By Laura R. Graham, Edson Krenak, and Linda Rabben

In October 2020, months after A’uwẽ-Xavante leader Hiparidi Top’tiro received hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) as a treatment for COVID-19 in Mato Grosso, Brazil, the Washington Post revealed that White House officials had circumvented FDA regulations to distribute millions of doses of the drug in both the United States and Brazil.

Top’tiro recovered but only learned he had received the drug after it was administered. The A’uwẽ-Xavante leader, who has spoken at the United Nations in New York and Geneva about Brazil's failure to respect Indigenous rights, reported he would have refused HCQ had he known it was neither safe nor effective. “My heart was racing and I was afraid,” he said. The World Health Organization (WHO) discourages the use of HCQ in the treatment of COVID-19, either alone or in combination with other drugs. But the Brazilian government has administered it to thousands of Indigenous people in the country.

Hiparidi is one of hundreds of Indigenous people in Brazil who have contracted COVID-19. To date, some 821 A’uwẽ-Xavante have contracted the virus, which has claimed 44 A’uwẽ-Xavante lives, more than six in one community within a single 24-hour period. A’uwẽ-Xavante are just one of Brazil’s 305 Indigenous nations. Although they rank 13th among Indigenous Peoples for the number of confirmed cases, according to Brazil’s Special Indigenous Health Service (SESAI), A’uwẽ-Xavante have the second highest COVID-19 fatality rate of any ethnic group in Brazil. The A’uwẽ-Xavante morbidity rate is 11.7 percent, 160 percent higher than the national average. The number of Indigenous infections is five times higher than the Brazilian national average.

Across Brazil, as of November 3, SESAI- reported the number of Indigenous COVID-19 cases at 32,746. This number excludes Indigenous people who live in cities and towns, because SESAI does not count or treat urban Indians. The number of Indigenous deaths has reached 478. Data collected by Brazil’s Articulation of Indigenous Peoples (APIB) indicates higher totals, with 38,646 confirmed cases and 870 Indigenous fatalities as of November 4. Reported Brazilian cases totaled over 5,675,032, with 162,628 deaths.

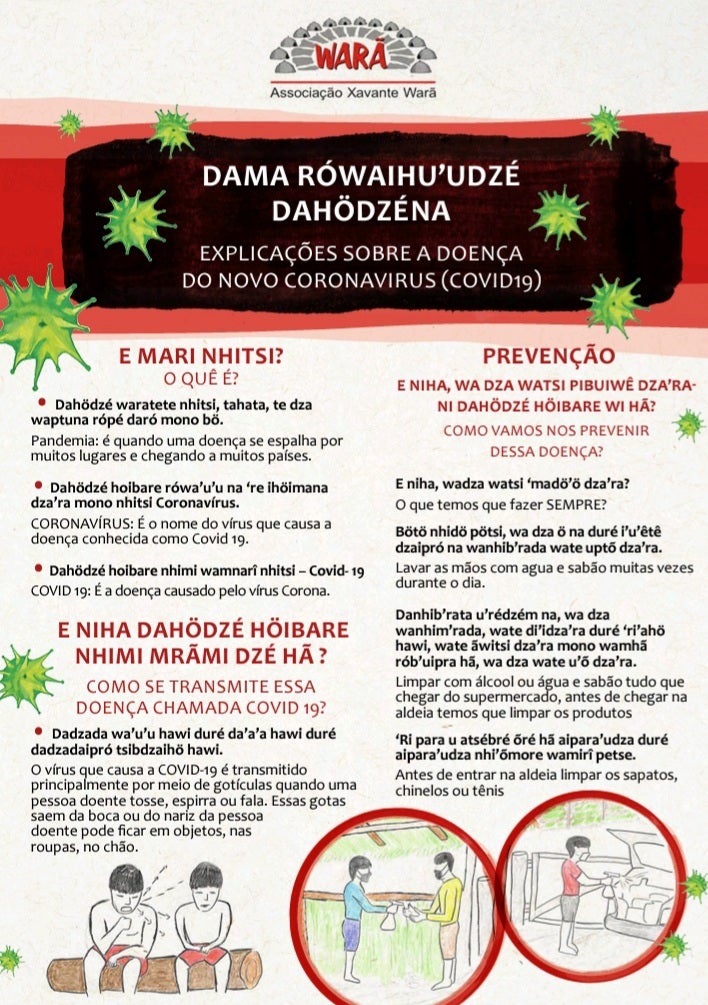

Xavante COVID-19 prevention poster. Courtesy of Xavante Warã Association, 2020.

