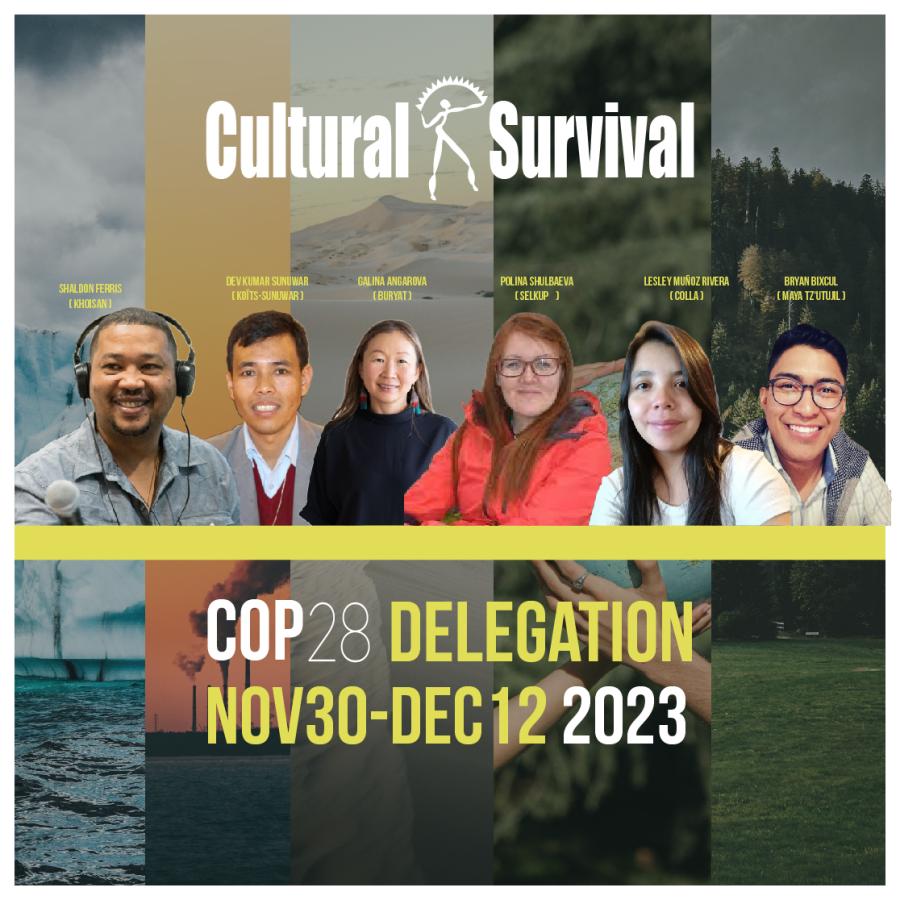

By Polina Shulbaeva (Selkup), Bryan Bixcul (Maya Tz'utujil), Edson Krenak (Krenak), CS Staff

In 2022, at the United Nations Framework on Climate Change Conference of the Parties (UNFCCC COP27) in Egypt, we saw the creation of the new Loss and Damage Fund, which is arguably one of the most consequential decisions coming out of the COPs since the Paris Agreement, though many serious questions remain about how effective it will be. We also saw parties fail to agree on phasing out fossil fuels, instead promoting carbon markets, the concept of “net zero,” and false solutions that delay real action to reduce emissions. Meanwhile, a recent report coming out of the technical dialogue of the first Global Stocktake revealed that the world is not on track to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, which are essential to prevent a worsening of the current climate crisis. Much is at stake for Indigenous Peoples in the coming climate negotiations.

In 2023, the UNFCCC COP28 will take place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, from November 30 to December 12. It is likely to be one of the toughest and most controversial negotiations on fossil fuel divestment, as it is being held under the presidency of Sultan Al Jaber, who is also CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. There has been a wave of criticism leading to COP28 from experts and politicians, and there are serious concerns that COP28 will promote the interests of the fossil fuel industry and other corporations. It is yet to be seen whether significant progress can be achieved on phasing out fossil fuels when the climate talks are being presided over by one of the largest oil and gas-producing countries in the world.

