I was born and raised in the western highlands of Guatemala in Xelajuj No’j. Five years ago, I embarked on a journey to learn my ancestral language as an adult. This journey has been difficult due to the disappearance of the K’iche’ language in the second generation of my family. My grandmother’s first mother tongue was K’iche’, and while my mother is able to understand it, she is unable to speak it. I am unable to understand or speak the language.

I remember having moments of confusion as a child when my grandmother, Abuelita Tonita, would not speak her native language in public. Instead, she would speak her ancestral language only in private spaces where she felt comfortable and safe. I remember listening to her speak K’iche’ with my great aunt, and it always confused me because she only talked to me in Spanish.

My mother explained to me that during the 1960s, my grandmother was told to speak to her children only in “Castellano,” the primary language spoken at the schools, to get a better job and become “generally better.” My Abuelita Tonita stopped transmitting the language not because she wanted to, but because of colonial development and economic practices and the education system in Guatemala that forced her to do so.

When I decided to learn my ancestral language at the age of 25, I faced some challenges that I imagine are common for most new learners. I felt I was not making any progress as I encountered overwhelming and complex grammatical rules. I had three different teachers who helped me understand the grammar and the structure of the language, but I am not anywhere near a fluent speaker; I feel it is because I am missing the immersion component. I need to be surrounded by the beauty of the sounds and the practical connection of the language with the environment.

During the pandemic, for the third time, I went back to classes via Zoom. The whole process was challenging and strange due to long hours of learning in a virtual space, the isolation of the pandemic, and learning the ancestral language through Spanish. Not only does being surrounded by the language make a difference, but so does investing a good amount of time each day. That’s the rule: there is no progress without investing an adequate amount of time.

I am still here today, recognizing what aspects I need to focus on to continue my journey and bring back the knowledge from my ancestors. I have concluded that I need to spend more time with fluent speakers and Elders and invest an adequate amount of time every day. It is a shame that it has taken me until now to realize how I could have learned more effectively when my family’s last two fluent speakers were still with us. But I am still here, and it is never too late to learn the language from the heart. Today, my mission is to reclaim the spaces where my ancestors did not feel safe speaking their language, to own my language and responsibly transmit it.

Mayan ceremonies at Lake Atitlan, Guatemala. Photo by Jorge Estuardo de León.

Restoring and Protecting Our Native Languages and Landscapes

On October 5–7, 2021, Cultural Survival held a three-day virtual conference, “Restoring and Protecting Our Native Languages and Landscapes,” gathering 31 Indigenous language revitalization experts and practitioners from Russia, Canada, the United States, Mexico, Guatemala, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Kenya, South Africa, and Australia. Three themes framed the event: Indigenous Languages as Contributors to the Preservation of Biodiversity; Reclaiming and Strengthening our Indigenous Languages Beyond Our Homes: Methodologies and Practical Approaches; and Indigenous Women and the Power of Community Storytelling.

The goal of the conference was to share knowledge and practical approaches around language revitalization efforts by Indigenous Peoples. After listening to the stories of Indigenous language warriors’ successes and struggles to keep their languages alive, I was inspired by the creative ways communities address their language revitalization challenges. I heard stories of how non-fluent adults can become fluent with a combination of financial and non-financial support; a well developed and culturally appropriate methodology; complementary resources such as digital media and written materials; and of course, the most important strategy— full immersion in the language.

During the presentations, Abuela Tonita’s words resonated in my mind when she spoke her language and referred to the meaning of the clouds and their shapes, the color of the sky, the days for harvesting, the meaning and use of medicinal plants, and the respect for corn and water. I remember her words very well, “we need to take care of what the land gives us. The land is our mother. One day there will not be water, and the children will have to face the consequences of scarcity.” Climate change impacts, including the lack of rains, have caused the loss of the families’ harvests, which means food shortages and higher prices. These factors, combined with the scarcity of water, could mean impending food crises for Indigenous families.

When I think about the risk of Traditional Knowledge not being passed down to new generations, I worry about how life and harmony among living creatures will continue. The languages are part of a whole. We cannot speak of the overall well being of Indigenous Peoples if our languages are not included.