According to APIB, Indigenous people are dying at a rate nearly twice the national average. By failing to prevent COVID-19’s spread into Indigenous communities, the Brazilian government is neglecting its constitutional and international obligations to protect the health and safety of Indigenous Peoples.

As anthropologists studying Indigenous communities, we are alarmed that doctors and officials from SESAI and the Brazilian military (responsible for the delivery of aid) have recommended almost indiscriminate use of various drugs to treat Indigenous COVID-19 patients. Our reliable sources have seen doctors give these drugs to “calm,” instead of treat, Indigenous patients; then they send patients back to their villages without proper follow-up.

The prescribed medications are mainly chloroquine and HCQ — the Bolsonaro government’s “magic bullets” — even though scientific studies cast doubt on their efficacy. Worse still, in elevated dosages, these drugs have contributed to the deaths of many patients, especially elderly ones. Older Indigenous people, including leaders, shamans and teachers who are the communities’ living libraries, have died of COVID-19.

Domingos Mahör̵ö, an elder from the same Indigenous Territory as Hiparidi Top’tiro, was treated in the same hospital at the same time. He died of a heart attack on July 6. HCQ might have brought about Mahörö’s death.

Meanwhile, the U.S. State Department boasted in late May that it had sent two million doses of HCQ to Brazil. It also announced “a joint United States-Brazilian research effort [to] include randomized controlled clinical trials. These trials will help further evaluate the [drug’s] safety and efficacy for both prophylaxis and the early treatment of the coronavirus.” Since April, weeks before the U.S. government sent the drug to Brazil, international researchers suspended or stopped clinical trials of HCQ, because the drug apparently contributed to heart arrhythmias and deaths of COVID-19 patients or was shown to be ineffective. A clinical trial of HCQ in Manaus, the largest city in the Brazilian Amazon, stopped in April after 11 out of 81 participants died.

According to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, “No one shall be subjected without his free consent to medical or scientific experimentation.” Indigenous people are often excluded from clinical trials because they might not speak or understand the language of the informed consent agreement. Nevertheless, health workers report that the Brazilian government is giving HCQ to Indigenous people in both rural and urban areas, despite the lack of proof of the drug’s efficacy and its known hazards.

Despite the presence of tens of thousands of Indigenous people in the Manaus area, the Brazilian government refuses to classify them as Indigenous. It limits its responsibility to provide appropriate medical attention, as mandated by the Brazilian Constitution and international law, only to Indigenous people who live in villages or reserves in remote areas. But Indigenous people do not “become white,” as the Secretary of Indigenous Health has suggested, simply by residing in cities and towns.

Brazilian military teams have violated Indigenous people’s human rights by entering their territories without residents’ permission and foisting chloroquine or HCQ on them without their consent, according to reliable independent sources. As a result, Indigenous leaders and their Brazilian allies have accused the government of genocide.

COVID has incited racist sentiments in eastern Mato Grosso, and Bolsonaro’s anti-indigenous stance has exacerbated them. Demeaning, racist WhatsApp messages, allegedly sent to Xavante and Bororo by merchants as well as regional politicians who are antagonistic to Indigenous people, blame them for the high incidence of COVID-19 in the region. Xavante leaders have presented these messages to the Federal Public Defender, and an investigation is underway.

