By Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey)

Two-Spirit community organizer Miko Thomas (Chickasaw), also known by her stage name, Landa Lakes, is originally from Oklahoma but has been based in San Francisco for decades. Lakes serves as a board member of the Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits (BAAITS), a community-based volunteer organization offering culturally relevant activities for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex Native Americans, and she has served as a judge on many drag pageants. Lakes and her drag troupe, Brush Arbor Gurlz, perform nationwide, utilizing drag shows to raise funds and awareness for Native and 2SLGBTQ+ communities. Phoebe Farris recently spoke to Lakes at the Indigenous Media Conference organized by the Indigenous Journalists Association in July 2024.

Phoebe Farris: Landa, you are well known as a performer and entertainer and Two-Spirit activist in the Bay Area. You are co-founder of the first public Two-Spirit powwow at Fort Mason in San Francisco and the founder of the annual Weaving Spirits Two-Spirit Performance Festival and the Brush Arbor Gurlz. At this year’s Indigenous Media Conference in Oklahoma City, you were the featured performance artist for the opening night reception.

My first interaction with you was during your last performance as you moved among the audience and left the room, which had become totally silent. Earlier that day, the documentary “Sugarcane” was screened, co-directed by Julian Brave NoiseCat (Canim Lake Band Tsq'escen) and Emily Kassie. The film investigated sexual and physical abuse and infanticide at St. Joseph’s Mission School near the Sugarcane Reserve in British Columbia, Canada. Prior to your performance, had you seen the film or discussed with the directors how to create a performance that referenced issues covered in “Sugarcane”? Or was it coincidence or serendipity, or perhaps something more connected to the universe?

Landa Lakes: I didn’t know “Sugarcane” was showing, so I guess it was somehow connected to the universe, or maybe boarding schools bind us as Indigenous people. My father and two of his sisters attended Sequoyah, and his youngest sister attended Chilocco. My grandmother attended Bloomfield Academy, and my great-grandfather went to the Burney Academy, known as the 'Chickasaw Orphan Home' and 'Manual Labor School.'