The Just Transition to the Green Economy will also be one of the main topics during the climate talks in Dubai, with discussions focused on the actions and technologies needed to achieve this. On December 5, an Indigenous Peoples' Day will be held in parallel with the Day of Energy and Industry. Cultural Survival will host events focused on the Just Transition and how securing the rights of Indigenous Peoples will make all these efforts effective.

Here are some of the most important developments that Cultural Survival will follow during these negotiations:

Loss and Damage Fund

Climate change is causing serious damage to the lives and well being of Indigenous Peoples, including the physical loss of lands, waters, territories, resources, and livelihoods. In addition, Indigenous Peoples are suffering irrevocable loss and damages that cannot be quantified by any economic science, including the loss of their identities, languages, cultures, ceremonies, spiritual practices, burial grounds, and other sacred sites. Indigenous Peoples have repeatedly stated that prevention of loss and damage, rather than compensation, should be the first priority. This requires appropriate programs and funding, including direct and transparent access to funding for Indigenous Peoples and their organizations.

The new Loss and Damage Fund was established last year at COP27. While this is one of the most consequential climate decisions since the Paris Agreement, we are yet to see whether this new financial mechanism will actually reach Indigenous communities on the frontlines of climate change impacts. As yet, very little of the money committed to fighting climate change has reached Indigenous Peoples and local communities. According to a 2022 progress report, only seven percent of funds from the $1.7 billion pledge made in Glasgow in 2021 have gone directly to Indigenous Peoples and local communities. As the Transitional Committee on the operationalization of the new funding arrangements and fund established at COP27 to provide recommendations on the new funding arrangements is drafting proposals for the management of this new fund for consideration and adoption at COP28, it is necessary to underscore the importance of increasing direct funding via Indigenous-led or Indigenous-governed mechanisms and organizations to support Indigenous climate solutions and make climate financing efforts effective.

Indigenous Peoples note that any approach to combating and mitigating climate change, including financial flows, must be based on a human rights and Indigenous Peoples' rights-based approach, which did not happen at COP27. This is what Indigenous representatives and organizations will continue to push for at COP28. During the meetings of the Transitional Committee, civil society observers advocated for the allocation of funds to directly benefit the most affected, impoverished, and marginalized groups of the population: including women and Indigenous Peoples. Some parties also noted the need to include a mechanism for communities to have easy, quick, and direct access to funding from the new Loss and Damage Fund. Cultural Survival hopes that the general policy on funding for Indigenous Peoples in the Loss and Damage Fund will reflect the need for direct funding to Indigenous Peoples and their organizations, rather than replicate the ineffective policies of the Green Climate Fund. Established in 2010, the Green Climate Fund was created within the framework of the UNFCCC as an operating entity of the Financial Mechanism to assist developing countries in adaptation and mitigation practices to counter climate change. To date, it has neither accredited nor funded a single Indigenous-led organization.

The Just Transition

The need to move away from fossil fuels, decarbonize the economy, and work towards a Just Transition to a Green Economy is now broadly recognized and understood. One of the main actions at COP28 will be to fast-track the energy transition. At the heart of the energy transition lies a central problem: the massive quantities of minerals like lithium, copper, cobalt, and nickel needed to make that possible. Even more problematic is where and how those minerals are being mined. Recent data reveals a stark reality: globally, 54 percent of the mining projects that involve minerals used in renewable energy technologies are located on or near Indigenous lands and territories. In the United States, a significant percentage of key minerals (97 percent of nickel, 89 percent of copper, 79 percent of lithium, and 68 percent of cobalt) are found within 35 miles of Native American reservations. In Africa, that number is over 75 percent. These projects involve approximately 30 minerals crucial for the production of renewable energy systems.

The dominant narrative as told by mining corporations and electric vehicle manufacturers is that increased mining is essential for the green transition and will lead to a Just Transition for all. However, this narrative fails to address the environmental and human rights concerns associated with traditional mining practices, which have not changed significantly over the last century. Open-pit mines and water-intensive extraction methods continue to pose threats to the environment, climate, and the well being of all people, including Indigenous Peoples. Mining is one of the dirtiest industries in the world, accounting for at least 10 percent of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Extraction on Indigenous territories causes irreparable damage and destroys sacred sites, traditional ways of life, and impacts entire communities’ well being.

