By Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee)

The communities that comprise Marka Tahua in southwestern Bolivia have always stood as the stewards of one of the most unique and extreme landscapes on earth, the Uyuni Saltflat. The largest salt pan on earth, the Uyuni Saltflat stands as an enormous expanse of salt representing different things to different groups of people—a treasured homeland for Marka Tahua and other Original Peoples, a tourism draw for global visitors, and more recently, the world’s largest known source of lithium. Because of this latter fact, the communities of Marka Tahua stand at the frontlines of this transition mineral extraction and the potential consequences its exploitation could bring to this saltflat.

Marka Tahua represents an overarching jurisdictional grouping of Original, Indigenous communities and peoples who are the stewards of the Uyuni Saltflat’s northern frontier. The leadership and community members often refer to themselves as "Ponchos Blancos, Urkhujs Negros," describing their elaborate and distinctive traditional dress. While the men wear white ponchos and hats that radiate a brilliant white mirroring their saltflat, the women wear a dark colored full dress, reminiscent of the deeper colors of the earth and rocks that ring and dot the saltflat. This clothing serves not only as protection for the human body in this landscape of extremes in temperatures, altitudes, and seasons. More importantly, as my host Jiliri Mallku Pasmaru Efrain Quispe Juarez (Aymara) explains to me, these clothing items are a constant reminder and symbol, “for the people of Marka Tahua that it is their duty to look after, preserve and be stewards of this sacred ancestral territory.”

Ponchos Blancos, Urkhujs Negros standing proudly at the side of Kujiry, or Isla del Pescado, in the middle of the Uyuni Saltflat.

Traveling over the vast expanse of the Uyuni Saltflat together with Marka Tahua traditional leadership.

