The Mashantucket Pequot Museum's recent exhibition, "Native New England Now," which ran through January 4, represented tribal communities from all six states in New England, displaying Native art from twenty-seven different artists in a serene and spacious setting. The exhibit was made possible by a partnership between the museum and the New England Foundation for the Arts.

Four of the featured artists also participated in a panel discussion on the importance of art relative to Native American culture: Jeanne Kent (Nulhegan Band, Coosuk Abenaki of Vermont), Elizabeth James-Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag), Robert Peters (Mashpee Wampanoag), and Jennifer Kreisberg (Tuscarora of North Carolina). The notion of spirituality within art is a common theme for Native artists as well as contemporary artists, and the panelists expressed their belief that art is not separate from culture: they are one in the same. Their creations reflect their lifestyles, beliefs, and history, and are also a reflection of the lands off which Native people live. Some of the creations were made primarily from materials harvested from the earth, such as gourds or wampum beads. Perry commented, “As artists we enjoy work that brings happiness and peace. The world today is scary with climate change and the loss of Native communities.”

Art is necessary for spiritual replenishment, and the sense of spirituality proliferated throughout the exhibit. Trudie Lamb Richmond, a NEFA board member and the former director of public programs at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, said she could feel the energy of the art and peace in the exhibit. Peters elaborated: “What NEFA has done is given artists an opportunity to do their work. People choose to do work that is spiritual or meaningful.” In addition to cultural expression, the artists also described the need for their art to be a means to express themselves personally. Kent explained that she “had to create to breathe,” adding, “if I don’t create, I die.” She further described how coming to Native art has been spiritually satisfying, and recalls the non-Native art she did previously as being “like eating junk food, not fulfilling.” Kent's art helps to bind together her Native Abenaki community.

