Last fall, Indigenous Peoples from around the world came to stand with Standing Rock on the banks of the Cannonball River in North Dakota to protect water through the power of prayer, occupation, and protest. Standing Rock has become a much bigger symbol for the ongoing disregard of Indigenous rights to traditional territories and ways of life.

Tara Houska (Couchiching First Nation), national campaign director for Honor the Earth, described what happened at Standing Rock at the October 2016 Indigenous Forum, hosted by Bioneers: “The stories are the same no matter where you go around the world with Indigenous people. It’s always this extractive project contaminated our drinking water; this industry is preventing us from exercising our rights to hunt and fish; our traditional foods are dying; our children are sick; our elders are sick; we have cancer clusters. Standing Rock has become for Indigenous people this moment where they’re all standing together because they all know what happens when something like this is allowed to happen to them and to their communities.”

Tears of joy after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers pulled the project permit in December were replaced with tears of anguish in January when President Trump issued an executive action to steamroll ahead with the pipeline as part of the administration’s aggressive pursuit of a fossil fuel-based national economy. As of February 2017, water protectors are still fighting for the health and safety of all Americans, including those yet to be born, who will suffer ill-effects of this pipeline.

Across North America, pipelines have resulted in massive disruptions to ecosystems. Contamination from extraction practices have resulted in increased health problems, including birth defects and cancers among people and animals. Indigenous women have been beaten, raped, and killed by transient construction workers and black economy criminals that surround the extraction industry. CEOs give orders to deliberately demolish burial grounds and sacred sites, and those who resist are met with rubber bullets, tear gas, attack dogs, bright lights, and cold waterboarding. In any other context these flagrant displays of human rights violations would be tried as domestic terrorism.

It is easy to blame construction workers, corporate CEOs, public servants, and our elected officials for greenlighting pipelines. But focusing on individuals obfuscates the bigger issue: that North American political and legal systems are organized to benefit settler colonial interests. As Eriel Deranger (Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation), founder of Indigenous Climate Action, explained in a recent keynote speech, “Indigenous communities have faced centuries of systemic oppression that has robbed us our ability to easily enter local, national, and international forums where policies and decisions are being made that ultimately affect our rights and our cultural survival.” Tribal sovereignty is always under threat. Treaties continue to be violated. The obligation to consult with Tribes to obtain Free, Prior and Informed Consent for extractive projects is easily circumvented by steak dinners and sellouts. Without an understanding of colonization driven by the insatiable consumption of natural resources, the public can’t make critical connections between the environmental and human rights abuses on Indigenous ancestral territories and their own lives.

Until Standing Rock captured the international spotlight, Indigenous environmental battles represented a largely underground movement. In recent years, Indigenous communities have been organizing and resisting environmental threats more effectively than ever before, amassing an arsenal of indirect and direct action strategies that came together at Standing Rock. These include place-based prayer, blockades, and occupation of lands under threat combined with outside legal action. As Deranger said in her speech, “Because of our unique relationship with our lands, Indigenous people have been utilizing a platform created by our ancestors, the foundations of our culture, to safeguard our river systems, our food systems, our culture, our identity, and our land base.” These cultural platforms—the traditions, knowledge, and world-views that guide our battles as Indigenous Peoples—are intimately tied to the land and water.

Throughout 500 years of colonization, North American Indigenous Peoples have asserted their rights over ancestral territories through occupation of the threatened cultural landscape. Seven years before the Oceti Sakowin camp was established on the banks of the Cannonball River, the Unist’ot’en Clan of the Wetsu’wet’en Nation founded a homestead on their unceded territories to prevent several proposed pipelines. Inspired by what has happened at Standing Rock, Indigenous Peoples have now organized to fight against the Trans-Pecos Pipeline in Texas and the Trans Mountain pipeline in Canada.

Dallas Goldtooth (Dakota/Diné) of the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) describes the broader mobilization against extractive development under the Indigenous Rising campaign: “It’s a project of IEN, but it’s also just a general concept that’s out there that resonates across the diaspora of Indigenous Peoples . . . this is a critical moment we find ourselves on this planet, not just in the sense for addressing climate change, but also a sense for social justice, a sense of just overall justice for all species. Indigenous Peoples tend to be, and rightfully are, on the frontline of those fights and those struggles. And that’s encapsulated by this idea of us rising together.”

Indigenous occupation movements have successfully collaborated with non-Indigenous environmental groups to stop several proposed pipelines across North America. But building broad public support around this issue as the world witnessed at Standing Rock has proven challenging. Penobscot environmental scholar and chair of Native American Programs at the University of Maine, Darren Ranco, explains, “Because our cultures are so always tied to specific places, the names of our places, and the sacred elements of our places, the challenge is always to articulate our view not as a specific claim of a small group of people, but as a broad claim about the rights of all of us.” Similarly, Deranger pointed out that, “it’s imperative that we work together to find ways to address the roots of oppression and not get lost in surface issues like simply protecting a piece of land, as was commonly done by early inceptions of the environmental movement. It’s become imperative that we work together to address colonialism, racism, sexism, and the continued marginalization of those that have been deemed less worthy.”

According to Ranco, “These ways of articulating across the intersectional quality of the movement is why people are paying attention to [Standing Rock] in this moment.” To this end, water protectors have successfully communicated the issues at stake in two ways. Through the “water is life” campaign, they helped the public make the connection between a pipeline threatening water in their little corner of the world in North Dakota, the potential impacts for millions downriver of a spill, and the need for local vigilance over environmental threats to water in other parts of the world. And through social and other media outlets, they told a story of Standing Rock that is not just about climate justice, but also about the integrity of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution through freedom of the press.

