By Kisha James (Aquinnah Wampanoag and Oglala Lakota) and Mahtowin Munro (Oglala Lakota)

What are the foundational myths of the United States? Who created them and who is erased and harmed? For the past 51 years, United American Indians of New England (UAINE) and supporters have gathered on so-called Thanksgiving Day in Plymouth, MA, to ask these questions, confront settler mythologies, and commemorate a National Day of Mourning for Indigenous Peoples devastated by settler colonialism and imperialism.

The National Day of Mourning protest was founded by Wamsutta Frank James, an Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribal member, and other Indigenous men and women in the region. In 1970, Wamsutta had been invited by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to give a speech at a banquet commemorating the 350th anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims. The organizers of the banquet imagined that Wamsutta would give an appreciative and complimentary speech, singing the praises of the American settler colonial project and thanking the Pilgrims for bringing “civilization” to the Wampanoag. However, the speech that Wamsutta wrote, which was based on historical fact instead of the hollow fiction portrayed in the Thanksgiving myth, was a far cry from complimentary.

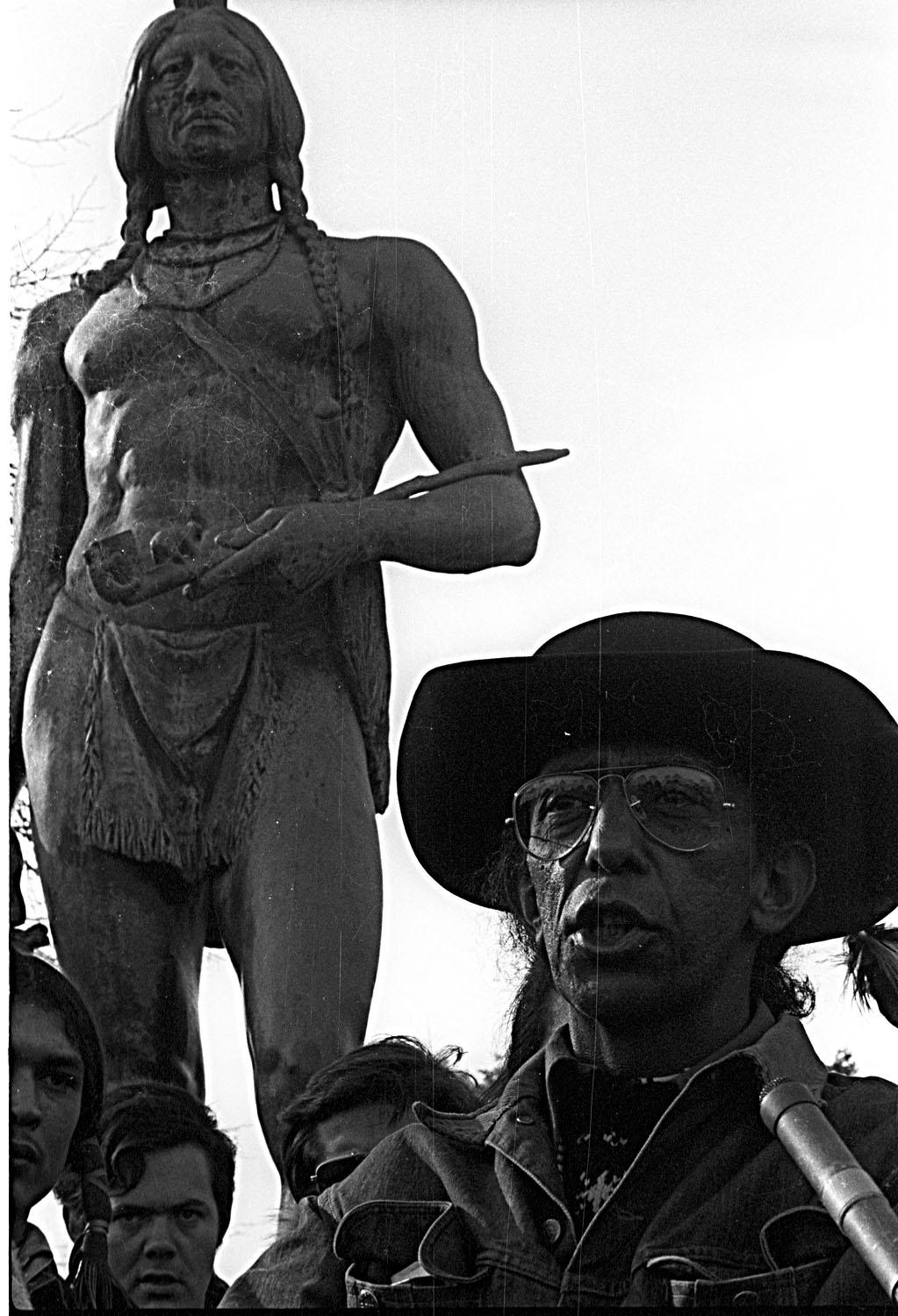

Wamsutta Frank James (Aquinnah Wampanoag)

In his speech, Wamsutta not only named atrocities committed by the Pilgrims, but also reflected upon the fate of the Wampanoag at the hands of settlers. He described how the English even before 1620 brought diseases that caused a “Great Dying,” and how they took Wampanoag people captive, selling them as slaves in Europe for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims themselves robbed Wampanoag graves immediately upon their arrival. These settlers also led Wampanoag people to believe that, if they did not behave as the Pilgrims thought fit, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again. Moreover, although there may have been a meal provided largely by the Wampanoag in 1621, it was not a ‘thanksgiving.’ Rather, the first official “thanksgiving” was declared by the Puritans (not the Pilgrims) in 1637 to celebrate the massacre of hundreds of Pequot men, women and children on the banks of the Mystic River in CT. Within fifty-odd years of the arrival of the Pilgrims and other Europeans, the Wampanoag along with many other Tribes had been devastated due to warfare, disease and dispossessed of most of their ancestral lands. Those who resisted were killed and their families enslaved.

The suppressed speech also contained a powerful message of Native American pride. “Our spirit refuses to die,” wrote Wamsutta. “Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting… We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we'll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us.”

