Indigenous languages are more than forms of communication. They are reservoirs of Traditional Knowledge generated and sustained by the Earth, expressed through a Peoples’ cultural, linguistic, and ecological practices and reflecting an interdependence between human wisdom and the natural world. They are living, co-evolving knowledge that transcend generations and play a fundamental role in protecting socio-biodiversity and addressing climate change.

The correlation between linguistic and ecological diversity is a profound manifestation of cultural diversity intertwined with ecosystem resilience. New Guinea is known for having great linguistic diversity, around 800 languages, and for harboring vast biodiversity, with 13,634 cataloged plant species. The Amazon basin, home to hundreds of Indigenous languages, has an equally rich biodiversity. These areas of high linguistic diversity sustain traditional ecological practices vital for environmental conservation. This correlation is because each language and culture carries specific practices and knowledge of environmental management to balance and regenerate local ecosystems.

A 2020 UNESCO report states that approximately 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity is on Indigenous territories. These areas are vital for environmental conservation, sustained by practices transmitted through language and orality. Indigenous languages carry an immense heritage of ancestral knowledge about local ecosystems. Indigenous communities that keep their languages alive more effectively implement sustainable management practices and detect subtle environmental changes. This Traditional Knowledge contributes inestimably to conserving areas with high biodiversity and adaptation to climate change.

Colonialism, combined with the expansion of extractive megaprojects, has accelerated the degradation of local microclimates, devastating Indigenous cultures, languages, and worldviews. Indigenous languages constitute inventories of species, classification systems, and forms of managing diversity—fundamental technologies for safeguarding and restoring the environment.

THE BEEHIVE OF TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE

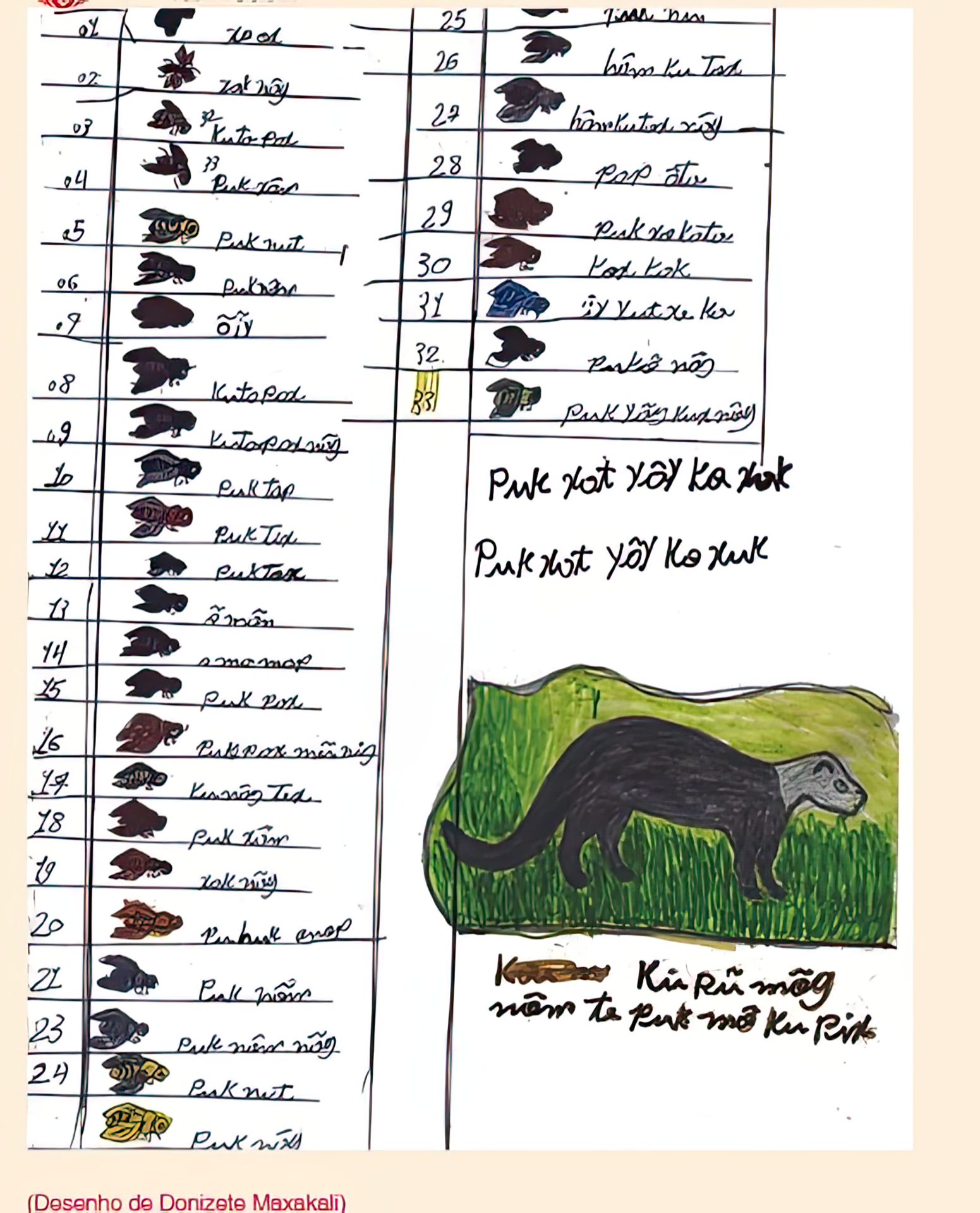

The Tayra song of the Tikmũ’ũn/Maxakali Peoples, which catalogs 33 species of bees, shows how an Indigenous language can safeguard vast biodiversity knowledge. These chants function as preservation technologies and transmit ancestral knowledge centered on orality, repetition, and collective ritualistic practice, reflecting the deep relationship between the Tikmũ’ũn and their natural environment while directly influencing environmental management and the protection of bee species in the region. By recording and transmitting each species’ different names and characteristics, the Tikmũ’ũn maintain a monitoring of the balance of local ecosystems, enabling sustainable and harmonious management.