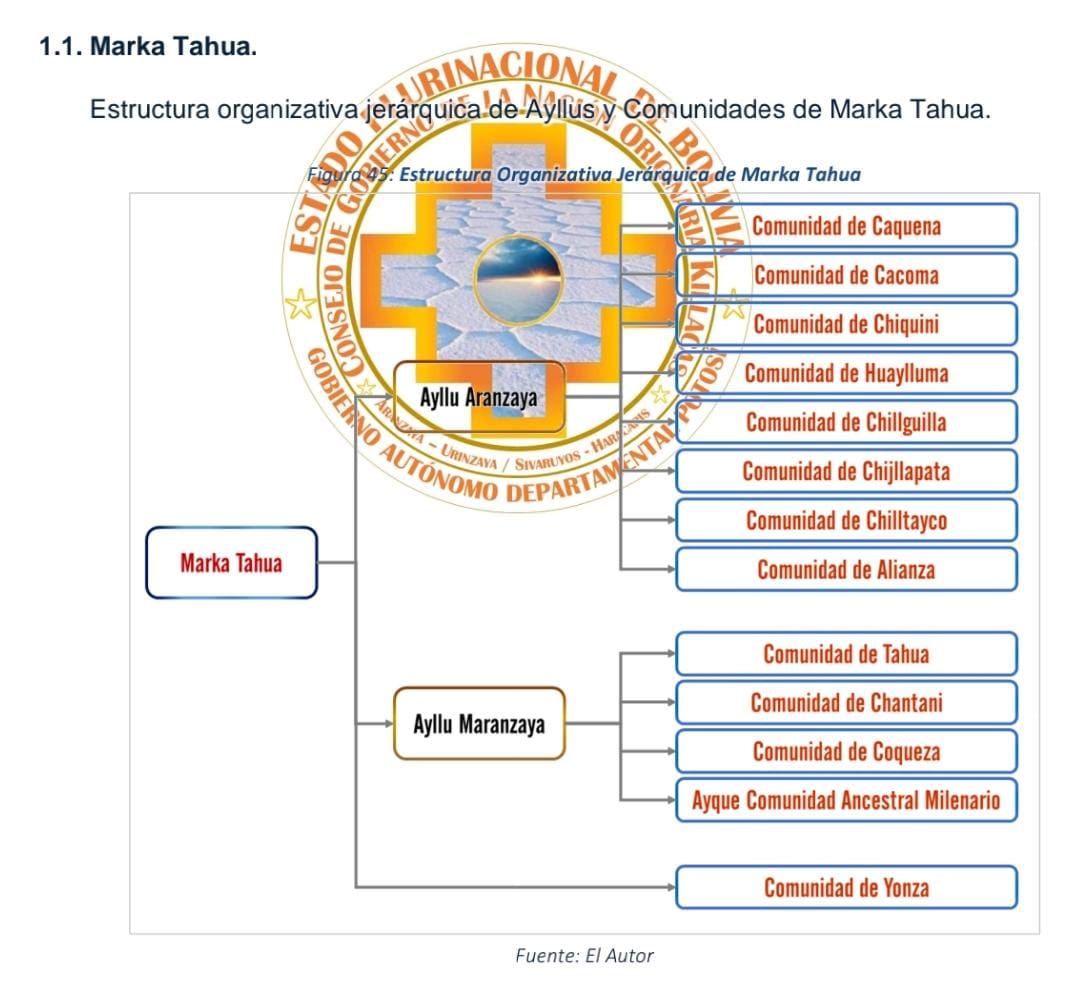

Marka Tahua’s communities ring the base of the sacred Thunupa volcano at the northern edge of the saltflat. As such, Marka Tahua is further subdivided into two distinct Ayllus, or traditional Nation groupings, including Ayllu Aranzaya and Ayllu Maranzaya. In turn, these two Ayllus further subdivide into distinct communities such as Tahua, Chantani, Coqueza, and Huaylluma, among others. Marka Tahua has maintained a deliberate and intricate system of democratic governance and authority over time whereby leaders are chosen based on a balance between the twin traditional concepts of t’aki, or acquired experience, and muyu, or turn-taking. In recent years, Efrain has served as a traditional leader, or Jiliri Mallku Pasmaru. In this capacity, he has been at the forefront of advocating for a resurgence in this traditional governance system and ensuring that its rights and place are recognized within the context of Bolivia’s plurinational state and constitution.

A chart of the organizational authority structure of Marka Tahua jurisdiction that shows the divisions into Ayllus and individual communities.

Over the next two and a half days, every one of the seats in our four-wheel drive vehicle becomes filled as we travel with other leaders of Marka Tahua and their families, known by the Aymara terms as Jilakata (male) and Jikatmama (female). We travel over this landscape as an informal delegation with the aim of hearing directly from the communities about how they perceive the plans for lithium extraction and the impacts it is having on the saltflat. Importantly, we also want to know whether tourism is a preferred alternative and also aim to visit the cultural tourism infrastructure that the Tahua community is building in the center of the saltflat.

Traveling in a full car with Marka Tahua leadership across the jurisdiction to different communities.

Bouncing along the unpaved roads between the communities, our very first stop at each destination are the local churches. Most of these churches stand as the proud heart and gathering point of every community, with unlit, beautiful interior sanctums and humble exteriors and bell towers that have stood the test of time. But just as important as offering our salutations and asking permission at the door of each church is the respect that we must show to what stands on the church’s outside perimeter—the tatamisa and mamamisa. These are the traditional tables that pre-date the introduction of Catholicism in the area, and they serve as gathering points for men and women, respectively, with men at left and women at right. These are the places where visitors are welcomed by local leadership, where men and women share food among one another, and where issues are discussed and decisions are reached. As we approach these special areas, we introduce ourselves and ask permission from the Tata Rey Tatas y a los Uywiris, the spiritual guides that consists of the ancestors and all of the life-bestowing forces that comprise the Pachamama, Mother Earth.

Inside the church’s sanctuary, paying honor and respect to the Tata Rey Tatas y a los Uywiris, spiritual guides, ancestors, and life forces of each community.

