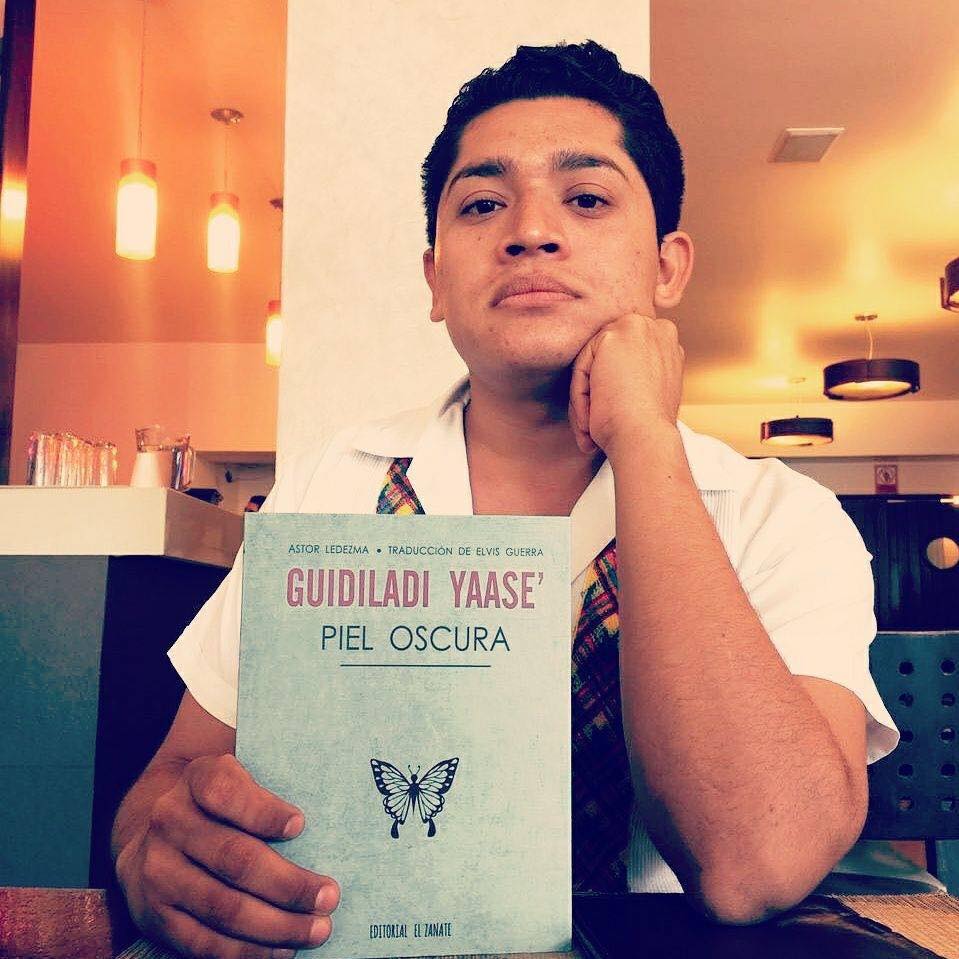

Elvis Guerra (Binizá/Zapotec) is 25 years old and lives in Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, Mexico. Cultural Survival’s Bia’ni Madsa’ Juárez López recently spoke with Guerra. Guerra is a fellow of the National Fund for Culture and Arts (FONCA) and a recipient of the CaSa prize for literary creation in the Zapotec language promoted by the painter Francisco Toledo, the Center for the Arts of San Agustín Etla, the National Council for Culture and Arts, the government of Oaxaca, and Editorial Calamus.

Cultural Survival: Tell us about you and your Peoples.

Elvis Guerra: I am a lawyer. I am also a poet, a translator, and I work in textiles. I have a team of women who work with me producing traditional clothing of Juchitán, which is a Binizá (Zapotec) town that is located in southern Mexico with just over 100,000 inhabitants. Most of us speak Diidxazá (Zapotec) and are practically bilingual. Our people are characterized by our social struggles and the defense of our rights. During the 1866 French invasion, and in 1974, when the movement of the COCEI (Workers, Peasant, Student, Isthmus Coalition) arose to end the monopoly of the former Institutional Revolutionary Party, it was women who spoke out and took up arms to defend the people. There is no doubt a fundamental role of women in our culture.

CS: Please comment on what it is to be muxhe, and how you participate in the community life.

EG: I try to capture the worldview and idiosyncrasies of my people through poetry. Many of my texts speak of characters from the community, especially the muxhes. Muxhe is a gender identity that has to do with men who are biologically born male and that over time adopt another gender different from their birth. Muxhes adopt exclusive roles of women; they are people who have sexual affinity with the same sex. Unlike gays, the muxhe community have very particular characteristics that have a lot to do with their sexuality in the way they exercise it. They may or may not be dressed as women. There is a historical rule that muxhes should be passive in a sexual relationship. There is no sexual or affective relationship between two muxhes.