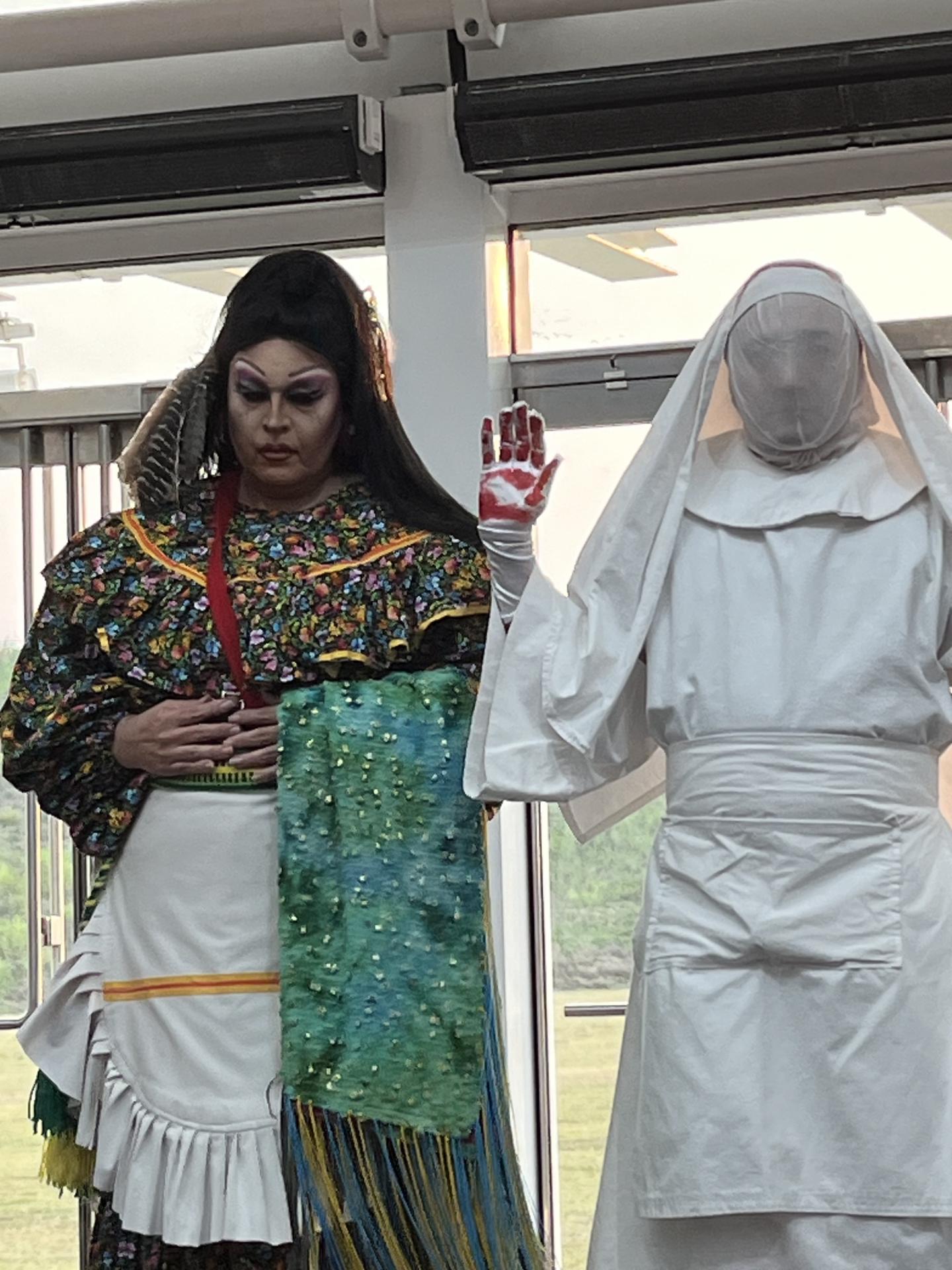

PF: In that scene, a nun enters holding a box she places on the floor. You enter wearing Indigenous clothing and kneeling with the nun, and then both of you stand and her hands are bloodied as she exits. You open the box of numbered paper dolls and roll them into the shape of an infant, which you wrap in a blanket.

LL: I think some Southeastern Tribes will recognize the box as shaped like a house. These are called ‘Grave Houses,’ or ‘Death Houses,’ and are placed within four days of burial over a grave. It’s an old tradition that is starting to fade away, but I appreciate how the audience can see it as either a Grave House or a boarding school.

PF: How do you prepare your mind and body for performances like this that deal with the raw emotions of overwhelming grief while also creating other scenes that have audiences laughing, all in one setting?

LL: Back in the 1980s, there was a project called EIC [Explorations In Creativity] where I met Mary Ann Brittan (Choctaw/Caddo). It brought in Native kids from all across the continental U.S. and Alaska to Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, OK during the summer. Mary Ann ran the drama group and introduced us to Indigenous theater from Tulsa’s American Indian Theatre Company and the writings of Hanay Geiogamah. It taught me that humor and depth are indeed siblings, and if I am giving you something serious, the humor helps to ease the mind.