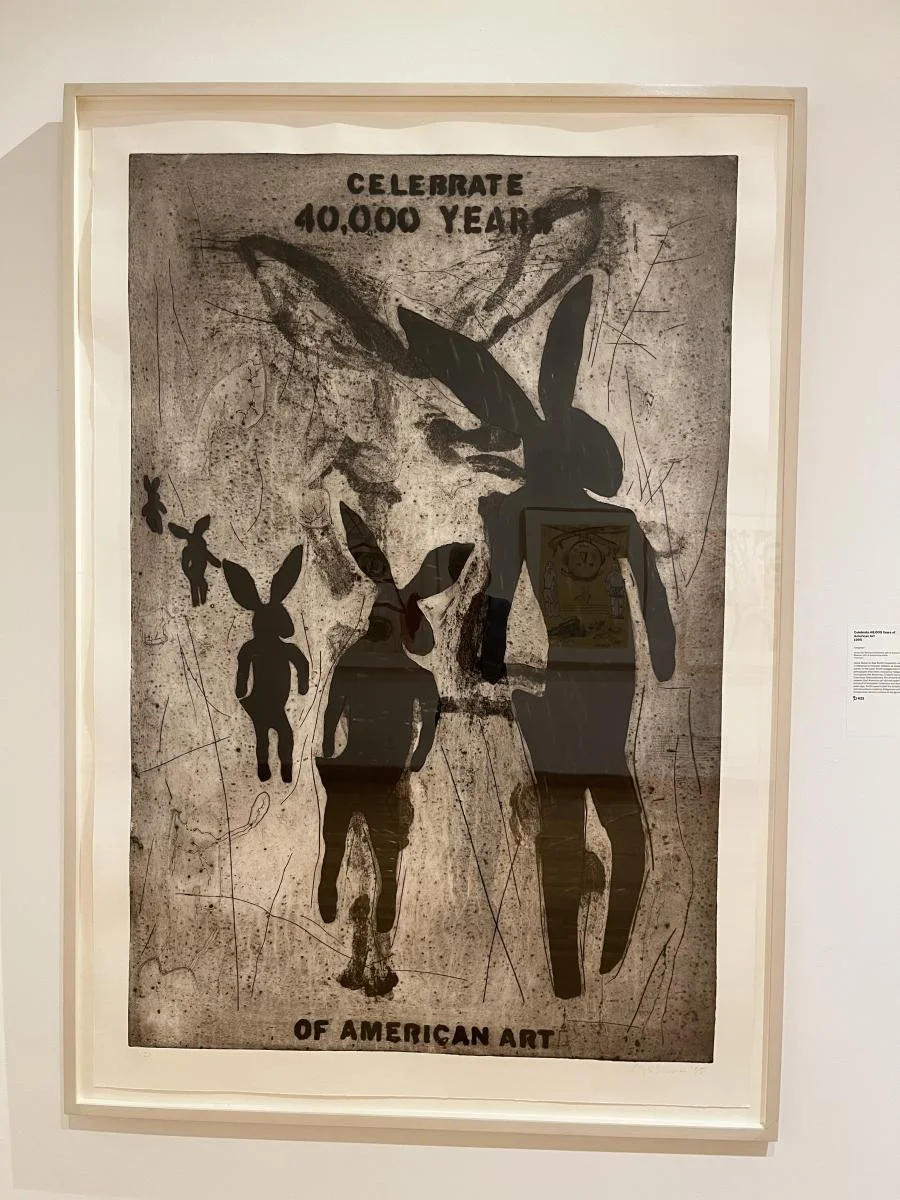

For Peters, art is also a way to tell the stories of his childhood on a reservation. He draws on memories, which are often faded, but says that “when they come back, it’s like, ‘whoa.’” His work primarily draws on events from everyday life that he remembers from the 1970s. One of his paintings is of people and fire trucks at the scene of a forest fire. He remembers this fire persisting for six months, and that anyone in the community who hopped on the back of a fire truck could be a fireman. By painting the fire on the very edge of the canvas, he highlights the community’s involvement in the center of the painting rather than the fire’s destruction. Another of his paintings shows a drum circle and people surrounding a fire pit. The people are all wearing modern clothing, illustrating that Native culture is both current and evolving. He described the world of his reservation as one in transition, having to file petitions for land that had been public for 100 years, and that they were losing control of their town offices and selectmen. Indeed, his work displays this transitioning world. Peters underscored the importance of creating the visual record of his childhood: “If I didn’t take the time to paint our way of life at that particular time, there is a strong possibility no one else would.”

Just as art is a tool for preserving memory, it also has the power to heal. For Kreisberg, it has helped to heal her frustrations and anger at the injustices and inequality in the world. She described art as “making medicine,” and said that when she performs, she lets “spirit take control [to] get out what’s inside.” In many cases, what’s inside can be oppression or a disconnect from culture and or resources. As Peters said, Native peoples are often systematically disadvantaged because of shortages of wealth and resources. Accordingly, “Our way of thinking has changed. We went from looking at generations in the future to looking only a week ahead. This is a disadvantage for caring for the future of our world." Perry added her view that keeping Native communities together is challenging but worthwhile, pointing to the difficulty of finding jobs and the fact that Native people have to leave their communities to receive a university education. “We all have to work harder to create communal spaces for the arts in our homelands,” she said.

But, she also sees a future for Native communities. Describing Native Algonquian culture as cyclical, Perry said at times it has slept. “I had the good fortune to be mentored by many well-respected Wampanoag artists and teachers who developed the early programs and exhibits at museums like the Boston Children's Museum and Plimoth Plantation, some of whom have since passed away.” She has been able to recapture the technology of Native crafts and seeks to express common cultural values through visual and spiritual arts, “sharing our past as well as our future.” On a similar note, Kreisberg said that people have to “keep finding ways to make community” and “make good use of our time” on Earth. “We have to,” she asserted, and by doing so “we are making a better place in the world.” Having a child brought her to the conclusion that such an outlook is necessary, because she can’t bear to think that she has brought a child into a cruel and dark world.

Peters also spoke about the satisfaction of “bringing light” to his culture, that his art and others’ “shows that we still have a future,” and that while “the world isn’t always kind, sometimes you need to fight.” Indeed, these artists are fighting to preserve and recreate their culture, and organizations like NEFA are helping them do just that. As Kreisberg concluded, Native artists must support each other, and supporting an organization like NEFA keeps their culture thriving.

—Amy Ferguson and Sara Schenkel are former Cultural Survival interns.