“¡Sumará qhipana, que sea buena hora!” we all announce together. “May this moment be good for us all!”, we say with our hands raised up to the azure blue sky above, as we then sprinkle the tatamisa and mamamisa tables with handfuls of inalmama, coca leaves, as well as jhank’o huma, pure alcohol. Then the men gather at their table, and I take a seat with the women at our table. All of us begin to chew on some of the extra coca leaves we share with one another. Efrain rises to introduce me and explain about the role of Cultural Survival. The conversation then quickly turns to the topic of economic pathways, with Efrain often leading the facilitation but men and women both participating in sharing their views and experiences. The consensus is constant. Local community members are concerned about all of the unknowns with lithium extraction, the fact that they are not seeing promises of employment coming to pass, and the worrying changes to their fragile saltflat homeland and its water patterns. Others indicate their bewilderment that it has been almost 15 years since the government first began plans to produce batteries and that industrial production has not developed significantly. Efrain chimes in to tell people, “Part of the problem is that lithium is only one of multiple components—including other metals such as cobalt, graphite, nickel, and copper, among others—required for successful battery production. If Bolivia does not have these other minerals, how are we supposed to make batteries?” When I stand to address the leaders and ask, “What do you think about tourism?”— a unified response from the men and women is, “We support tourism, we would like help and investment to grow tourism. We already have tourism here, but we would like to see more. We are in need of support on this front!”

Some of the male Marka Tahua traditional leaders outside of the local church, congregated around the tatamisa.

Female leadership sitting at the mamamisa, waiting for other women to join.

At another community down the road, the conversation elicits similar answers: there is a strong desire among communities to focus on tourism, as local people see tourism’s potential for keeping young people living in the community and bringing revenue to this area. Locals do not believe that tourism runs the same risks to the environment that extractive processes like lithium mining does. And tourism can also get young people interested in their traditional culture while providing locals the opportunity to share their traditions and stories with visitors. But these same local people are also keenly aware of some of the key challenges they face in this endeavor, including a lack of English language skills, a lack of infrastructure for hosting guests and a lack of training and investment in operating tourism businesses.

The Uyuni Saltflat has been a major tourism draw for Bolivia for a couple of decades now. Within the Marka Tahua network, the Coqueza Community has clearly marked some of its scenic sites with interpretive signage and one family in Chantani Community has operated a small museum for years that attracts a steady stream of visitors. Several Marka Tahua communities are home to unique archaeological sites, most of which do not have extensive signage. Many local archaeological sites are also in need of further archaeological assessments in coordination with community members before being made more accessible to the public.

A popular spot on the saltflat for tourists to take photos and place the flag from their country of origin.

Coqueza community tourism signage that outlines key sites of interest for visitors.

A panorama taken atop a mountainside archaeological site in the Ayllu Aranzaya that overlooks the saltflat.

Another key tourism draw is the Inkahuasi Island, or rocky outcropping that stands in the middle of the saltflat like an island. Covered in cacti and inhabited by native birds and viscacha, or small animals resembling rabbits with long, cat-like tails, Inkahuasi is a key stopping point for visitors to the saltflat and charges admission. But according to Efrain, the administration and revenue distribution has ultimately not been of benefit to communities throughout Marka Tahua, and unfortunately, Inkahuasi is not the only example of this. This is why from Efrain’s perspective, “it is so important to make sure that tourism is benefitting our communities and that tourism is directed through the authority of our Marka Tahua traditional governance. It is a matter of aligning tourism with our traditional values, governance and our unique Andean-Amazonian cosmovision that is Indigenous to this place.”

Inkahuasi Island covered in cacti.

A map on Inkahuasi Island showing the Inkahuasi in the saltflat center, as well as Marka Tahua communities on the northern border.