By being able to see events unfold at Standing Rock via social media, people who care about a multitude of issues were able to intimately connect to the water protectors on the front lines. “It wasn’t until people saw us on Facebook live and Instagram and Twitter and Native social media—people getting arrested just for standing there—that people started noticing,” said Kandi Mossett (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara), Native Energy & Climate Campaign organizer with Indigenous Environmental Network, at the 2016 Bioneers Indigenous Forum.

Standing Rock has endured in the public consciousness as many other “news items” have come and gone. People from all walks of life have come to care deeply for what Standing Rock means to them, from protecting sacred water to women’s rights, Native American sovereignty, environmental racism, climate change, free speech and more. Charles Menzies, professor of anthropology at the University of British Columbia and member of the Gitxaala Nation, suggests that to continue to show their solidarity with Standing Rock, “Someone can start from the most radical action of going and offering support in the camps. There’s also the whole idea of trying to learn and to really understand the issues. That in itself is an act of solidarity. So instead of building upon misconceptions that people already carry, they can actually build their solidarity with knowledge. Paying attention to the local struggles in one’s own community is really important. People can build solidarity with larger actions further afield by actually starting at home and build from connective points to larger issues. By having conversations about what’s happening in your local communities, people can begin to engage at the wider level. And if people have cash, they can support legal defense funds. Oftentimes, these political actions require legal defense. These things always cost money.”

—Alexis Celeste Bunten, Ph.D., is an Alaska Native applied anthropologist who manages the Bioneers Indigeneity Program. She has written about the aftermath of Indigenous land claims and Indigenous economic development through cultural tourism.

Photo: Tara Houska, Kandi Mossett, and Dallas Goldtooth present an update on the situation at Standing Rock at the October 2016 Bioneers Conference. Photo by Jan Mangan.

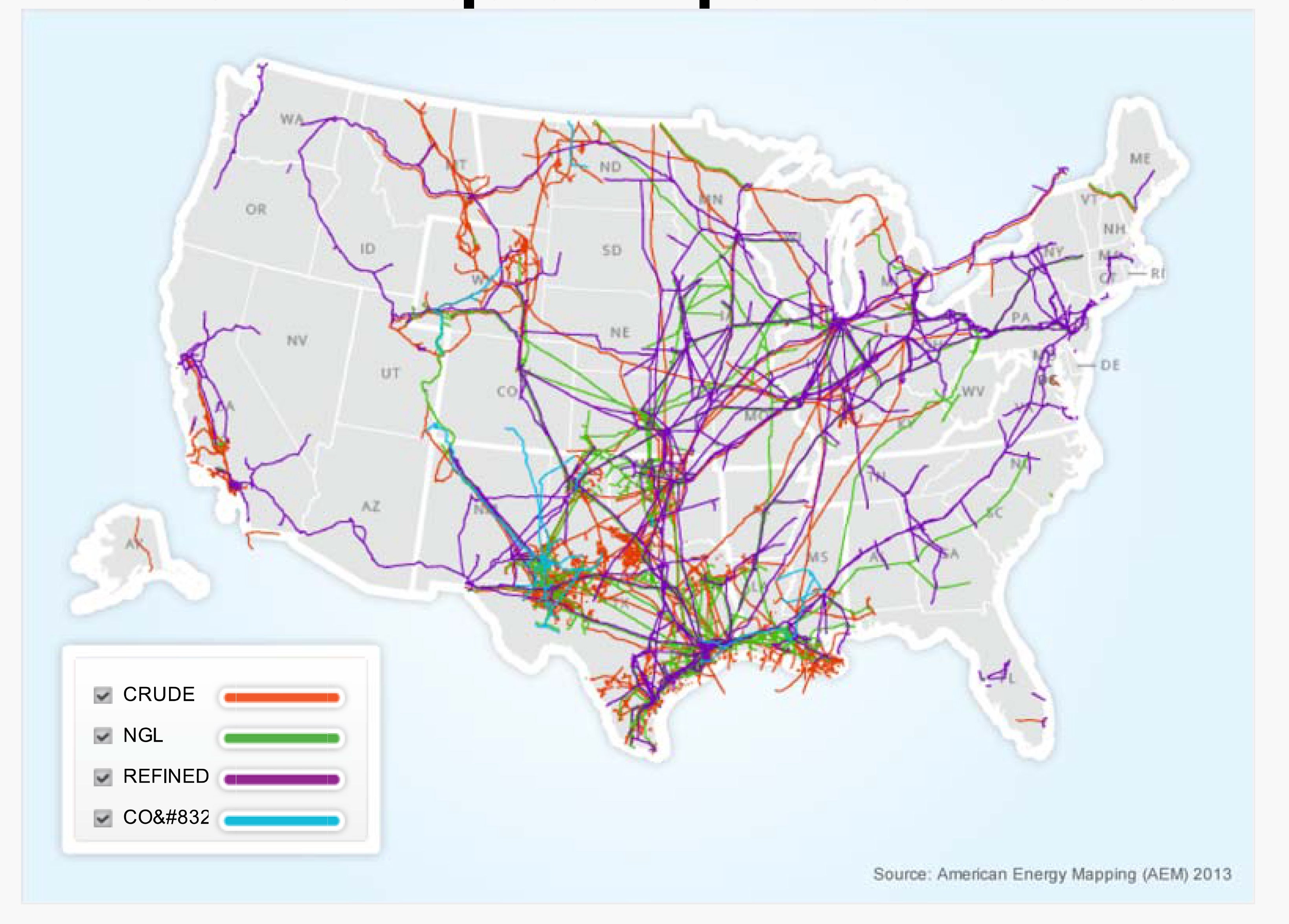

Map: Source: American Energy Mapping.