When state officials saw an advance copy of Wamsutta’s speech in 1970, they refused to allow him to deliver it, saying that the speech was too “inflammatory.” The speech was clearly inspired by the fledgling “Red Power Movement,” which demanded equal rights and self-determination for Native Americans. This without a doubt frightened the state officials, whose minds were likely drawn to think of the 1969 Occupation of Alcatraz, a 19-month long protest where Indigenous Peoples took over the abandoned federal penitentiary on Alcatraz Island in California. The Occupation of Alcatraz had been one of the first intertribal protests to garner national attention, and it had struck fear into the hearts of politicians and other settlers because it was becoming clear that Native Americans, like Black and other oppressed Peoples, were saying “no more.”

Clinging to the Thanksgiving mythology, the state officials told Wamsutta that they would write a more “appropriate” speech for the banquet, but he refused to have words put into his mouth. His suppressed speech was printed in newspapers across the country, and Wamsutta decided that something had to be done to ensure that the truth about the Pilgrims was heard loudly in Plymouth itself. He and other Native activists from UAINE, the Boston Indian Council (now North American Indian Center of Boston), and elsewhere began to plan a protest. The flyer for this protest, which was circulated among Native people nationwide, read, “What do we have to be thankful for? The United American Indians of New England have declared Thanksgiving Day to be a National Day of Mourning for Native Americans.”

Word of the day spread, and members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) such as Russell Means and Dennis Banks as well as other Native people from other parts of the country, traveled to Plymouth, MA, for the very first National Day of Mourning. On November 27, 1970, a crowd of around 200 Native Americans and supporters gathered on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, MA. Native American leaders made speeches about the deplorable conditions Native Americans faced, the genocidal actions of the United States government, and the devastation caused by the Pilgrims. The group then made their way down to the waterfront where they buried Plymouth Rock in sand and painted it red. A small group of protesters made their way over to the Mayflower II, a replica of the original Mayflower, and boarded the ship. They climbed the rigging and tore down the flag of Saint George, the patron saint of England. They also tossed a wax statue of the captain of the Mayflower, Christopher Jones, overboard along with the flag of Saint George. The protesters then made their way to a recreation of the first Thanksgiving dinner, where they flipped over tables, saying that they “would not eat the white man’s food.”