Our discussion of the challenges and aspirations is put to the side as some of the local women come forward with large pots of food and beverage. Decorated clay vessels are filled to the brim with local specialties, including stuffed potatoes, grilled llama meat, homemade cheese and small, rehydrated potatoes. But it is the quinoa real, or royal quinoa that stands out as the star item. Locals tell me, “For our Aymara brothers to the north, the potato is king. But here, our lives revolve around quinoa.” This grain is fluffy and light when cooked whole and I am served a heaping bowl of quinoa with grilled llama meat on top. But the feasting does not stop there, as elder women from the community come to fill my bowl with other local specialties of this sacred grain— quinoa as a drink mixed with water and sugar, quinoa flour-based buñuelos or frybread, and ‘chicle de quinoa’ or quinoa pounded into chewy balls.

Local specialties made of royal quinoa including frybread and quinoa balls.

Grilled llama meat served atop a bed of royal quinoa.

Marka Tahua leadership delegation being served a hearty lunch, with Efrain seated (seated) and author (second from right) standing with women.

Marka Tahua leadership delegation being served a hearty lunch, with Efrain seated (seated) and author (second from right) standing with women.

While the Incan civilization was known to have called quinoa the “mother grain,” the United Nations declared 2013 the Year of Quinoa and bestowed upon this grain the status of world superfood. Quinoa comes in more than 3,000 different varieties and has become particularly prized around the world for its high nutritional density and gluten-free characteristics. But long before globalization took quinoa by storm as a popular health food, it has always been viewed as a sacred source of sustenance and nutrition in these communities. It is, after all, one of the only plants that can be successfully cultivated at this high altitude of 3,600 feet above sea level and has not required large quantities of water for irrigation. Around the saltflat, the relationship to quinoa is particularly special as this area of Bolivia is the only place in the world where ‘royal quinoa’ grows. Royal Quinoa is a variety that grows taller and is even more nutrient dense compared with other varieties, whether measured by fiber, protein, vitamins, phytoestrogens or amino acids. For the local communities, these exceptional qualities of royal quinoa are indisputably connected to the mineral-rich landscape that they inhabit between the saltflat’s underground brine and the volcano of Thunupa. Royal quinoa’s status as the true king of superfoods thus comes as no surprise whatsoever.

Most of the communities that comprise Marka Tahua are actually in the process of quinoa harvesting as we visit, using traditional methods to separate and collect this precious grain. Locals explain that the process generally involves threshing early in the morning to avoid humidity. Trucks will drive over the quinoa which helps to separate the grain from the stems before it is later sifted. One of the most important steps in harvesting quinoa is removing the saponin, a bitter-tasting chemical on the grain’s outer shell that protects the inner contents from disease and pests. Royal quinoa has more saponin than other plants and this characteristic is what gives the plant its hardiness to grow in such an extreme environment such as this. Yet for all of royal quinoa’s resilience, it has been shown to be susceptible to climate shifts that the area is increasingly seeing, as recent years have brought inconsistent weather patterns of both drought and deluge.

The distinctive colors of the royal quinoa plant.

In this season after the rain, community members across the saltflat harvest quinoa.

A community member of Caquena stands proudly with quinoa he has grown, with Thunupa volcano in the background.

But as our vehicle continues to make a full loop through Marka Tahua and stop at its different communities, it is clear that this area’s natural gifts do not end at royal quinoa. Female leaders Tia Martha Huayllani Paulo and Tia Irma Mamani Huarachi hop out of the car at various points and show me these incredible wonders. “This plant here is baila baila, when we prepare it with hot water as a tea it helps to alleviate stomach pains,” says Tia Martha. At the side of a shallow stream, Tia Irma pulls up the fresh sprouts of a green plant growing on the sides of the stream. She gives this handful of sprouts a quick rinse in the cool, flowing fresh water before handing it to me and inviting me to try it. Its tiny, fresh leaves and slight peppery bite take me back instantly to my own homelands in Oklahoma where we Cherokees relish a similar form of watercress that grows along our creeks and streambeds in the springtime. Perhaps one of the most moving stops is to a natural ‘ojo de agua’ or spring that bubbles not with salty, brine-rich water as in the adjacent saltflat, but instead bubbles with gaseous mineral water. We each take turns dipping in our mugs and enjoying this gift of sparkling water as nearby llamas move about in small groups, watching on inquisitively to see what we are doing.

