By John McPhaul

The brother of slain Bribri leader Sergio Rojas Ortiz, Jose Dualok Rojas Ortiz, said that the government should immediately remove non-Indigenous settlers from Bribri land and provide a system of security to protect Indigenous people living on the land.

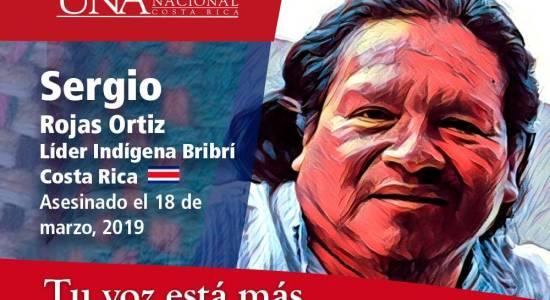

Unknown assailants shot and killed Rojas, 59, on Monday night, March 18, 2019, while he was in his home in the Salitre Indigenous Reserve in southwest Costa Rica. Sergio Rojas led a Bribri movement to reclaim land occupied by non-Indigenous settlers within the Telire Indigenous Territory.

"The government must order the immediate removal of the usurpers of Indigenous lands in compliance with Indigenous law and international conventions... return these lands to their legitimate owners-- the council of elders as established by international conventions and other laws, and immediately establish a system of security with precautionary measures to protect Indigenous Peoples... " posted Jose Dualok Rojas Ortiz on Facebook.

Jose Dualok Rojas Ortiz urged a respect for the rule of law. "The authorities enforce the laws, if they are not enforced it is for the interest of corrupt people and this is a cancer that only generates damage to the community and the country," he commented.

In a telephone interview, Jose Dualok Rojas Ortiz said that the government failed to adequately protect his brother despite an order of precautionary measures ordered by the Inter-American Human Rights Commission, “They had [police] there for 10 days and then they left, I don't know why," he said, adding that the crime should be investigated by international authorities. "Those responsible for the murder of Sergio Rojas must be judged. The government should assume its responsibilities. The laws must be enforced. No one can justify the purchase of land in Indigenous territory when the law says very clearly that this action is illegal."

In the 1970s, the Costa Rican government passed a law that established 24 Indigenous territories. Yet controversy arose when the non-Indigenous settlers on those lands were requested to leave without compensation. Many remained on the lands, and since then, other squatters have also settled onto the land.

The latest flare up began in 2012 when Sergio Rojas led a group of Bribri to occupy land in the Salitre Indigenous Territory and was met with violence by the settlers who burnt down their shelters and attacked the Indigenous protesters with clubs and machetes. Rojas argued that the Bribri should not have to live in slums in the regional hub of Buenos Aires when they have a right to live in their ancestral homelands. At the time, University of Costa Rica anthropologist Marcos Guevara circulated the idea that Rojas posed a threat to the status quo.

“Non-Indigenous people do not want a strong leader who has a purpose of recovering land,” said Guevara. “Rojas poses a special danger because he can inspire Indigenous members in other parts of the country to demand their rights for their lands.”

The Central American Regional Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a statement profoundly lamenting the violent death of the Indigenous leader. "Sergio distinguished himself for his struggle for Indigenous autonomy and the defense of the Indigenous territory of Salitre. He denounced the usurpation of land and the constant threats and aggressions against those who still continue struggling for their rights...We urge the authorities to take immediate actions to investigate, judge and sanctions the people responsible for his death as well as the guarantee the protection fo the people of Salitre -- just as established in the precautionary measures of the Integer-American Human Rights Commission -- and the protection of all the Indigenous defenders of Costa Rica," said the statement.

Gustavo Oreamuno, a representative of Ditsó Coordinator Lucha Sur Sur, said in the magazine Costa Rica News that Rojas' murder is not an isolated incident and that many outbreaks of violence by land grabbers have occurred over the years, since the process of land recovery by Indigenous people has increased since 2009. Oreamuno stated that "75 percent of the lands declared Indigenous are in the hands of persons of usurpers and the previous governments have not complied with the statutes of the Indigenous law and International Labor Organization Convention 169 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to deliver the lands that correspond to Indigenous communities."

Violence against environmental and Indigenous rights defenders continues throughout the world at an alarming rate. In an Op-Ed published last year by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Vicky Tauli Corpuz noted, “Human rights defenders, especially those protecting their communities’ lands and resources, suffer threats and attacks on a consistent basis. Last year, Global Witness documented at least 197 murders of land and environmental defenders all over the world. Historically around 40 percent of these murders have been indigenous people. And these numbers do not capture the full scope of the problem: the criminalization of indigenous peoples and killings in remote parts of the world that do not make news or reach reporters.At the root of this violence is institutionalized racism and discrimination.”

--John McPhaul is a Costa Rican-American freelance writer based in San Juan, Puerto Rico.