By Erika Mayer

The Amazon River Basin is a place like no other on Earth. Home to the largest rainforest in the world, it is vital for the carbon held in its forests, for its breathtaking biodiversity, and for the Indigenous Peoples who live within it. In recent years, this indescribably important region has been under siege by human development driven by both governments and corporations. One new and particularly dangerous development is a proposed South American Transcontinental Railroad that would be built from Peru to Brazil. This “Twin Ocean Railroad” is backed by the Chinese government and, once completed, would connect the two coasts of South America—cutting directly through the Amazon to do so.

Such a monumental undertaking would cost billions of dollars, but it could also bring notable economic benefits. Brazil and China are strong trade partners; in fact, in May, the Chinese Premier Li Keqiang announced that billions of dollars would be allocated to investment and trade agreements with Brazil. Peru, too, has compelling reasons to support the railroad, as it sends more exports to China than it does to any other nation. The railroad would strengthen the already strong trade between China and Latin America by greatly reducing the cost of shipping commodities to China from Peru and Brazil.

Despite its economic promise, the project would not universally benefit everyone in Brazil and Peru. The railroad would be over 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) long, and its construction would damage the delicate environment of the Amazon and affect as many as 600 Indigenous groups. Some of these Indigenous Peoples are extremely isolated and highly vulnerable to contact with outsiders who could bring disease and environmental destruction to their communities.

Due to its potential dangers, the railroad has alarmed activists and organizations working to protect the Amazon Rainforest and to defend the rights of Indigenous Peoples. One such organization, the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America (SALSA), sent letters raising concerns about the railroad to the President of Brazil, Dilma Rousseff, and the President of Peru, Ollanta Humala, dated June 30, 2015. These letters were drafted by Danish anthropologist Søren Hvalkof and signed by SALSA’s President Jonathan D. Hill. They focus on the many Indigenous people whose lives and livelihoods would be threatened by the project and urge the Brazilian and Peruvian governments to fully respect Indigenous rights at every step. SALSA has also released a statement explaining the potential impact of the railroad and the purpose of the letters, which can be read here.

The letters first outline the immense risks of the project. The transcontinental railroad would not simply mean a linear swath of trees cut down in order for tracks to be built. Such an extensive project would require a network of roads and stations, and would bring new people—including more developers, loggers, and drug traffickers—to the remote regions of the Amazon. All of these factors could cause wide-ranging and potentially disastrous consequences for the Amazon’s Indigenous Peoples.

If the railroad is to be built despite the risks, however, its impact could be lessened if its route avoids the Amazon’s most isolated, endangered regions. Out of the several routes that have been proposed, SALSA specifically advises against the most northern course. This route would run from Bayóvar of Piura, a harbor on the coast of Peru, to one of two possible ports in Brazil, either Porto do Açu or Santos. It would cut through or near the Isconahua Territorial Reservation, home to the isolated Isconahua people; Serra do Divisor National Park; and the Zona Reservada Sierra del Divisor, a proposed national park in Peru. In addition, the staggering biodiversity found in the Ucayali-Acre border zone between Peru and Brazil, a rainforest region, as well as the central Brazilian cerrado, a tropical savannah, would be in danger. When environments are threatened, so too are Indigenous Peoples, and the list of Indigenous Peoples that would be affected is long; SALSA’s statement specifically names the Shipibo-Conibo, Ashéninka, Nukini, Puyanawa, Yaminawá, A’uwẽ-Xavante, Iranxe, Nambiquara, Mammaindê, Negarote, Umutina, Pareci, Kinsede, Yualapiti and Wauja. For all of these reasons, the northern route would be particularly destructive.

Another proposed route lies further south, connecting the Brazilian coast with the port city Ica in Peru. Any railroad built through the Amazon rainforest would have negative consequences, and the southern route is no exception—it would, for example, cut through Peru’s Manú National Park, a Biosphere Reserve and UNESCO World Heritage Site. However, SALSA recommends the southern route as less harmful overall than the northern option.