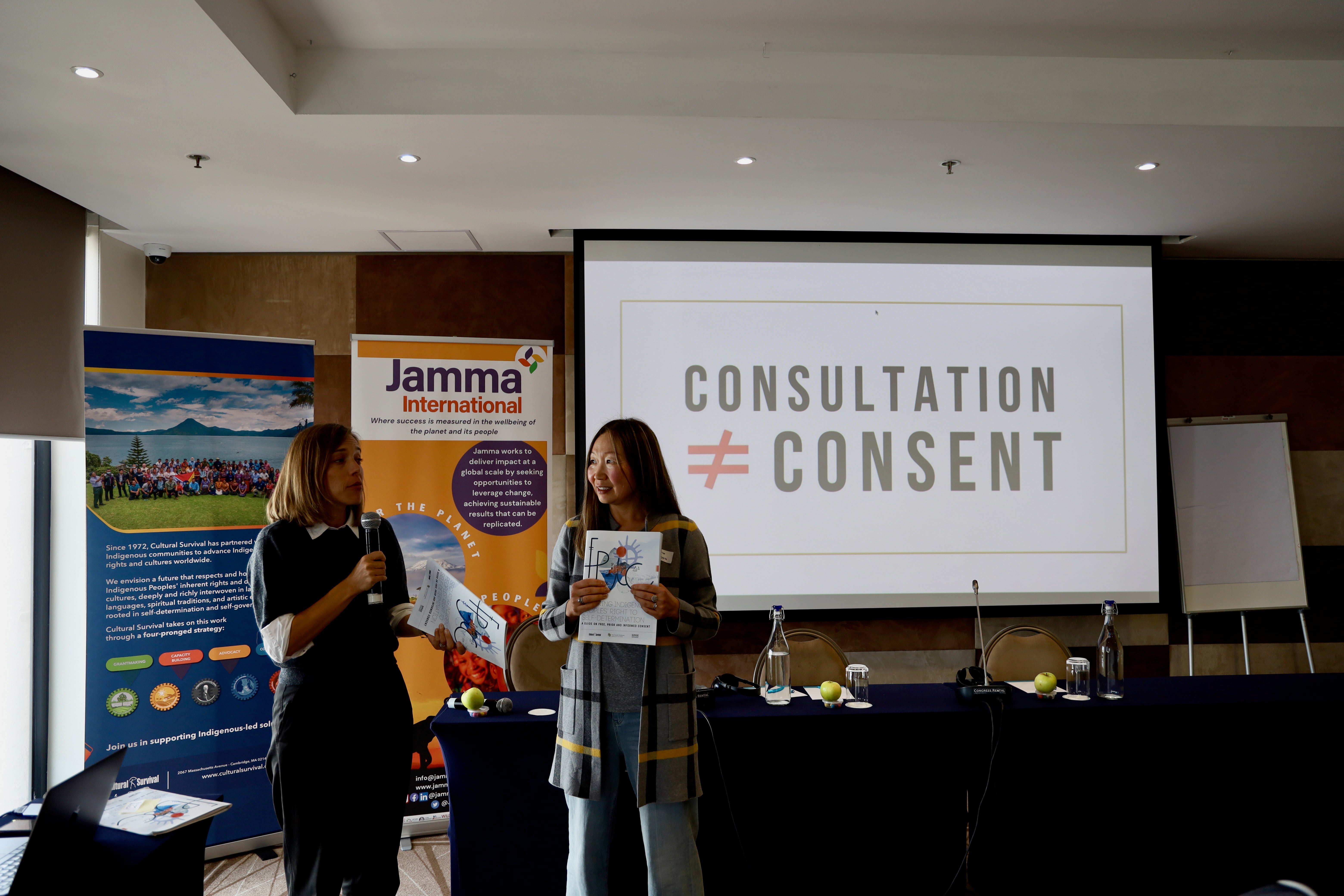

As Indigenous Peoples, we express with one voice that there will never be a Just Transition for all without respecting and upholding the rights of Indigenous Peoples and of communities living near transition mineral projects. We call for the full implementation and operationalization of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), as outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Free, Prior and Informed Consent ensures Indigenous Peoples' participation and consent throughout project development and implementation, providing a crucial safeguard against rights violations. Companies should implement the right to FPIC throughout their supply chains, and policymakers should incorporate mandatory requirements to respect Indigenous Peoples' rights, including FPIC, into policies prioritizing the transition to a green economy and support true solutions that prioritize justice, human rights, self-determination, and Indigenous Peoples' rights throughout the transition process.

