By Adriana Hernández (Maya K’iche’, CS Staff)

In Guatemala, inequalities have deepened and have become more evident due to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the lack of adequate and timely vaccine distribution. Getting a vaccine in Guatemala means long hours of waiting in lines, months of waiting for an appointment, crossing the border to Mexico, or traveling to the United States or other countries just to get vaccinated. According to the Laboratorio de Datos (Data Laboratory) Research Center, at the pace the government is distributing the vaccines, it will take about ten years for all of Guatemala’s population, almost 18 million people, to be fully vaccinated.

COVID-19 has made pre-existing socioeconomic inequalities more evident. Economic, ethnic, social disparities have strongly affected Indigenous Peoples living in remote areas for many years. Data Laboratory data shows that vaccines against COVID-19 have been distributed mainly in urban areas such as the departments of Guatemala City with 43 percent of Indigenous population and Quetzaltenango with 65 percent of Indigenous population. From the total of 1,079,800 vaccinated people as of June 21, 2021, 13 percent of the vaccines were distributed in Guatemala City, and 8.8 percent in Quetzaltenango. Also, data shows evidence of the large gap for Indigenous communities in accessing the vaccine. This data reveals that more vaccines should have been available to Quiche, as it is one of the five provinces with the highest populations in the country, and 90 percent of its inhabitants are Indigenous. Additionally, departments (provinces) of Totonicapan and Solola, with 97 percent Indigenous Peoples, have only accessed 5 percent of the vaccines from the total vaccines distributed in Guatemala City.

Source: Laboratorio de Datos Guatemala. The vertical axis represents the number of vaccines distributed. The horizontal axis represents where the government distributed the vaccines.

A Distant and Endless Wait for Indigenous Communities

One of the raised concerns is how the government has distributed the vaccines and their communications strategy throughout the vaccination campaign. In a country with the most significant disparities in Latin America, where only 21 percent of the population have access to laptops, and 29 percent have access to the internet, registering through a website to get an appointment is a distant and complicated task for Indigenous communities.

This graphic reveals how the distribution of vaccines has left out Indigenous communities as of July 22, 2021. The lack of internet access, materials in Indigenous languages, and misinformation circulating are causing less desire to get vaccinated.

Source: data extracted from Laboratorio de Datos Guatemala

Crossing Borders to Get Vaccinated

Vilma (Maya K’iche) is a single mother living in an urban area of Quetzaltenango. She is the mother of five children and is worried about getting sick and not working to sustain her family. In May, she decided to travel with her 20-year-old daughter to Tapachula, Mexico, but her daughter did not have the credentials required by the Mexican government to get vaccinated. They both ended up spending two nights in detention. “We intended to get the vaccine since our government system is moving slowly, and it seems like young people will not have access to the vaccine ever. We care about our families, and the wait is endless,” she said. Vilma and her daughter mentioned that they saw people from different provinces in Guatemala during the two nights in detention, but not too many people from Guatemala City. She and her daughter witnessed people attempting to get a vaccine by crossing the border via boats.

Angelica, a 25-year-old non-Indigenous woman living in Guatemala City, and her family traveled to New York City to get vaccinated in June. She expressed her concern about how long the Guatemalan government is taking to provide vaccines. Angelica and her family have a valid visa to travel to the United States and can afford a round trip ticket to get their two doses of Moderna vaccine. She expressed how much relief she felt after getting vaccinated.

Migration regulations create more challenges to the full ability of Indigenous Peoples’ to travel. In US regulations, the cost of a B1/B2 visa for a temporary visitor, USD 160, represents a little less than the monthly salary for farming in Guatemala, as the wage is approximately USD 12 per day. Before the pandemic, I remember the time and preparation it takes to fill out the forms and being nervous about filling out the necessary paperwork in another language that was not my native language. During the interview, I remember an Indigenous woman in line getting ready for her interview. When it was her turn to speak, language barriers came across, not only by the applicant but also from the consular officer’s side, who spoke in her second language. The interview lasted less than two minutes, and it seemed like the applicant could not clearly understand the question she was asked; then, the visa was immediately denied.

Internet Access’ Role in Obtaining the Vaccine

Staying informed about the vaccination campaign is more accessible if you are on social media and have internet access. An Indigenous family that wishes to stay anonymous that lives in the urban area of Quetzaltenango heard rumors on social media about people over 40 years old getting the vaccine the same day. The process did not require registration and the vaccine was available only by showing an ID. Immediately, this family went to get the vaccine and waited less than one hour to get it. It is such a relief for them now, but the problem is that not everyone has access to this type of information. Only those who live in the urban areas, with access to the internet, and fast modes of transport to travel to the vaccination center, can get their doses.