A traditional chant of the Tikmũ’ũn Peoples in the Maxakali language catalogs 33 species of bees. Drawings by Donizete Maxakali.Image courtesy of Instituto Opaoká.

The song advocates sustainable interactions with bees, promoting actions that avoid overexploitation and encourage the conservation of hives as well as solitary bee nests, ensuring pollination and, by extension, biodiversity in the region. Collective voices call upon the bees as they recreate the sound of the swarm in a mix of song, canon, and counterpoint. The Tayra song of the Tikmũ’ũn Peoples is an ancient technology that safeguards ecological knowledge while also concretizing the symbiotic relationship with nature, demonstrating how Indigenous languages act as tools of resistance and transmission of environmental knowledge.

LANGUAGES AND BIODIVERSITY: A VITAL INTERCONNECTION

The Kayapó Peoples also use an extensive, specific vocabulary to describe and interact with their environment, highlighting the diversity of linguistic practices that encode detailed ecological knowledge across different communities. Specific terminology in Kayapó is essential for transmitting sustainable management practices and biodiversity conservation that are largely unknown to Eurocentric culture, reinforcing the argument that Indigenous Peoples are the greatest experts on biomes. These practices emphasize the richness of knowledge transmitted through Indigenous languages and the importance of strengthening them to maintain sustainable management practices and biodiversity. The linguistic detailing of the Kayapó to describe rivers and vegetation exemplifies how this knowledge is fundamental for conservation, mitigation, and adaptation strategies to climate change.

The interrelationship between climate change and endangered Indigenous languages is complex and deeply intertwined. The intensification of climate change increases the vulnerability of Indigenous communities, exposing them to forced displacement, loss of territories, genocide, and environmental degradation of traditional lands. These factors, in turn, directly impact the survival of native languages, which depend on their geographic and cultural context to be transmitted integrally.

VALE DO JEQUITINHONHA: TERRITORIES OF RESISTANCE

The loss of access to ancestral lands has profound consequences for the essential oral practices of Indigenous communities, such as ceremonial songs and narratives about sustainable resource management. The imposition of violence based on racism has made speakers of these traditional languages feel ashamed of their own identity, leading to the loss of these oral traditions by forced choice or intergenerational ethnic trauma. These practices, in addition to safeguarding cultural identity, store detailed knowledge about the sustainable use of plants, soil maintenance, and water resource management. With the interruption of territorial access, the transmission of this knowledge is compromised, weakening the capacities for sustainable management and ecological adaptation fundamental in the face of climate change.

One observable case are the Aranã Caboclo Peoples, who, once deprived of their territory and subjected to linguicide, have been fighting for the defense and recovery of their land in a legal battle against the Brazilian State that has dragged on for over 19 years. At the same time, the Aranã Caboclo have maintained a project of “linguistic reforestation” of the Aranã Caboclo language and actively combat ethnic shame. They fight to maintain ancestral knowledge deeply rooted in the territory, such as the Aranã Caboclo Tubercle, whose leaders maintain knowledge of various species and monitor their growth, even though the territory is not officially demarcated the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI). The vulnerability of Indigenous languages, exacerbated by the continuous invasion of territories, racism, and cultural homogenization, compromises the transmission of crucial knowledge.

The advance of lithium mining in the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys presents another threat to the Indigenous communities in the region. Mining activity has increased 562 percent in the last 2 years, reducing the vital space where cultural and environmental practices are maintained. This advance inhibits the rituals, songs, and narratives that transmit essential knowledge, harming sustainable practices linked to language and territory. The Aranã Caboclo, Pankararu, Pataxó, and Maxakali Canoeiros Peoples suffer from deforestation and water contamination, which threatens the oral transmission of knowledge about flora, fauna, and environmental management, further increasing their cultural and socio-environmental vulnerability.

THE PAST IS INDIGENOUS AND THE FUTURE IS, TOO

Local knowledge, especially that of Indigenous communities, provides a foundation for strategies to mitigate the climate crisis in its intrinsic harmonious coexistence with the ecosystem. This knowledge is centered on environmental management that respects the rhythm of nature, the sustainable use of resources, and the protection of forests and waterways—practices that are fundamental to halting biodiversity loss and climate imbalance. The Aranã Caboclo communities of Araçuaí and Coronel Murta, Pankararu, Pataxó, and Maxakali are just a few examples of the resilience and holders of vital knowledge that need support and recognition to ensure a more balanced and sustainable future for all.

The revitalization of Indigenous languages is essential for environmental sustainability and for mitigating the effects of the climate crisis. Indigenous languages harbor inventories of species, classification systems, and forms of managing diversity, fundamental technologies for the protection and biorestoration of the environment. Linguistic loss implies the loss of decisive knowledge to face the contemporary climate and environmental crisis.

Protecting Indigenous languages protects forests because Indigenous Peoples are the living forest itself. Defending their languages is to defend the deep connection between culture and land, ensuring that the language of the Earth continues to resonate. The loss of these languages implies the loss of essential knowledge to face the contemporary climate and environmental crisis, as these voices carry ancestral knowledge capable of guiding life with the planet toward the only possible future for all of us.

Djalma Ramalho Gonçalves (Aranã Caboclo) is a multiartist and grassroots communicator.