By Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee Nation)

Lebanese-American author and poet Khalil Gibran is noted for his words declaring that, “There must be something strangely sacred in salt. It is in our tears and in the sea.” Indeed, extraordinarily diverse cultures and faiths the world over have long viewed salt with reverence and as a central part of life, survival, economy, and ceremony. Given its abilities to preserve, maintain, and enhance life, as well as purify and destroy, this substance is understood by many communities as a gift from the earth and an inseparable part of who we are as humans. Yet if any skepticism or uncertainty about the power and sacredness of salt remained, a visit to the Uyuni Salt Flat would surely put those doubts to rest. Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni, or Uyuni Salt Flat, is the largest salt flat in the world. A visit to the Uyuni Salt Flat is one where the senses are not only stretched but truly put to the test. This is particularly the case as the morning sun rises and gradually illuminates the entire salt flat, turning it into a blindingly white plane that stretches across the horizon without borders.

Moving over the Uyuni Salt Flat in a four-wheel drive vehicle with the windows rolled down, spotting a traveling parallel to us in the distance.

According to the traditional leadership of Marka Tahua who are some of the Pueblos Originarios, or original inhabitants and Indigenous stewards of the Uyuni Salt Flat, this plane of salt came to be as a result of the nearby volcano called ‘Thunupa.’ Thunupa was understood to be an extremely beautiful woman who married with a man named Cuzco. Together, they had three children. But Cuzco was not kind to Thunupa and mistreated her. This compelled Thunupa to leave Cuzco and her children even though she was still nursing her youngest child at the time. Fleeing to a nearby mountain, in her escape, Thunupa’s breastmilk spilled out and this white nectar was what became the Uyuni Salt Flat, forever solidifying the connection between this salt and the Thunupa volcano that stands at the flat’s northern edge.

Thunupa volcano and Uyuni Salt Flat at sunset.

The understandings of geology and science tell us that the Uyuni Salt Flat was created as the result of a massive, prehistoric lake that evaporated and dried over time. During Bolivia’s dry season lasting from April to October, the salt flat remains crystallized and is known for its blindingly white vistas. But the rains that come during the wet season months between November and March turn the entire salt flat into a massive pool of shallow water, acting as an otherworldly mirror to the sky and clouds above. The salt crust that comprises the top layer of the flat measures a couple of meters in thickness. It sits like a cap over a vast pool of salty brine below that is rich in minerals, including another powdery white substance that is particularly coveted by today’s society and industries: lithium.

Thanks to this mineral’s growing importance to global technologies, economies, energy demands, and attempts to combat the climate crisis, attention on the Uyuni Salt Flat has shifted in recent years from being a key tourism draw to now also being an epicenter of the extractive industry and South America’s ‘lithium triangle.’ Until recently, the town of Greenbushes in Western Australia had been the world’s top supplier of lithium where hard rock mining of the mineral dominates. Yet in the last couple of years, the various corners of the lithium triangle, including Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile, have begun to ramp up their production of lithium from within salt flats and highland desert landscapes that are shared across their borders.