For the Zapotecs there are four genders: woman, man, lesbian, and muxhe. There are no bisexuals, transsexuals, intersexuals, or asexuals; rather, everything else is defined from the muxhes. There are the muxhenguiu: muxhes that are men who do not dress as women, who sometimes decide to even marry a woman and have children, but perform socially feminine functions and that society identifies as a muxhe nguiu (man’s) body. There are muxhes gunaas, which are those that are assumed as women, who believe that their body should be that of a woman, who live and adopt the dress of a Juchiteca woman; the closest thing would be the trans. There are also the lesbian muxhes who break the aforementioned rules because they can relate to another muxhe, and have a love, dating, and sexual life. It is also called lesbian because it is the concept of two women together. Then comes a subcategory that has to do with women dressed as women who are active in a sexual relationship and are known as ramoneras. Ramoneras take the roles of men in bed. The name has a poetic origin; as it was a closed practice, muxhes could not be active, and they were the ones that broke the rule. The first man who turned was called Ramón. But since this cannot be named, the word Ramón was used as a form of euphemism, to say “there goes another one that turns around.” These are the peculiarities that have to do with the Zapotec culture and that make it different from Western culture.

CS: Following the idea of the Western classifications of pronouns, how do you prefer to be called?

EG: There are no genders in the Diidxazá (Zapotec) language. But when I speak in Spanish, for muxhes dressed as women, I use ‘la’ muxhe, and for those who dress as men, ‘el’ muxhe. I don’t care how they label me. I’m interested in having my rights respected.

CS: Juchitán is spoken of as the muxhe paradise. What’s your opinion?

EG: I’m still waiting for that paradise. It is a dangerous construction that muxhes have been part of. If it were a paradise they would not have killed Oscar Cazorla, Victor Corona, Adriana, and Lisa. This makes the other muxhes invisible; other names, other faces who are beaten, who suffer homophobia. We have a culture of more than 40 years defending the muxhes and they still kill us, beat us, stab us, spit on us, and yell at us.

CS: In a context where sexual diversity and human rights are discussed, where do muxhes enter this discussion?

EG: When I think of the LGBTQIA+ movement, I would like to add muxhes’ ‘M’ to the acronym, because it is very specific to our community and culture. We support the other expressions of sexual diversity because we are also a minority, because we are defending our right to life, and our right to love each other no matter whom. We are empathetic, but I think the LGTBQIA+ fight does not include us at all. Juchitán is a society where the roles are very marked. For example, during a party, women sit on one side, men on the other. If you go to the market, you realize that mostly women handle it. There are spaces where women can be, where they participate.

Who can sit with them? The muxhes. Who can engage in commerce? The muxhes, because it is mainly a women’s space. As muxhes are denied the right to school and other job aspirations, they do other activities such as handling decorations for traditional parties or cooking. Muxhes are mainly supported by women. Many women send their children, their husband, nephew, or uncle to buy from the muxhes, so this daily treatment makes the other normalize the muxhe. All of that helps make muxhes a little more visible. In Juchitán there is still the tequio, the mutual help. When someone dies, everyone cooperates, even if they have been fighting. Women go and cook and play their social role in a group.

CS: In other Indigenous cultures in the world, there seems to be no parallel with the acronym LGBTQIA+ (or muxhes). Why do you think that is?

EG: Many cultures still repress what they don’t think is on the level. I know people from other Indigenous cultures and ask them if there are homoerotic practices, and they answer, ‘Yes, but nobody names them;’ ‘Yes, but they are done in secret.’ I think that the Zapotec culture should serve as an example for others to free themselves. [At one time] the muxhes knew the right to go out without being violated, without being prey, for the simple fact of being muxhes. Right now the violence is unstoppable, but 20, 30, 40 years ago, the muxhes could not go out to meet other muxhes or dress as women because they would be taken away. Juchitán should be a reference point for other cultures to confront this system created from machismo, created from the binary, and thus defend what we are and what belongs to us.

CS: What obstacles have you faced in your community being muxhe?

EG: The first factor is access to education. When we reach primary school, we want to be women, put on women’s clothes, and the education system tells us, ‘No. Here are your shirts, pants, and shoes.’ Then many muxhes are forced to defect. I faced that challenge. Deciding between being a muxhe or a professional forced me to choose to be a professional. Now I do fully live my sexuality, but at the age of 8 or 9, while my mother, my grandmother, my grandmother, my brothers, my family allowed it, the educational system said no. I have learned that I cannot fight with the whole world, because what they say about me does not matter to me.

CS: What are your personal and collective goals?

EG: To grow as a merchant, to grow in textiles. My book is about to be released, it is called Ramoneras. I have three dreams in life, but I will reveal one. Before reaching my 30s, I dream of creating a home for muxhes—a house that serves as a school of arts and crafts for the muxhes that are excluded from state schools, so that they can learn a trade, and a house for old muxhes, a place where they receive food, a roof, love, a hug, from other muxhes so they do not feel alone.

All photos courtesy of Elvis Guerra.