Global Stocktake: Why Does It Matter for Indigenous Peoples?

The Global Stocktake is part of the architecture of the Paris Agreement. Article 14 provides that the Conference of the Parties shall periodically take stock, or evaluate, the implementation of the agreement and its goals every five years. The assessment is intended to examine countries’ collective progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, dealing with climate impacts through adaptation, and financing the transformation of systems that contribute to emissions. The first Global Stocktake will take place at COP28 in Dubai. There is no specific target for countries to meet and no enforcement mechanism; the Global Stocktake is a process for countries to assess progress as it relates to the goals of the Paris Agreement in hopes that they will increase their climate ambition.

The recently published synthesis report of the technical dialogue of the first global stocktake outlines that “the world is not on track to meet the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement.” The same report estimates that based on current National Determined Contributions (NDCs), the gap to reducing emissions consistent with limiting warming to the targeted goal of 1.5 °C in 2030 is estimated to be 20.3-23.9 gigatons of CO2: the equivalent of all greenhouse gas emissions of China and the United States combined in 2022.

In the midst of multiple overlapping crises affecting global human rights, the inaugural Global Stocktake is critical for Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous communities, the guardians of the world’s biodiversity, are increasingly under threat. With climate disruptions escalating at an alarming rate and the world’s increasing pursuit of transition minerals exacerbating the issue, research indicates that our efforts to maintain global warming below 1.5°C and achieve all Sustainable Development Goals are significantly lagging. This is a pivotal moment for the world to recalibrate our trajectory.

The outcome of the first-ever Global Stocktake should be clear: countries must pledge to embed a human rights-centric, intersectional approach in all pertinent documents and strategies connected to the Paris Agreement's execution. In other words, the only way to achieve the Paris Agreement is by centering human rights, the rights of nature, and the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Global Stocktake should emphasize the critical role Indigenous Peoples play in shaping robust climate strategies and policy development at all levels, locally, nationally, and internationally. It is distressing to note that Indigenous advocates for climate justice are facing escalating threats of forced displacement, violence, intimidation, and legal challenges. The Global Stocktake must explicitly outline how parties will safeguard the rights of Indigenous Peoples and environmental defenders. It must ensure accessibility to information, encourage public engagement, and honor the rights of Indigenous Peoples to Free, Prior and Informed Consent. It is imperative to Indigenous Peoples, because it provides the tools to map out where and to what degree States have protected our environments and supported our own plans of adaptation and policies for loss and damage.

The Global Stocktake is not just about checking progress. Its purpose is to aid countries in improving their climate actions, promote international cooperation, and assist in creating new climate plans. This is where Indigenous Peoples can and must act to support those goals. For Indigenous Peoples, it is an opportunity to lead the way with solutions that incorporate Traditional Knowledge and science to mitigate climate change. If executed effectively, the Global Stocktake can serve as a basis for guiding climate policies and investment decisions at national and international levels. It can make transformative actions across various systems like energy, biodiversity, food, and transportation. Indigenous Peoples can provide policies and solutions to guide these transformative actions, and therefore must advocate for participation in finance mechanisms.

The Global Stocktake mechanisms are an opportunity to emphasize the value of Indigenous Traditional Knowledge and practices in climate adaptation, encouraging its integration into global climate strategies, and above all, the critical need for prevention and protection. Together, we must seize this opportunity and forge a path towards a sustainable and resilient future for all, honoring the wisdom and stewardship of Indigenous Peoples and safeguarding the intricate balance of our precious Mother Earth.