Many of the risks of the railroad are already all too apparent, but much remains unknown. SALSA therefore requests that studies be conducted to determine the railroad’s potential impact—and that the results of these studies be carefully considered before decisions are made. The letters also call on the governments to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples, rights guaranteed by the ILO Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

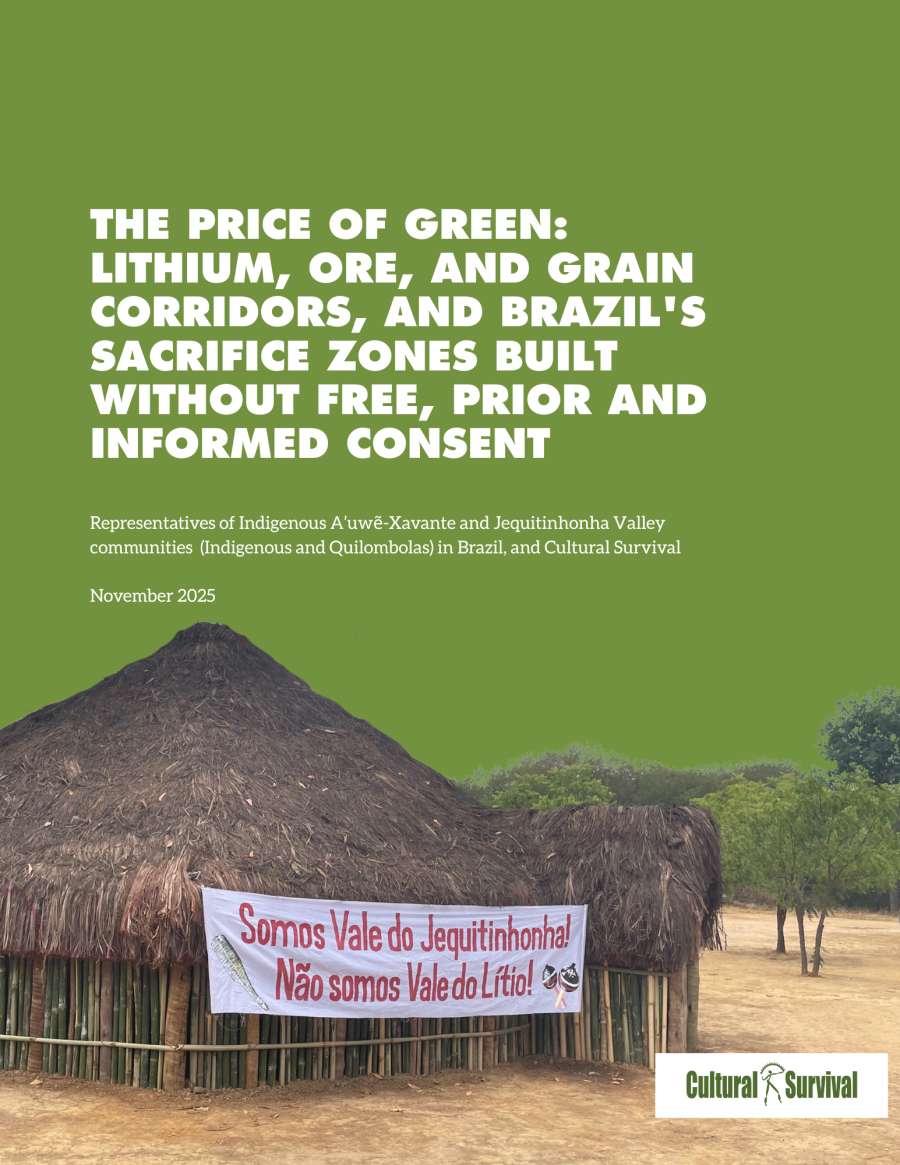

One crucial right is Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, which requires that Indigenous Peoples must be fully informed about projects on their lands and, importantly, that they decide whether or not such projects will proceed at all. Because some of the affected Indigenous Peoples are extremely isolated, implementing Free, Prior, and Informed Consent could be particularly challenging. Given these challenges, the letters ask the governments to detail exactly how FPIC will be implemented to ensure a fair and informed consultation and decision-making process.

As the railroad project becomes more than just a distant proposition, much depends on the decisions made by the governments of Peru and Brazil. The lives, cultures, languages, and societies that depend on the Amazon and its ecosystem are irreplaceable, and their voices must be heard.

SALSA’s statement: http://www.salsa-tipiti.org/news/salsa-statement-on-the-twin-ocean-railroad-26-june-2015/

Photo by Neil Palmer/CIAT for Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).