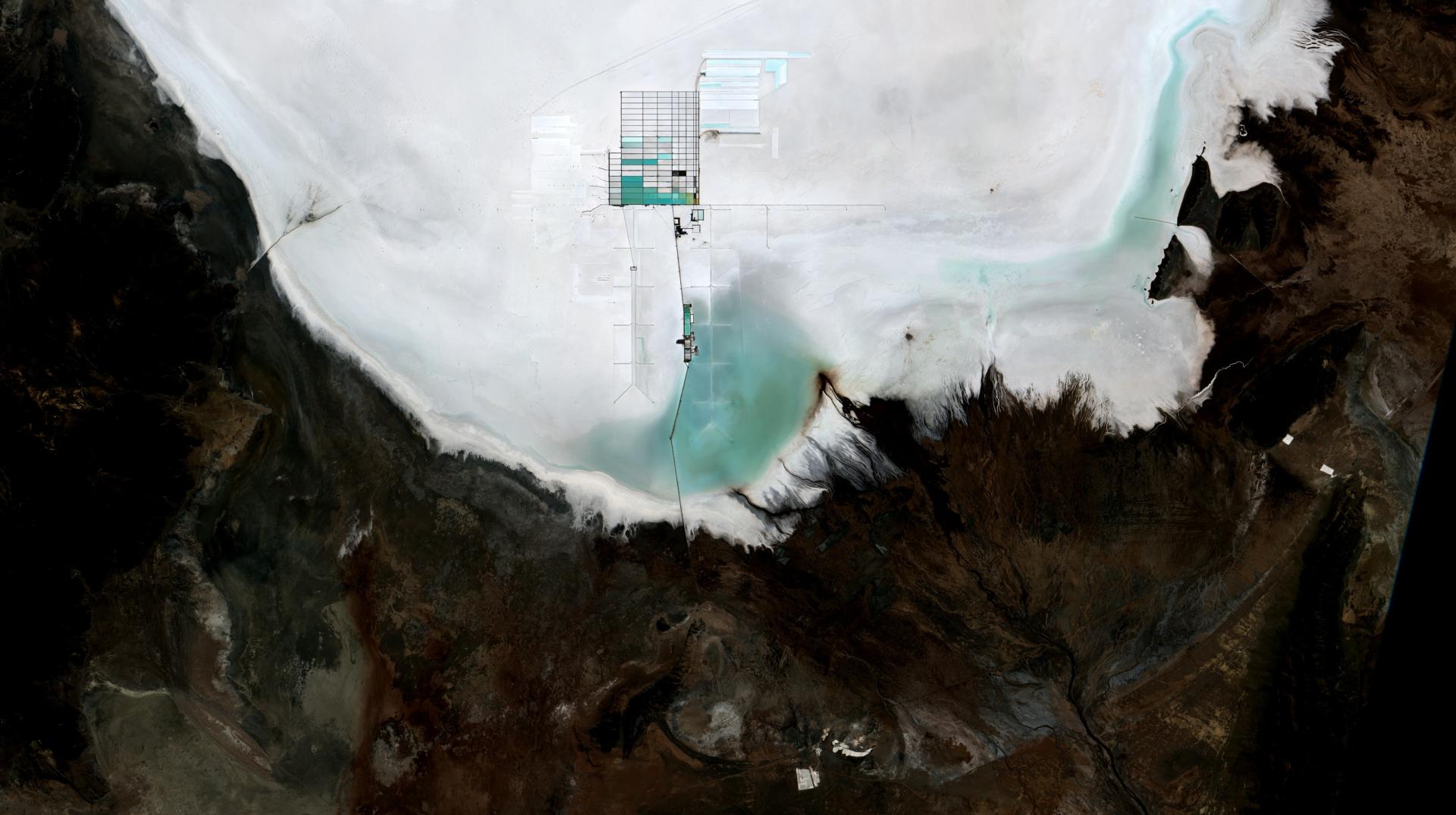

Unlike the technique of hard rock mining for lithium used in Australia, a process of extraction through evaporation is primarily used in South America. This lithium mining requires the lithium-rich, salty brine to be pumped to the surface from the underground layer where it is found. Once the brine is pumped into large collection pools, the sun, wind and the passage of time do the primary work as the liquid gradually evaporates and lithium is left behind. Aerial images of these evaporation ponds present a stark, eerie contrast to the natural, blinding whites of the salt flats and arid desert landscapes. These evaporation pools range across the color spectrum from turquoise and neon green to bright yellow and even pink depending on their stage of evaporation.

Aerial view of lithium evaporation at lithium mine at Bolivia´s Uyuni Salt Flat. Source Wikipedia.

Lithium is a particularly coveted substance in the efforts to decarbonize given that it is a primary mineral utilized for lithium-ion batteries and similar energy technologies that are powering everything from our smart phones and solar panels to electric vehicles and electric toothbrushes. Advocates of this process claim that brine pumping and lithium evaporation do not cause any type of contamination commonly seen with other forms of fossil fuel extraction and processing. Yet critics of this lithium extraction point to some glaring challenges and threats that this process brings to the fragile and extremely dry local ecosystems so unique to this part of the world. One of the primary problems is the amount of groundwater that is required to be used and pumped in the process—and the interconnection of this salty brine water to other freshwater systems and to all of the living beings that rely on these waters for life in these arid environments. This consistent usage of massive quantities of freshwater and underground water required for lithium extraction does not permit the water sources to be sufficiently replenished over time. At the current moment, no extraction technologies that are less water intensive exist at the scale required for industry in spite of efforts by some mining companies to research and develop them.