Savoring the delicate green leaves growing along the side of a stream.

Enjoying conversation and natural gaseous mineral water at the spring on the border of the saltflat.

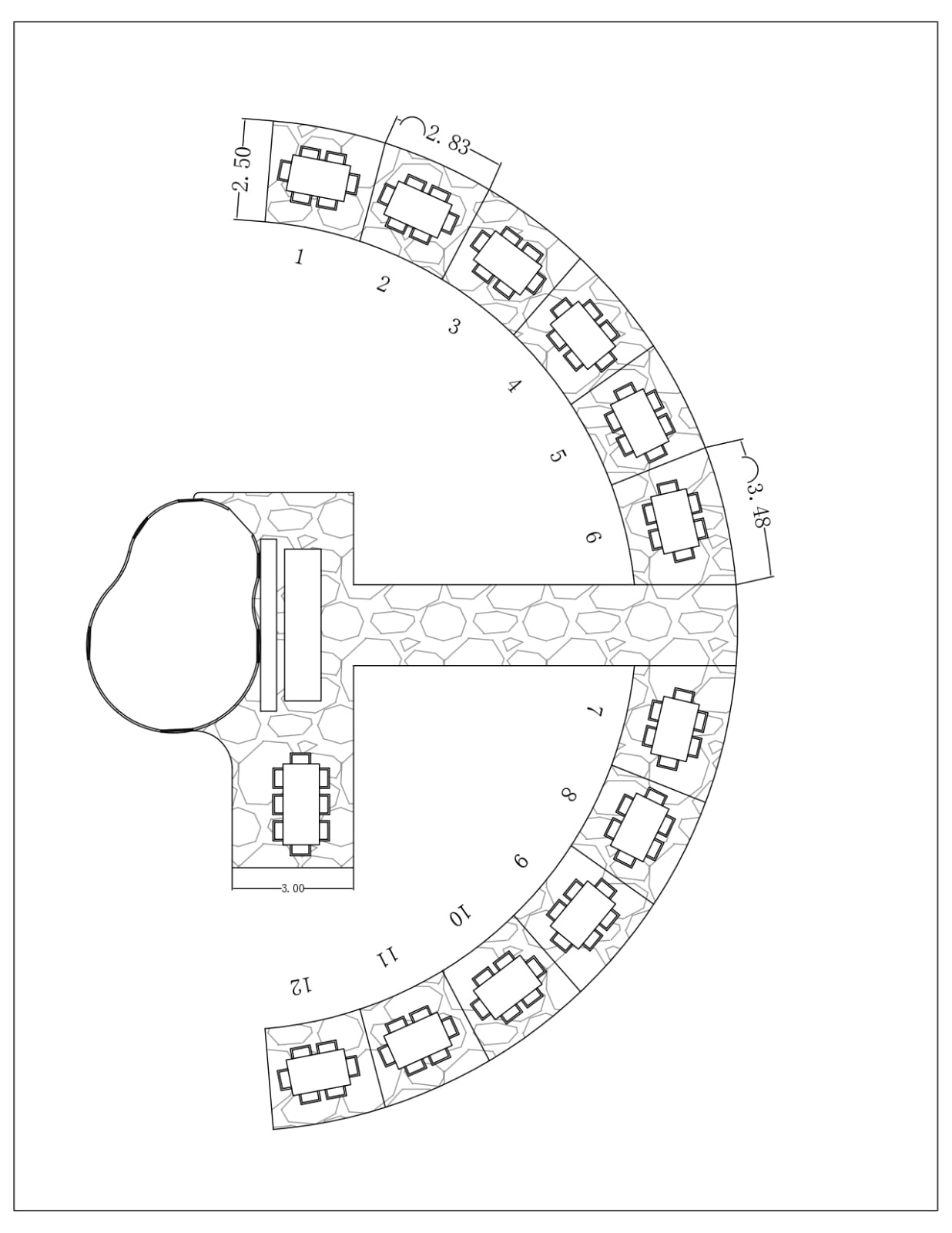

Having visited with the different communities and natural wonders comprising Marka Tahua, as well as having heard the consistent voices advocating for community-led cultural tourism, the final stop of our caravan is to Isla Kujiry. Kujiry, also known as Isla del Pescado, or Fish Island, is another cactus-studded island in the middle of the saltflat. Our visit here feels like a culmination of all the experiences and perspectives shared on the Uyuni Saltflat. It is here on the eastern shore of the island that the Tahua community, supported by Cultural Survival’s KOEF funding, is constructing a building to be able to promote and host cultural tourism controlled by the community. Yet the floorplan that Efrain shows me and the stone wall constructed are not for just any building. The construction underway is for a cultural tourism hub that reflects and is embedded within the cultural protocols of Marka Tahua, namely the importance of visitors to introduce themselves, seek permission of the local authorities and then learn from their hosts. This emerging infrastructure is designed as a set of tatamisas and mamamisas that represent each of the 13 communities across Tahua, all aligned in a semi-circle that faces east, towards the direction of the rising sun.

Marka Tahua traditional leaders standing on the saltflat looking towards Kujiry.

Construction floorplan of Tahua’s cultural tourism infrastructure on Kujiry.

Efrain and the other traditional leaders explain that the objective of this tourism development is for visitors coming onto Kujiry Island to have a cultural experience, in addition to appreciating this unique saltflat landscape. The leaders say, “We want for visitors to come here and learn about our strong culture in Marka Tahua, that we are the original stewards of this Uyuni Saltflat. We want tourists to learn about what it means to wear Ponchos Blancos and Urkhujs Negros, and what it means to follow our original economic model. Our original economic model is based in a system of distribution to communities, it is not based in exploitation of the land and water.”