What happens to those who do not have access to the internet or have Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or other social media accounts? When will women who are caretakers for their children be able to receive their doses? Elders who understand Spanish as a second language also encounter technical issues when registering their IDs and personal information through a website. There is a combination of misinformation and how the information reaches the communities, including access outside urban areas, government bureaucracy, distrust, and fear towards the government. That all contributes to high levels of COVID-19 infections and low levels of vaccinations in Guatemala.

The governments should engage Indigenous groups to face the pandemic to ensure that the registration process steps are accessible in Indigenous languages. If more Indigenous groups are involved in the decision-making process of the campaign against the COVID-19, there will be more awareness of the needs of the communities. The goal should be the massive spread of accurate information in the 22 Mayan, Garífuna, and Xinca languages that exist in the country, not only via the internet but through community radio and other means of communication that can be accessed in remote areas.

Indigenous Communities are Disproportionately Impacted by COVID-19

This pandemic disproportionately impacts Indigenous Peoples. While people in urban areas can get the vaccine and buy sanitizers, masks and wash their hands constantly, the other part of the population, primarily Indigenous, lack access to running or even purified water.

Indigenous businesses have also been dramatically affected by this pandemic. Indigenous Peoples are experiencing difficulties when accessing transportation to bring their products to the markets. The cost of public transport has increased as the buses are operating at 50 percent of their capacity.

In terms of community and families, Indigenous Peoples have experienced losses, especially the premature deaths of Elders, knowledge keepers, healers, spiritual guides, and midwives. The loss of Indigenous leaders who have dedicated their lives to stewarding traditional medicine and protecting biodiversity produces devastating short and long-term effects in and for communities.

The fear and distrust from the communities are embedded not only in the current events of the pandemic but are deeply rooted in the history of violence that Indigenous Peoples faced during the genocide in the 1980s, where around 90 percent of the Ixil villages were scorched and people were massacred. The personnel of the Ministry of Health in Guatemala is encountering barriers to providing vaccines to communities in Quiche. Jose Raymundo, a nurse, working in Nebaj, Quiche, says, “People often reject vaccines because they think that the government sent us and that the government has paid us to kill them.”

Inequitable Share of Vaccines Globally

While some countries are strategically considering a booster, other countries like Guatemala, are struggling to vaccinate 2.4 percent of the population, as of August 2021. Duke University’s Global Health Innovation Center research found that high-income countries could secure 53 percent of the near-term vaccine supply. This data revealed that the world’s lowest-income countries (92 countries), including Guatemala, will not reach a vaccine rate of 60 percent of their population until 2023 or years later.

Additionally to the socioeconomic disparities among countries, there are gender inequalities that have become more evident due to the pandemic. Women, representing most health workers and caregivers, are on the frontlines of the pandemic. In addition to dealing with the virus itself, women have been drastically affected by being forced to leave jobs to meet family responsibilities. Also, women-owned businesses have been affected, forcing them to close their doors, which in turn affects the economic sovereignty of families and communities.

Solutions for and by Indigenous Peoples

Despite the terrible effects that pandemics have brought to the Americas historically- smallpox, measles, and yellow fever- Indigenous Peoples have demonstrated the strength and resilience of their communities over time. Indigenous Peoples continue nourishing their immune systems by producing traditional foods, cultivating seeds, and using medicinal herbs to prepare infusions to boost immunity. The practice of therapeutic baths and other immune-boosting and preventative practices are still being practiced today as we wait for an unknown answer about when the vaccine will be available.

Culturally and linguistically relevant information for Indigenous communities is missing in the government’s communication strategy. In a country where almost half of the population is Indigenous, it is crucial to prioritize where the needs are and effectively communicate reliable information for Indigenous Peoples in the Indigenous languages of Guatemala. Community media, including community radios, have and continue to be powerful tools for Indigenous communities to access information in Indigenous languages. It is essential to put all the tools available for the use of Indigenous Peoples.

Community radio is a low-cost tool. Indigenous communities use it to defend their cultures, rights, lands, and natural resources. Even in the communities where there is no electricity or power outages are very common, people can afford a battery-powered radio. It is vital to disseminate information orally through community radio, considering that almost 19 percent of the Guatemalan population cannot read or write. Also, important messages broadcasted through mainstream media do not reach the audience that speaks only an Indigenous language, especially Elders.