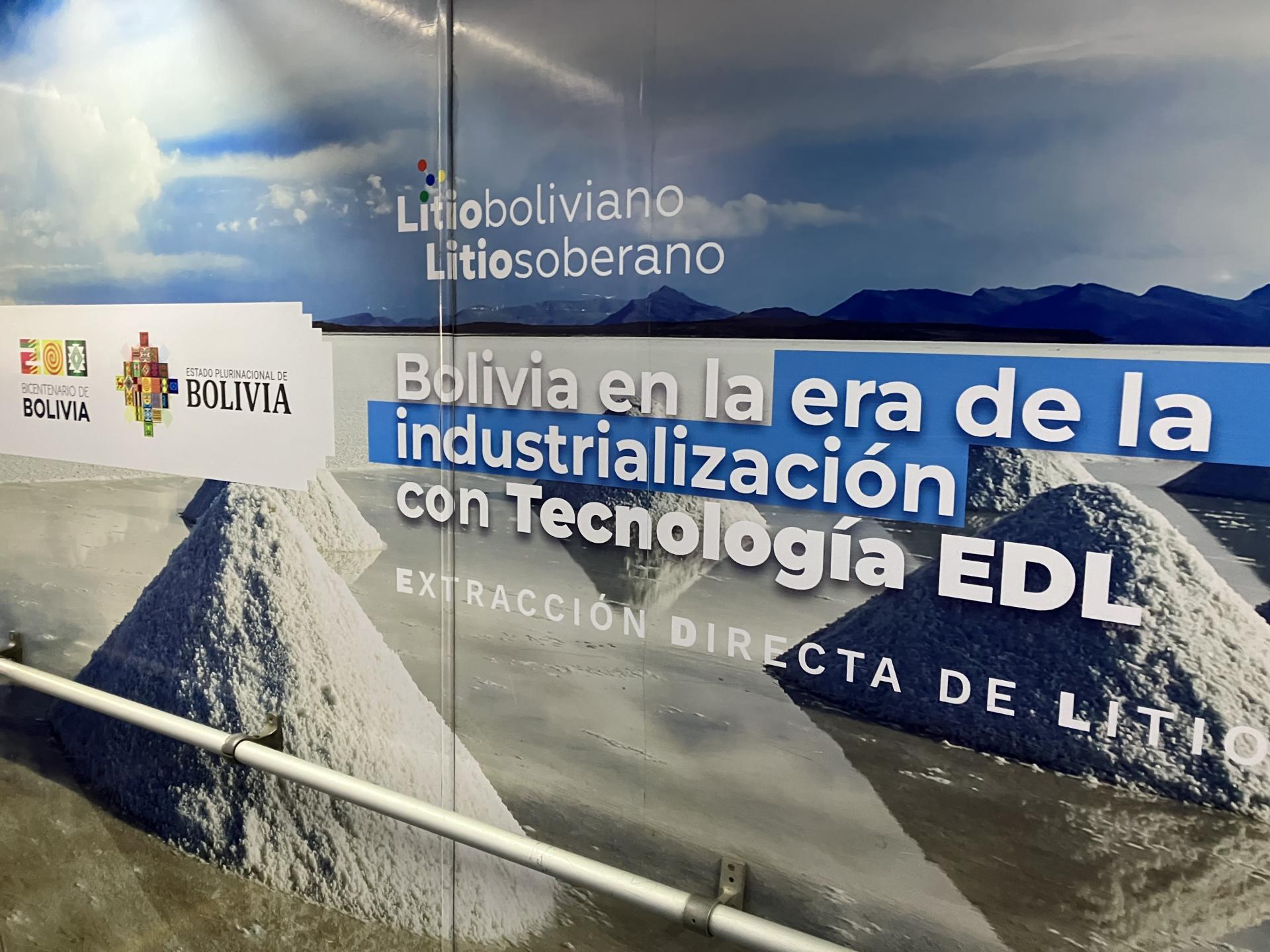

Mining is never far from any conversation or vantage point in this part of the world. Arriving to both the La Paz and Uyuni airports, billboards greet me at every turn and are constant reminders of the importance of lithium to the Bolivian government’s ambitions for economic and geopolitical strengthening. The US Geological Service has reported that Bolivia has more lithium than anywhere else in the world, estimated at approximately 21 million tonnes. As a result, the country’s journey of lithium extraction and industrialization began under former President Evo Morales who was in power from 2006 until 2019. Morales and his political party envisioned a future of Bolivian sovereign control over its lithium resources, with the ambition to eventually produce and export batteries. This led to state investments in a grid of evaporation ponds and an as yet uncompleted processing plant at the edge of Bolivia’s salt flats.