In the words of Pertame language activist Vanessa Farrelly (Pertame Southern Arrernte), “the language is the voice of the land.” When we talk about the connection of Indigenous Peoples and the land, we talk about a whole living system that is interconnected and interdependent. This reciprocal relationship has a regenerative component. There needs to be a respectful way to interact with the land because the land feeds us and gives us life.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge contains valuable techniques and solutions to address, adapt, and mitigate climate change and biodiversity loss such as wildfires, floods, droughts, changes in animal behavior, and other alterations experienced on our lands and territories. This knowledge is intrinsically embedded and transmitted through the language, and, as Jeannette Armstrong (Syilx Okanagan), Associate Professor in Indigenous Studies and Canada Research Chair, pointed out during the conference, “when the knowledge is lost, the consequences are irreversible.”

Indigenous Peoples have adapted their lifestyle to respect the environment, preserving the forests, rivers, and lakes. The respect and caring for the land is especially transmitted through ceremonies, according to Marcus Briggs-Clouds (Maskoke), who emphasized the importance of talking to the land. When Indigenous Peoples care and preserve the environment, this relation upholds the life of flora and fauna species. “Language becomes the bridge in which Indigenous Peoples transmit the responsibility that comes with the knowledge,” said Antonio Q’apaj Conde (Aymara).

