By Dev Kumar Sunuwar

The 2019 Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) was passed by the parliament of India on December 11, 2019, amending its existing Citizenship Act of 1955, and causing violent protests throughout the country. The protests were seen mostly in India’s northeast regions, particularly in Assam and Tripura, home to more than 230 different Indigenous Peoples. India’s northeast seven states share borders with Bangladesh, Myanmar (also known as Burma) and China.

Through the new Citizenship Amendment Bill, Indian Citizenship is granted to illegal migrants from neighboring countries—Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan, which some Indigenous Peoples fear that the law would make them a minority in their homelands. According to them, with ill intention, the government of India through CAB wants to wipe out their histories, cultures, languages, and identities. Therefore, millions of people took to the streets against the Bill.

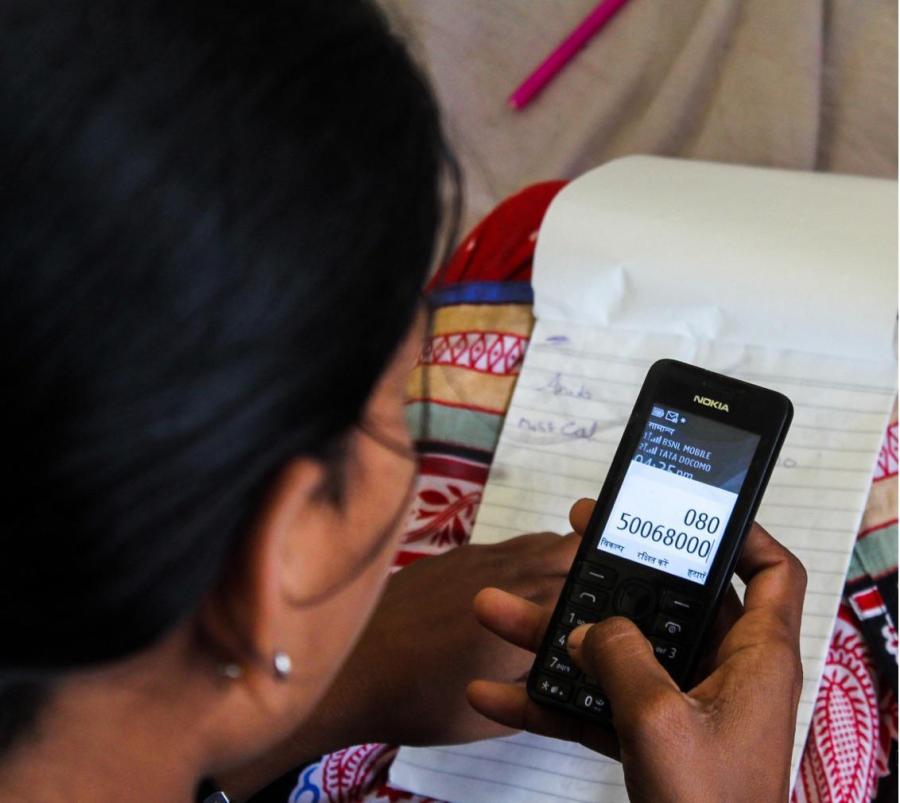

Protesters are demanding the recall of the amended Citizenship Amendment Bill. Many torched vehicles, disrupted rail, road, and air services in Assam, Tripura, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh. There were frequent clashes between police and protesters, injuries including killings. To quell tension, Indian authorities shut down mobile and internet connections and called on army personnel to restore order and imposed a curfew.

“The government of India introduced the Bill without any proper consultations with concerned representatives and without a study of the impact,” said Ken Timung Arleng, young Indigenous rights activist at Diphu Assam in a conversation with Cultural Survival. “The Citizenship Amendment Bill is likely to curtail the continuity of languages, cultures including economic well-being of the Indigenous Peoples of Assam and the northeast.”

“If the government of India grants citizenship to foreign immigrants, irrespective of religion, race, or culture, it will cause effects not only on the political rights, but also the cultural and land rights of the majority of Indigenous populations in Assam as the law motivates more migration from foreign countries,” says, D. S. Lekhthe, a lawyer from Assam. “Assamese view that the recently enacted Citizenship Amendment Bill will adversely impact the people of Assam and the northeast most.”