Billboard at the La Paz airport that reads, “Bolivia in the era of industrialization with Direct Lithium Extraction.”

An airport billboard in Uyuni that reads, “Lithium: We will industrialize the energy that moves the world.”

Another Uyuni airport billboard reading, “Lithium: We will industrialize the energy of the future.”

In spite of Bolivia’s massive lithium reserves, the lithium industry faces more challenges than lithium extraction in neighboring Chile and Argentina. These difficulties arise primarily from the fact that the lithium evaporation process leaves behind higher levels of impurities, as well as the barriers presented by the months-long rainy season that turns much of the salt flat into a shallow salt lake. Given these challenges and attempts to avert them, Bolivia’s state-owned lithium company entered into contracts with several foreign mining companies in 2023 with the aim to apply ‘direct lithium extraction’ techniques that do not require evaporation pools. However, some researchers assert that this technique has as of yet been unproven to work at scale. Among many local communities, uncertainty remains, particularly around the nature of the mining agreement details, water usage, and the feasibility of proposed plans to begin producing batteries by 2025.

Efrain Quispe Juarez, who is the Jiliri Mallku Pasmaru or traditional leader belonging to the Marka Tahua Aranzaya Maranzaya Yonza Council of the Original Autonomous Government, greets me at the Uyuni airport as I make my way past these lithium billboards. This year, Efrain and his fellow traditional leaders and community members of Marka Tahua were the successful recipients of a KOEF grant from Cultural Survival. Marka Tahua, representing 13 different communities spread across much of the northern border of the Uyuni Salt Flat, stands at the frontlines of this wave of lithium extraction. Efrain, as well as other traditional leaders and community members, are in opposition to the lithium mining and advocate for investments in the other industry that has been dominant in this area: tourism. The Tahua community has thus been using this KOEF funding to build their own cultural tourism infrastructure in the heart of the salt flat. And Efrain and I are heading to the frontlines to see these community ambitions in progress.

Efrain Quispe Juarez, at third from left, standing in the heart of the Uyuni Salt Flat alongside other traditional leaders of the Marka Tahua Aranzaya Maranzaya Yonza Council of the Original Autonomous Government.

Welcoming me to the city of Uyuni, Efrain takes me on a brief tour of the some of Uyuni’s key cultural and social landmarks, as this is the primary departure point for visitors aiming to travel to the salt flat. In addition to serving as a leader in the Marka Tahua traditional governance structure, Efrain is also a key community leader in Uyuni. In particular, in the neighborhood of Guadalupe, Efrain has been at the forefront of obtaining support for numerous community projects and infrastructure building, including the building and painting of a new multipurpose recreational court. He emphasizes to me the importance of these spaces and resources that serve to ensure that communities can stay strong in this area—and he asserts that the need to maintain and strengthen communities will be a key theme along the journey to Tahua and the salt flat.

With young children from the Guadalupe neighborhood at play in the background, Efrain stands proudly in the newly built multipurpose recreational court, called “Cancha Barra Chocolate.” The funds and services required for the construction of this sports court all came from local neighborhood community members.

On the car ride out of the town of Uyuni and towards the salt flat, we make a brief detour at Uyuni’s primary tourism draw—"the Train Cemetery”. The town of Uyuni owes its existence to the railways which served to export minerals from the surrounding mines of Huanchaca, including lead, zinc and at one time, silver. Wandering along the side of these abandoned train cars, some covered in colorful graffiti, Efrain says that the trains here are only a fraction of what stood there at one time. Driven by economic desperation, some people have stolen parts of the train cars to sell for scrap metal. The links between metal, mining and livelihoods are indeed an inescapable feature of this area’s historical and topographical landscape. After all, Uyuni is located within the state, or department (as it is called in Bolivia) of Potosí whose capital, the city of Potosí, was really where the story of mass mining throughout the Americas begins with the exploitation of Cerro Rico.