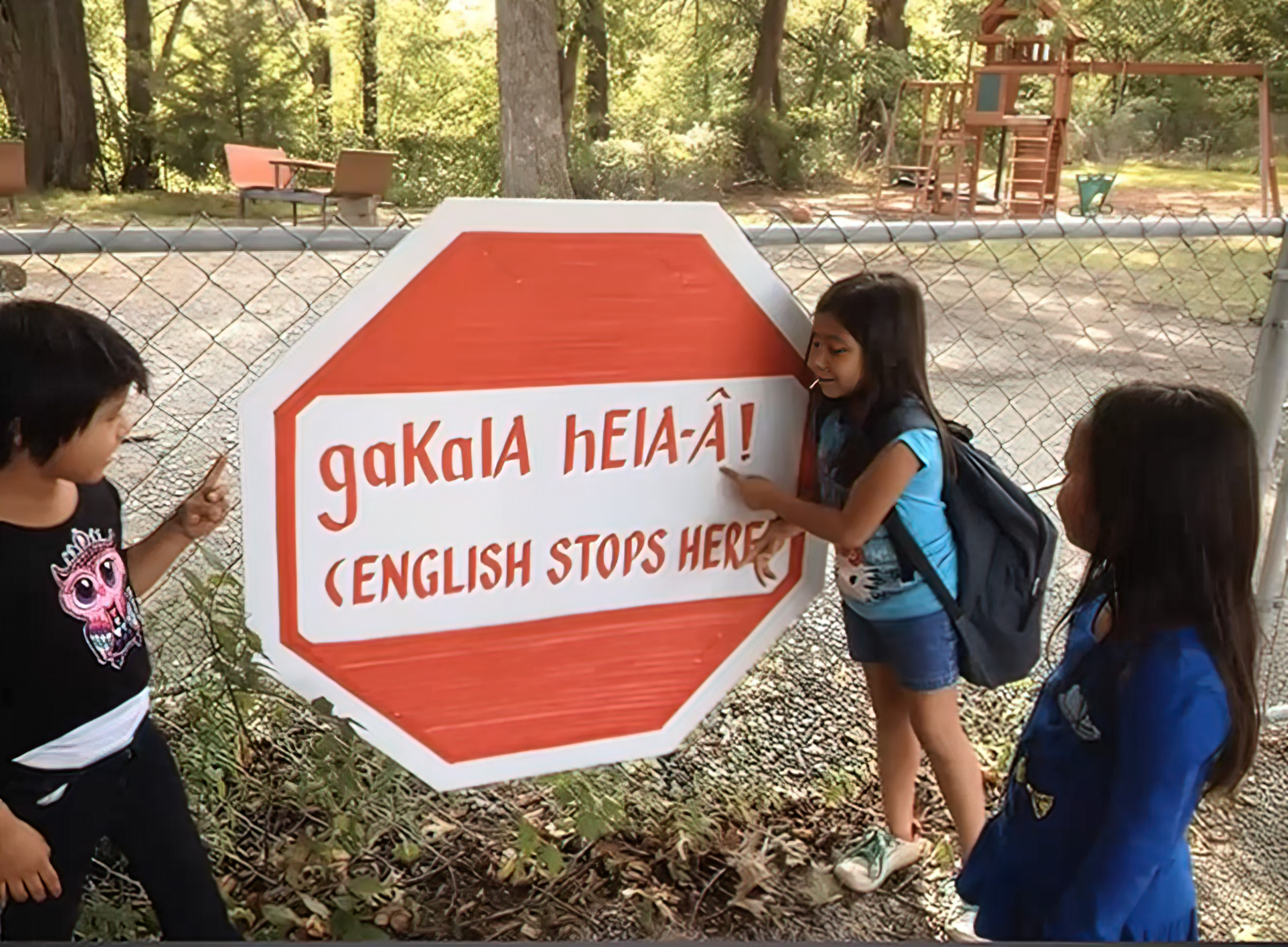

No English is allowed to be spoken at the Yuchi House in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. Photo courtesy of the Yuchi Language Project.

Challenges in Keeping Our Languages Alive

Prior to the conference, Cultural Survival conducted a survey that gathered input from 78 people attending from the following Indigenous Nations: Maya K’iche’, Tohono O’odham, Secwépemc, Waî Waî, Batwa, Nyindu, Guna, Hawaiian, Selkup, Maya Pocomchi, Dodoth, Ainu, Buryat, Maya Mam, Yoruba, Taino, Maasai, Stockbridge-Munsee, Lunaape, Mixtec, Yamaye Guani - Jamaica Hummingbird Tribe, Hñähñu, Rohingya, Hopi, Ngunnawal, Ngambri, Ngarigu, Moorish American, Oromo, Gunditjmara, Sunuwar, Tamoo, iTaukei, Chorotega, Dine, Sepik, Maya, Nama, Maya Kaqchikel, Syilx, Southern Ute, Chickaloon, Binnizá, Komi, Ayuuk, Tharu, Shoshone, Tŝilhqot’in, Xicanx, Guernsey, Cherokee, Garifuna, Gujjar, Chicana-Apache, Musqueam, Tunica-Biloxi, and Carpatho.

These attendees shared some of the barriers affecting their communities and their efforts to strengthen and revitalize their languages. Some of these include the relocation of communities to new territories; lack of information that enables them to ensure implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ rights to speak their language and their cultures; imposition and influence of official languages; lack of funding to support language programming and gatherings; false thinking that there is no “economic value” in the language; few Elder native speakers; colonialism, extractivism, and trauma; Western curriculum and methodologies; misinformation within communities; lack of financial support by funders; lack of engagement from youth; and spending time on activities with an academic focus rather than those related to language vitality.

Despite the challenges that were named, practitioners and experts in the field of Indigenous rights and languages revitalization shared inspiring stories demonstrating the urgency of taking action to recognize languages not only as part of the communication processes, but as an essential component of cultural identity, spirituality and cosmovision, and Traditional Knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples.

I believe that we as Indigenous Peoples must recognize the root causes of the loss of our languages. We need to work towards using our languages in the spaces that we have been denied for decades. We need to recognize the value of the languages and cultures and how our millennia-old Traditional Knowledge is embedded within these. And we must take immediate action to hold governments, State institutions, and policymakers accountable for upholding our rights, including the right to speak our languages in daily life spaces, especially in schools.

Rosa Palomino (Aymara), Vice President of the Network of Indigenous Communicators of Peru, Host of "Wiñay Panqara" radio program, and conference participant, conducts an interview. Photo courtesy of Rosa Palomino.

Solutions by Indigenous Peoples

Full immersion strategy

Indigenous Peoples globally create culturally appropriate solutions to keep their languages alive that are connected with their cosmovision. During the conference, I reflected on how complex other revitalization processes are when only a few Elder native speakers are still living. One good example of an Indigenous solution aligning with their cosmovision is the immersion methodology of the Yuchi Language Project in Oklahoma. This way of learning the language is quite similar to how we learn languages as babies. We listen, and with time we understand. No one explains all the grammatical rules that are usually taught in the Western education system. Understanding the grammar and structure of the language can be helpful, but most important is learning the language from the heart, what the sounds make us feel, and the connection that the language creates with what is around us.

The relationship between a mother and her children is reflected in the language. Indigenous women, as life-givers, have a tremendous role in transmitting the language from the womb. Halay Turning Heart (Yuchi, Seminole) shared how she assumed the responsibility of transmitting her Yuchi language to her children. Now her children are the first speakers of Yuchi as their first language in three generations. Like she said, “our ancestors have brought our language

this far, and now it is up to us to bring it home.”