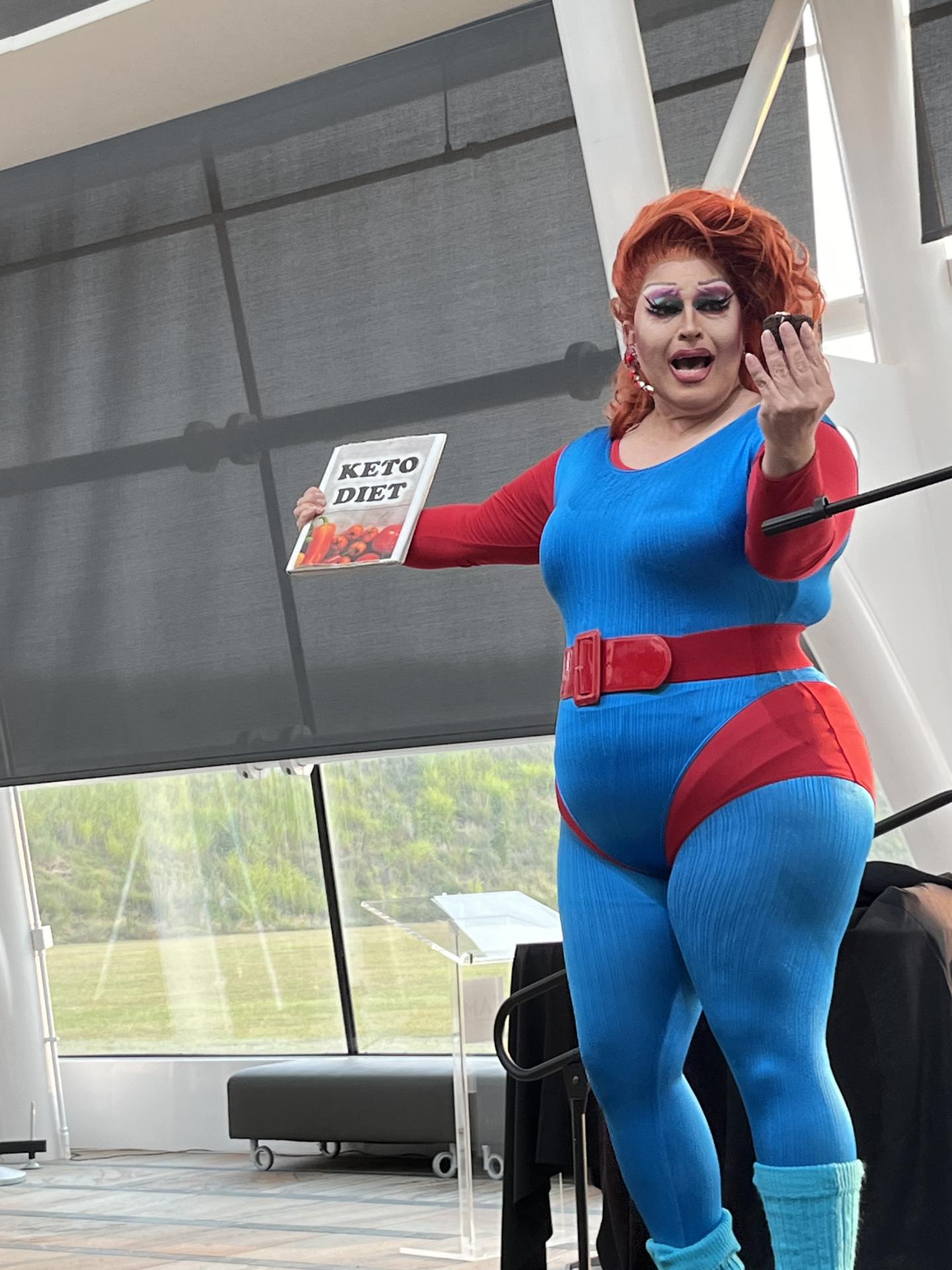

PF: Let’s go back and focus on some of your lighter, humorous scenes, such as you entering the stage in a red evening gown singing lyrics from “I will always love you” and holding a sign labeled ‘CARBS,’ then stripping down to a Marvel-inspired Superwoman outfit and doing jumping jacks while holding a book titled ‘KETO DIET.’ Please share with our readers the process for creating this skit.

LL: I am showing my age here. I am dressed in 1980s Jane Fonda workout wear. I have been doing this number since around 2005. I did it for a drag night called Duck and Cover, which was a night of cover songs. My weight is a yoyo; I am thinner and fuller depending on when you catch me. I originally did it as Atkins, but now the rage is Keto, both of which are restrictive carb diets. So putting my real struggle on stage and getting to eat a cupcake for art is fantastic.

PF: On the floor near the stage, a huge screen features close-up images of your face and hair wrapped in colorful plastic yarn that slowly unravels as you sing the lyrics to “Tapestry” and “A Coat of Many Colors.” As that scene fades, the next black-and-white image includes Indian children praying and singing, ‘John Brown had a little Indian boy, one little Indian boy.’ Can you explain the significance of these evolving images?

LL: This is from my piece, “Paper Indians.” It starts out with the message: ‘Today’s presentation has been brought to you by the Civilization Act of 1819.’ The images change between Indian children and a tutorial on how to make paper dolls—or, in my mind, how to assimilate children. When wars were done, when the buffalo were gone, when the people were removed and restricted, it came natural to Congress to take away children. Ultimately, it is this act of Congress that gave money for these schools and religious institutions to take the Indigenous people out of the so-called savagery and assimilate them into the larger society, and it has played out again and again in different ways in things like the Indian Relocation Act. In my opinion, many of these acts have been very destructive to Indigenous families, and the boarding school system was one of the worst.

PF: People of my generation grew up using Land O’ Lakes butter with the beautiful Indian maiden featured on the packaging. It was the most popular butter. Please tell us how you took back the icon, changing your name to Landa Lakes and properly Indigenizing it.

LL: My original drag name was Autumn Westbrook when I started performing at The Wreck Room in Oklahoma City in the 1980s. Around 2004, I wanted to revamp my performance style because it had changed and was more about stories, and I wanted something that was tongue-in-cheek and recognizably Indigenous. Everyone knew Mia (the Land O’ Lakes Indian Mascot), and although the artist that had created the final version of Mia was Indigenous, I just don’t agree with Indigenous bodies being used for mascots by non-Indigenous folks or [in a way] that doesn’t benefit a Nation that is being used. There was a time when we had little to no representation, so I think some of the generations before me were proud of things like the Redskins, Cher in a headdress. I even wanted to be the Indian in the Village People back in the ‘70s. But now we have real representation, and I don’t think we need to slide backward into being a tool to convey Americana.

PF: Please share with us how your Chickasaw Nation heritage, childhood in Oklahoma, your identity as Two-Spirit, engagement in social justice activism, and your career in performance art all intersect so smoothly to outsiders. What are the challenges to positively embracing all of these aspects of your life and becoming the powerful Indigenous person that you are?

LL: I grew up in the Tupelo-Stonewall, Oklahoma, area. We were always surrounded by our family. My family started a small dance troupe called the Buck Creek Dancers, and we learned some songs and dances from Buster Ned, who led the Chickasaw Choctaw Cultural Committee and Dance Troupe. Buster grew up with my grandfather, Buck Thomas, when Buster’s grandmother married my great-grandfather, Rev. Robert Bob Thomas. So, I think culturally, I grew up with a steady mix of Christianity and tradition. I would say my activism really started at Oklahoma University in Norman as a part of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance. I was also a part of the American Indian Student Association. But for me, the real activist work was within the GLA. My friend and fellow Choctaw activist, Ben Carnes, really encouraged me to work for things that were important for future generations, and I feel I have tried to accomplish that outside of performance, but also to incorporate issues within performance that reach an audience that may have no idea about the Indigenous world.

PF: Thank you Landa, Megwich.

Follow Landa Lakes on Instagram at @landalakes.

--Phoebe Mills Farris, Ph.D. (Powhatan-Pamunkey) is a Purdue University Professor emerita, photographer, and freelance art critic.