Nicaragua is a multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual nation. Internally it is divided into 16 departments, nine regions, and three special zones. In 1987, with the proclamation of a new political constitution and the approval of the Statute of Regional Autonomy of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua, the eastern coast of the country (referred to in the legislation as the Atlantic coast, but on a map it would be labeled the Caribbean coast) was divided into two large autonomous regions, north and south. The south region is made up of nine municipalities, the north of six municipalities.

The Autonomy Statute recognizes distinct rights and responsibilities for the inhabitants of the two autonomous regions, including the right to education in their own language; the use and enjoyment of the waters, forests, and common lands; the preservation and development of their languages, religions and cultures; the right to vote and be elected as the proper authorities of the autonomous regions; the rescue and promotion of traditional health knowledge; the right of the people to choose their own ethnic identity; and the right to administer justice.

It is important to mention that the weather of the Caribbean coast is tropical and humid, with a high degree of biological diversity and abundant river and forest resources that support forestry, mining, and fishing. Along the Pacific coast and in central Nicaragua, due to the mestizo culture, there are practically no forests.

The Caribbean coast represents 42 percent of the national territory, and the indigenous groups and ethnic communities who live there—Miskitus, Sumus/Mayangna, Rama, Garifonas, mestizos and Creoles—represent approximately 12 percent of the national population. We indigenous peoples maintain our own languages and territories, natural forests, and culture. The rights we enjoy have been achieved through several battles since 1860—since the formation of the Moskitia Reservation. Even the Law of Autonomy was passed in 1987 only after an armed battle. This, of course, has been the struggle of indigenous groups and ethnic communities all over the world, who seek to live with dignity as human beings.

That is why I would like to quote the Autonomy Statute of the Two Regions of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua:

The New Constitutional Order of Nicaragua establishes that the Nicaraguan Nation is multi-ethnic; it recognizes the rights of the communities of the Atlantic Coast to preserve their languages, religions, art, and culture; the use and enjoyment of the waters, forests, and community lands; the creation of special programs that contribute to its development; and the right of these communities to organize and live under the ways that correspond to their legitimate

traditions.

In addition, Heading IV of the Patrimony of Autonomous Regions and Common Property, in Article 36, states:

Community property means the land, waters, and forests that have traditionally belonged to the communities of the Atlantic Coast, and they are subject to the following dispositions:

1) Community lands are inalienable; may not be donated, sold, seized, or taxed; and are imprescriptible.

2) The inhabitants of the communities have the right to work the lands in the community property and to own the product generated from such work.

Article 11 states, as well, that:

The inhabitants of the communities of the Atlantic Coast have the right to absolute equality of rights and responsibilities regardless of their population and level of development.

This legislation has received much acknowledgment and has provided legal protection, which, in turn, allowed the Awas Tingni community to go to the local, national, and international authorities to claim their right as a nation to be heard. The Awas Tingni have been ignored and discriminated against for centuries; our gratitude goes to those local, national and international authorities that listened to our people’s voices.

In 1998, the Awas Tingni brought suit against the government of Nicaragua in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IDH) for not demarcating the Awas Tingni lands and for allowing logging concessions to operate on those lands. In 2001, the court ruled in favor of the Awas Tingni and required the state to define and protect the communities’ lands and also to pay restitution and court costs. But Nicaragua has failed to implement the judgment dictated by the court.

The judgment was issued on August 21, 2001, but months after, when our community and its advisors requested a first conversation with government representatives, they treated us in an unpleasant manner. The community and its advisors had several negotiating meetings with government representatives, with the intention of enforcing the judgment. However, in every meeting they always brought up the fact that they would be giving the community a title deed under the Agrarian Land Reform Act. The community did not accept this proposal. Our fear was that being the first community that demanded deed titling, we would create a precedent that could be applied by the government in the deed titling of other communities.

Fifteen months after the judgment notification, the Law of Community Property by Indigenous Groups and Ethnic Communities of the Autonomous Regions of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua and the Bocay, Coco, Indio, and Maiz Rivers was passed. In January 2003 this demarcation law became effective, and under the rubric of that law, the government unilaterally broke negotiations with the community and its advisors, referring the Awas Tingni case to local authorities, which were creating their own organizational structures, such as the Inter-Sector Commission of Demarcation (CIDT) and the National Commission of Demarcation and Title Deeds (CONADETI).

At that moment, the government demanded a community diagnostic, which was performed by a national nongovernment organization. This diagnostic clearly confirmed our ancestral use of the community land. With this diagnostic, we requested that the Inter-Sector Commission of Demarcation proceed with their study and refer the case to the CONADETI. Our request remained at the CIDT for 12 months, since the CIDT did not yet have internal procedures regulations. Only then did the CIDT take the case, which was discussed at length and then referred to the CONADETI.