Master-Apprentice Model

In a discussion of the Master-Apprentice Program, Farrelly explained how, due to the high level of endangerment of the Pertame language in Central Australia, it was necessary to recreate another generation of adult speakers with the support of Elders of the Pertame language. She expressed the importance of aligning her Indigenous values to the methodology to revitalize the Pertame language. “We’ve got to think back to how it was and our oral traditions. We just need to keep spreading the message and wake people up from thinking about it in Western ways,” she said.

Learning a language when you are an adult can be quite challenging, especially when you are in the intermediate level phase (when you can understand but are unable to have a highly fluent conversation). Michele Johnson, Ph.D. (Okanagan) from the Syilx Language House, highlighted the importance of dedicating time to learning a language. “You can’t expect people to revitalize the language on evenings and weekends,” she said. In cases where only a few Elders are teaching the language, there is a sense of urgency in investing more financial resources. By providing financial support to the adult learners, they will be able to invest more time doing the sacred work of preserving the language rather than being outside of the community for a full time job.

Multilingual Media and Digital Strategies

During the conference, it was emphasized that the immersion strategy is one of the most effective solutions to revitalize languages. Digital media is a powerful tool that can contribute to listening, reading, and practicing Indigenous languages more often. Community media is an effective mechanism to transmit languages and knowledge, especially when mainstream media only broadcasts content in the country’s official language. Socorro Cauich (Maya Yucatan), from Radio Yuyum, said, “There are many initiatives that do things in the Maya language related to language and culture, but if we do not get the word out, they will not reach those youth who are in those technological spaces.”

The proliferation of Indigenous languages in digital media must accelerate as the dominance of the English language in science and technology continues. The Ki’kotemal TV project is dedicated to reaching the children of migrants who have been forced to leave their communities and did not learn their ancestral language. Vianna Gonzalez (Maya K’iche’) explained that the project utilizes social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Youtube, Instagram, and Soundcloud, which has been very useful to upload content. Using technology to reach an audience that has had to leave their community and are not able to be fully immersed in the language can contribute to continuing contact with the language.

Generations of Saami reindeer herders in Russia. Valentina Sovkina (Saami), conference panelist, produced the film "Tsyya nita/Well Done Girl,” about a woman who revitalized her native language by speaking it with her granddaughters. Photo courtesy of Valentina Sovkina.

International Decade of Indigenous Languages

Although the steps to revitalize the languages are complex and require both financial and non-financial resources, at Cultural Survival, we are hopeful that “Restoring and Protecting our Native Languages and Landscapes” has become an inflection point to start a conversation in the upcoming Decade of Indigenous Languages with a focus on action. We do not want this decade to be another decade spent analyzing the issue around language loss, but rather to uplift and fund those communities doing the work and create more immediate results.

To this end, Cultural Survival advocates for a rights-based approach in which the communities doing the work have a say in the design and implementation of their language revitalization solutions. We, as Indigenous Peoples, have the responsibility to learn our languages and to transmit the knowledge that comes with them to our future generations. We have the right to speak our languages at school and in any public space. The revitalization of languages will be actionable when the solutions to protect, maintain, and strengthen Indigenous languages come from the Indigenous communities themselves and according to their values and cosmovisions.

We are hopeful that more funding will be dedicated to language revitalization work, primarily focused on grassroots initiatives. The priority should be creating new fluent speakers and speaking our languages again in public spaces. It is challenging to fundraise around the issue of creating new fluent adult speakers, as funders are currently incentivized to support programs that produce dictionaries and other written or audiovisual materials. These complementary tools can

help improve the use and understanding of languages as systems; however, in order to revitalize a language, it needs to be spoken.

For those who had to migrate and leave their communities, those who were part of boarding schools and were forced to stop speaking their languages, those who were told not to speak their language, the call is to leave fear aside. It is never too late to start the journey of relearning your Indigenous language. Some days you will feel that you are getting nowhere, but deep in your heart, you know you are doing something meaningful. Valentina Sovkina (Saami) expressed this idea best: “the most important thing is not to be afraid. There is an opportunity to learn. Our languages will live if you and your children can hear it and can speak it.”