The new law allows migrants who arrived in India before 2014 to become citizens. In Assam, the biggest state in the northeast, ongoing tensions have been going on for years between Assamese speakers and Bengali-speaking migrants who have crossed a porous border with Bangladesh.

Following the massive protests and flow of news that Citizenship Amendment Bill discriminates against Muslims, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) held a press briefing on India outlining their concerns about the new law, stating that it is “fundamentally discriminatory in nature” and that “OHCHR hopes the Supreme Court of India will consider carefully the compatibility of the law with India’s international human Rights obligations.”

Agitators continue their protest across northeast, demanding the implementation of the 1985 Assam Accord, with which the newly passed Bill conflicts. The 1985 Accord states foreigners who entered Assam before March 25, 1971 were to be given citizenship and rest had to be expelled. The amended Bill shifts the cut-off date to December 2014 from December 1951 as the date of detection and deportation and also creates a National Register of Citizens (NRC). In order to conduct a census in 2021, the government of India is planning to collect data for the National Population Register (NPR) in 2020 to create a NRC afterward to identify illegal immigrants across the country. In 1951, a National Register of Citizens in Assam was created to determine who was born in the state before March 24, 1971. The final version of the list unveiled recently strips approximately 1.9 million people in Assam (which borders Bangladesh) of citizenship of those who declared themselves as foreigners. This is also likely impact Bangladesh, as there maybe potential influx of immigrants from India. Bangladesh is already grappling with over 900,000 Rohigya refugees from Myanmar, who are unlikely to be repatriated.

Following the massive protests which took place for six years beginning in 1979, led by the All Assam Students Union (AASU) based on the issues that foreigners—mainly Bangladeshis—were included on voter lists, in 1985, the government of India agreed to the Assam Accord comprising of 15 clauses. Clause 5 of the Accord deals with the issue of foreigners, their detection, the deletion of their names from the voter lists, and their deportation through practical means. The clause states, “all persons who came to Assam prior to 1 January 1966, including those amongst them whose name appeared on the electoral rolls used in 1967 elections, shall be regularized,” meaning illegal immigrants who entered Assam before December 31, 1965 were to be granted citizenship with voting rights immediately.

Clause 5 also further states, “foreigners who came to Assam after 1 January 1966 and up to 24 March 1971 shall be detected in accordance with the provisions of the Foreign Act, 1946 and the Foreigners (Tribunals) order 1964.” This meant immigrants who came to Assam between 1966 and March 24, 1971 were to be disqualified and had to get registered themselves as “foreigners” in accordance with the Registration of Foreign Act 1939.

The Citizenship Amendment Bill shifts the cut-off date for granting citizenship from March 24, 1971 to December 31, 2014. The protestors argue that this move is going back on the government’s promise made to protect the cultural identities of Assamese and the northeast region. Another provision challenged during the protests is clause 6 of the Accord, which states, “the constitutional, legislative and administrative steps will be taken by the Center to protect, preserve and promote the cultural, social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people.”

“I want to assure my brothers and sisters of Assam that they have nothing to worry after the passing of CAB”, said Narrendra Modi, Prime Minister of India on Twit trying to calm the fury in the northeast. “I want to assure them—no one takes away your rights, unique identity and beautiful culture. It will continue to flourish and grow."

Activists view that there were flaws in the procedural laws and non-implementation of the obligations set forth in the Accord. Sanaton Laishram, a human rights activist from Manipur says, “There is a contradiction between safeguarding culture, identity, including political rights of iIndigenous Peoples of the northeast and CAB, including with NRC. Thus there is a clear need to conduct a study on the effect of the law beforehand and to hold dialogue meaningfully across concerned populations who fear that their culture and identity will be submerged.”

The Supreme Court of India has slated to hear the dozens of petitions filed to review Citizenship Amendment Bill on January 22, 2020.

Photo by Rita Willaert.