte Ryan, Prime Time Activism: Media Strategies for Grassroots Organizing (South End Press, 1991) $12

Safe Energy Communications Council 1717 Massachusetts Ave., NW LL215, Washington, DC 20036 (202)483-8491

Conducts media workshops on building support for enviornmentally and economically sound energy options; the "Media Skills Manual" from the worships is available for $17.50.

John Ullmann and Steve Honeyman, eds., Reporter's Handbok: An Investigator's Guide to Documents and Techniques (St. Martin's Press, 1991, 2nd edition) $21.35

A guide to research from Investigative Reporters and Editors.

Z Radio 150 West Canton St., Boston, MA 02118 (617)247-3179

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.