Tourists taking pictures at the iconic ‘Train Cemetery’ in Uyuni.

Heading in the direction of the salt flat, a blinding white vista slowly begins to come into focus from the distance and grows larger as we get closer. One of the main towns at the edge of the salt that serves as a key entry point to the Uyuni Salt Flat is the community of Colchani. There we stop briefly to speak with the traditional authority figure who greets us at the city plaza. In spite of being a prime ‘gateway’ to the Uyuni Salt Flat, Colchani feels largely abandoned, with few young people and only a small row of vendor booths selling items for tourists. Efrain and the Colchani traditional authority figure discuss their dissatisfaction with the proposed ‘economic solution’ for this area—the possibility of lithium mining and processing. According to them, the primary lithium company had said that they would offer employment to locals from communities such as Colchani, but as of yet most people at the lithium plant are not locals and have been recruited from other areas of Bolivia. Both men agree that increased investment and support for training and equipping locals to be part of the tourism economy is what they prefer—and as I will come to learn over the next days, a broad consensus of opposition against lithium extraction is voiced from traditional leaders and community members alike.

Meeting with Colchani’s traditional authority figure and speaking about the economic, social, and environmental challenges facing Colchani community.

Leaving Colchani and embarking onto the salt flat, it is clear that wearing sunglasses is as imperative as breathing. The sun overhead turns the salt plane into a glowing and blinding expanse of crystal white light, with the occasional sparkling of individual salt crystal clusters that draw attention. The initial edge of the salt flat that we cross in the four-wheel drive has a thin pool of water on top, but it does not take long until our vehicle is gliding along on the dried salt. Quipse turns around to tell me, “This is not normal. We are in April, the rains have recently stopped, and normally the salt flat should still be covered in a pool of water. But as you can see, most of that water has dried up. We are already seeing the impacts of water usage on our rain and water cycles here on the salt flat—and there’s little doubt that this water usage is a result of the extractive industries. It is not only our communities that are impacted by this change in water, but also the other creatures that live on the salt flat, such as our native Andean flamingo. Less water and food sources are left for these animals. We are seeing fewer and fewer of these birds, as well as other creatures of this landscape, and that makes us concerned.”

Tire tracks at the start of the Uyuni Salt Flat where much of the previous wet season's rainfall has evaporated.

Deeper into the salt flat, our driver Mario makes a stop at a different point of water that stands as a break in the white crystal plane. Hopping out of the vehicle, it is quickly apparent that this is not a pool leftover from rainfall, but instead is a natural ojo de agua, one of several springs of salty water that bubbles up from below the salt flat surface. As with nearly all of the features in this landscape, Efrain and Mario immediately show reverence for this area, explaining to me the imperative to greet this spring and honor it with a ritual act of showering it with gifts of inalmama, coca leaves, and jhank’o huma, pure alcohol. I soon come to learn that this same ritual process of asking permission upon entry and departure, showing respect, and gift showering is one that will be repeated 13 more times for each of the different communities that comprise Marka Tahua. This process is how it has always been done among Aymara people in this area and is the right way to establish and be in good relation with all beings that come into your path. But for now, as the sun begins to set over the salt flat, we head straight towards the volcano of Thunupa and the community of Tahua that sits at her base on the salt flat’s northern edge. Tahua will be our base where we are hosted for the next nights. It will be through the eyes of Tahua leaders and community members that we begin to learn about all the unique and incredible features that the salt flat has to offer in serving as a homeland and not just as the world’s next big source of lithium.

A salty water spring in the heart of the flat where salty water bubbles up.

Efrain speaks to the spring, offering an introduction and showering of inalmama, coca leaves, to mark our presence, as Mario, our driver and local community member looks on.

Inalmama, coca leaves on the salt flat that have been offered to the spring.

Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee) is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, where she researches the intersections between Indigenous-led tourism and resurgence. This article is part of a series that elevates the stories and voices of the Indigenous communities and land defenders in the Lithium Triangle.

Read: Reclaiming Sovereignty Through Salt and in Spite of Extraction: A Journey to Ayllu Yaribay