Once the CONADETI received the resolution from the CIDT authorizing the deed titling, the CONADETI stated that the Awas Tingni case should have been referred to the Demarcation Commission of the Autonomous Regional Council, arguing that it presented overlapping issues with neighboring communities. But before the Demarcation Commission could reach a decision, a deadline for conflict resolution expired. Nonetheless, the community demanded that the authorities enforce the CIDT resolution, but neither the CONADETI nor the Demarcation Commission agreed.

The Demarcation Commission has mediated two negotiating sessions between Awas Tingni and the representatives of the neighboring communities. But CONADETI has not had the appropriate methodology to handle this negotiation, and for this reason the Inter-American Court’s judgment still has not been implemented.

I would like to stress that the central government has power over the regional authorities. We feel that because we demanded a hearing and won against the government before an international tribunal, the government is now retaliating against the community. For the same reason we think that CONADETI authorities excluded the Awas Tingni when other communities were given the first title deeds in May 2005.

My community and I will continue to struggle until we achieve the demarcation of our ancestral territory. At this time, we are at a standstill in the demarcation process due to internal conflicts of the CONADETI, which in fact have caused a temporary freeze of its operating resources.

We feel that the judgment has not been sufficiently digested by the national and regional authorities, that there is a general ignorance of the judgment, and that this has caused the delay in its implementation. The community feels that permanent monitoring by the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights is necessary to achieve the demarcation of Awas Tingni.

We feel that there are holes in the autonomy statute, and that when authorities interpret this norm, they do it their own way. It is possible that these authorities might not be clear as to what the law tries to achieve, from the perspective of indigenous communities: the demarcation of the land, and with it, the enforcement of the fundamental human rights of the Awas Tingni community. As anthropologist Rodolfo Stavenhagen stated very accurately in his testimony before the Inter-American Court, “The majority of indigenous groups in Latin America are groups whose essence derives from their relationship with the land, as farmers, hunters, collectors, fishermen, etc. Their bond with the land is essential to their identity. The physical, mental, and social health of indigenous groups is closely related to the concept of earth. Traditionally, the communities and indigenous groups of the different countries of Latin America have had a community concept of land and its resources.”

Our community understands the realities of state politics, but we suggest as a nation, that when these cases are dealt with, they should be considered fairly. At this moment, the Awas Tingni case is at stake, especially because it needs political will in order to achieve its effective implementation.

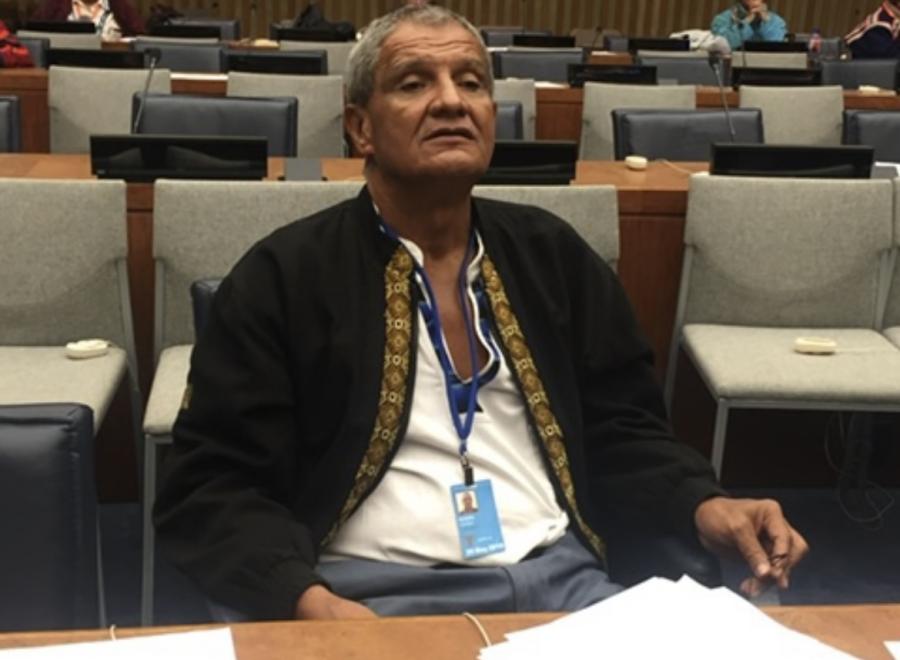

Esther Melba McLean Cornelio is a leader of the Awas Tingni.