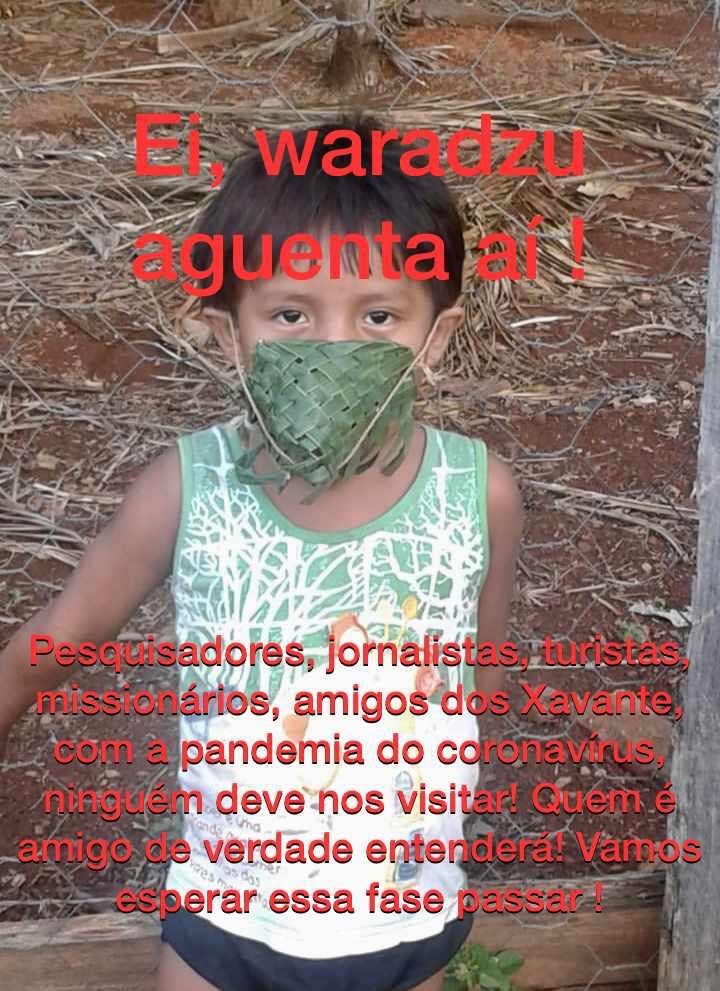

Meme by AnonFeb2020: “Hey, white people, hang in there! Researchers, journalists, turists, missionaries, friends of Xavante, no one should visit us! True friends will understand! We are waiting for this to pass!”

In the current political climate, the government’s failure to provide Indigenous people proper medical attention and protect them from intrusions by loggers, miners, poachers, missionaries, and even military medical teams who could be infected with the virus, looks like lethal malfeasance.

The National Confederation of Health Workers asked a Brazilian Supreme Court justice in early July to stop the production, supply and prescription of HCQ and chloroquine for Brazilian COVID-19 patients. The health workers claimed that government support for the drugs “contradicts scientific, technical and sanitation guidelines of national and international authorities.”

Yet Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro continues to promote HCQ. After testing positive for COVID-19 himself, the president announced that he was taking the drug. Meanwhile the Brazilian public-health system nears collapse as thousands of vulnerable people, including Indigenous people, are dying of COVID-19.

President Bolsonaro’s recommendations regarding the use of HCQ prompted the resignations of two state health ministers, Luiz Henrique Mandetta and Nelson Teich , who both opposed the drug’s distribution and use. Following their resignations, the production of HCQ increased in Brazil, and the drug continued to be recommended for treatment of COVID-19, even in patients with mild symptoms.

Brazil’s current health minister is an army general with no public-health qualifications. President Jair Bolsonaro, who has touted HCQ as a cure for COVID-19 and praised the military dictatorship that controlled Brazil from 1964 to 1985, has packed the health ministry with dozens of military personnel.

After numerous studies conducted outside Brazil and strong evidence disproving the drug’s efficacy as a COVID-19 treatment, the Brazilian government paused production. However, with stockpiles full, the federal government has continued to encourage states and municipalities to promote HCQ for the treatment of COVID-19. Some states, such as Maranhão, received over 80,000 doses. Maranhão’s health secretary affirms that the drug will only be used when it is recommended. Nevertheless, the federal government has not revised its recommendations concerning the use of HCQ.

Brazil must immediately implement health and safety measures that fully conform to WHO guidelines and recommendations. It must provide resources and protocols to ensure all SESAI districts and facilities implement procedures that guarantee the proper tracking and treatment of infected individuals, as well as the isolation of positive COVID-19 cases and patients undergoing treatment.

Brazil also needs to equip SESAI to set up quarantine facilities away from Indigenous residences, provide trained medical professionals to staff these facilities, increase the number of professionals attending Indigenous areas and urban environments, supply proper personal protective equipment (PPE) to health professionals working with Indigenous Peoples and in quarantine facilities, and supply Indigenous communities with PPE and disinfecting supplies so they may follow sanitation guidelines.

The government must institute regular and repeated COVID-19 testing of the Indigenous population at their request and with their informed consent, as well as increase the number of Indigenous health clinics dedicated specifically to the pandemic.

Finally, the government must cease the administration of HCQ to Indigenous patients wherever they live, either as a prophylactic agent or treatment of COVID-19, unless it is closely monitored in clinical trials and hospital settings and with patients’ informed consent. Indigenous patients must never be used as research subjects in clinical trials without such consent, as mandated by international law.

-- Laura R. Graham is president-elect of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America and Professor of Anthropology at the University of Iowa and a Cultural Survival Board Member. Edson Krenak (Krenak) is completing a PhD in Anthropology at the University of Vienna, Austria. Linda Rabben is an Associate Research Professor of Anthropology at the University of Maryland.