Indigenous Peoples and allies have continued to gather on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth to observe a National Day of Mourning every year since then. At the 1972 National Day of Mourning, a young woman, Judy Mendes, was attacked by the police for wearing an upside-down American flag draped over her shoulders. At the 1974 National Day of Mourning, Wamsutta and others liberated the bones of a 16-year-old Wampanoag girl from the Pilgrim Hall Museum. In 1997, National Day of Mourning organizers and protesters were attacked and brutalized by combined forces of the Plymouth police, county sheriffs, and state police. Twenty-five protesters were arrested, and the resulting court case and settlement led to the installation of two historical plaques in Plymouth with an Indigenous-written historical account, the charges being dropped against all 25 protesters, and acknowledgment of the right to march without a permit each National Day of Mourning.

Indigenous Peoples and allies from the Four Directions will gather on Cole’s Hill on November 25, 2021, and will continue to do so into the future. As Moonanum James, son of Wamsutta Frank James and the late co-leader of UAINE, said to the crowd at the 2019 National Day of Mourning, “We will continue to gather on this hill until corporations and the U.S. military stop polluting the Earth. Until we dismantle the brutal apparatus of mass incarceration. We will not stop until the oppression of our Two-Spirit siblings is a thing of the past. When the homeless have homes. When children are no longer taken from their parents and locked in cages. When the Palestinians reclaim the homeland and the autonomy Israel has denied them for the past 70 years. When no person goes hungry or is left to die because they have little or no access to quality health care. When insulin is free. When union-busting is a thing of the past. Until then, the struggle will continue.”

National Day of Mourning does not only focus on the past. Speakers talk about many contemporary issues, as well. Issues that we expect will be raised this year will include the ongoing defense of land and water against pipelines such as Line 3 and mining projects, missing & murdered Indigenous women (#MMIWG2S), the intergenerational trauma caused by the government-run residential schools, the need to locate and return the remains of the thousands of children who died at those schools, the attacks on Indigenous children today through foster care and efforts to overturn the Indian Child Welfare Act, Indigenous movements for land and sovereignty from Chile to British Columbia, and the continued US detention and denial of human rights to our migrant relatives at the southern borders. We also express solidarity with other movements, such as the Movement for Black Lives, because we believe our liberation is intertwined with the liberation of others. Prerecorded content will include messages about the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) struggle, Mapuche and Palestinian resistance, Northeast Megadam Resistance, and The Red Nation.

In all of its work, whether organizing National Day of Mourning or leading Indigenous Peoples Day efforts, UAINE seeks to unite Indigenous Peoples, center Indigenous Peoples’ voices, learn from each other, and educate non-Native people as well. Now more than ever, non-Native people need to learn the truth about the impact of colonialism and listen to what Indigenous Peoples have to say about many issues, especially frontline Indigenous perspectives and wisdom on how to properly and immediately address the climate crisis.

Watch and listen to the November 24, 2022 livestream here at 12:00pm ET:

Watch the recording of the November 25, 2021 event here:

--- Kisha James is an enrolled member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) and Oglala Lakota. She is a youth organizer and archivist for United American Indians of New England (UAINE) and a youth organizer for the statewide MA Indigenous Peoples Day campaign. Kisha is the granddaughter of Wamsutta Frank James. Kisha now co-leads the organizing efforts for the National Day of Mourning. She regularly gives speeches to public groups, private organizations, and classrooms across New England and the U.S. as a whole around rethinking the Thanksgiving myth.

Mahtowin Munro (Oglala Lakota) is the co-leader of United American Indians of New England (UAINE). Mahtowin speaks to many students and community organizations, has led and advised on multiple Indigenous Peoples Day campaigns through IndigenousPeoplesDayMA.org, and works to pass Indigenous-centered legislation in Massachusetts through MAIndigenousAgenda.org.

All images courtesy of United American Indians of New England.