While it is Tahua that is at the forefront of this project, nearly all of the other communities have also shown the willingness to participate in this collective tourism initiative. According to Efrain, each of the communities will use their own resources to construct their own tatamisa and mamamisa within the site. Efrain tells me that the leadership also envisions this site as one where tourists can experience local music and dances that are typically associated with the time of Carnaval.

Leadership delegation standing in front of the construction progress in mid-April 2024.

As our group sits down to observe the progress and discuss plans for the future, Efrain reflects that, “When we are talking about economic activities, everything comes with some level of pollution, everything in life has an impact upon the greater living system. However, the level of pollution and harm that comes from tourism is less compared with the extraction of natural resources such as lithium or copper. Much less. Overall, tourism brings with it both direct and indirect income sources. Tourism is a tool that our communities can use to create the futures that we want as the original peoples and stewards of this place.”

Tourism infrastructure progress in mid-July 2024. Photo credit: Efrain Quispe Juarez.

Journeying across the Uyuni Saltflat in the direction of the late afternoon sun.

Taking in the blindingly white vistas of the Uyuni Saltflat that surrounds us on this island, it is hard to imagine how visitors cannot be transformed by a visit to this sacred landscape. It is also nearly impossible to imagine how the experience of visitors would not be enhanced by connecting to the Original Peoples and Stewards of this unique saltflat. I, for one, have been humbled and touched at each turn and conversation along the road. But even more important than transforming visitors is the potential that increased investment in tourism holds for Marka Tahua, the traditional stewards. The near-unanimous perspective among Marka Tahua communities that sees tourism not just as an economic tool and a compromise in engaging with industry but as a potential force for strengthening their own connections to traditional culture, governance, and land is powerful. These voices need to be listened to, heard, and respected.

Tourists visiting the Ayque Community in 2016. Photo credit: Efrain Quispe Juarez.