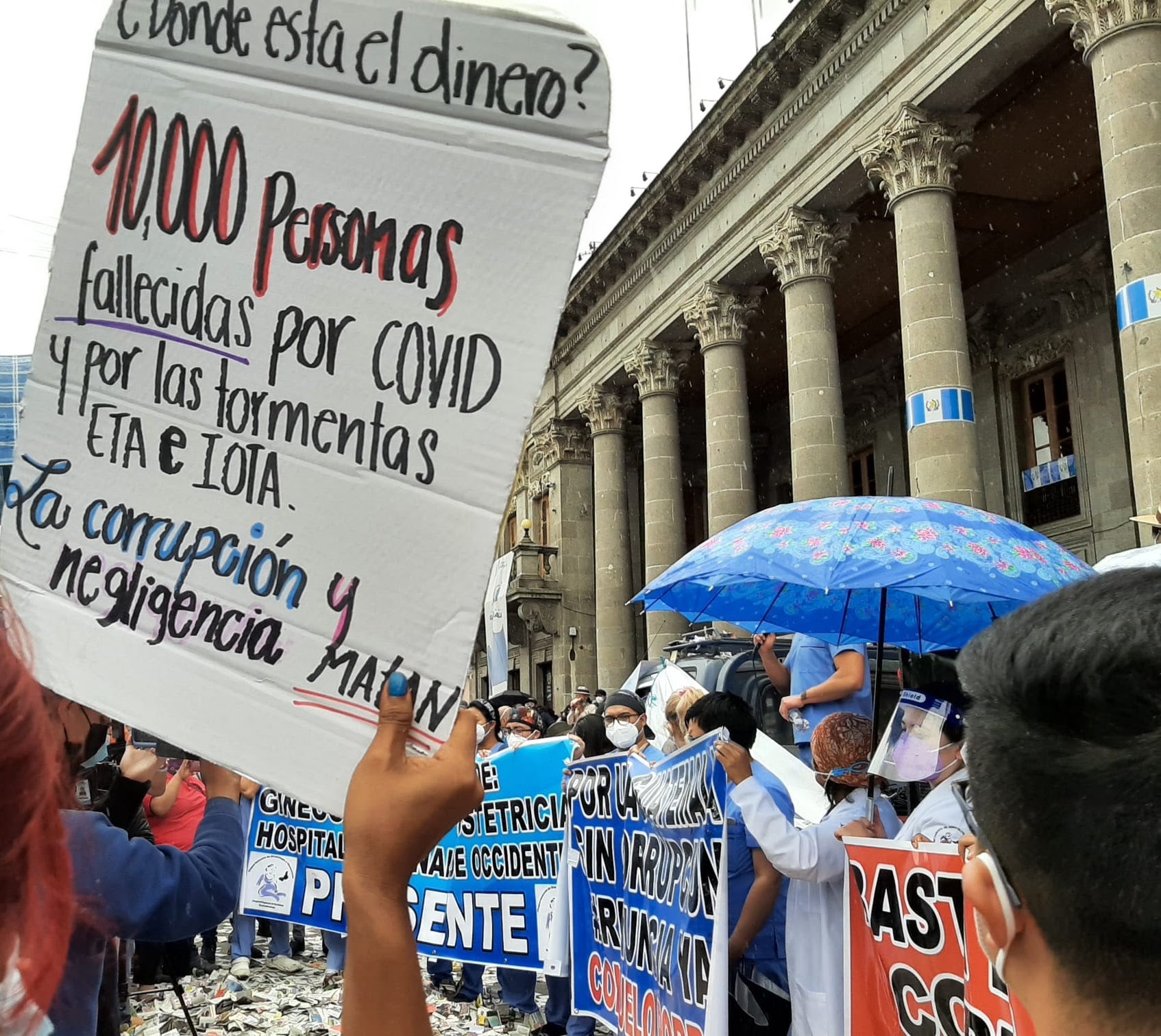

It is important to act together and support Indigenous-led efforts to face this crisis. It is critical to support their grassroots efforts in distributing reliable information, conducting massive campaigns, promoting traditional medicine, and using masks within the communities. The worst of the pandemic is not only the COVID-19 virus and its effects on health, but the crisis within the crisis, led by an unequal distribution of vaccines that will only extend the pandemic even further.