The Ponca Nation has lived on the reservation near Ponca City, Oklahoma since the federal government moved the tribe from Nebraska in the 1870s. Ponca City is also home to corporations, factories, and oil refineries that contaminate the environment with toxic chemicals. The fish in the Arkansas River, an important food source for the Ponca people, have been dying, and the Ponca Nation is suffering from abnormally high rates of cancer. Meanwhile, the city has placed the municipal dump on a Ponca burial site. Such actions are what Mekasi Horinek, member of the Ponca Nation and coordinator of Bold Oklahoma, calls environmental racism. In spite of a victory in a class action lawsuit against the Taiwanese Continental Carbon Company, a plant causing carbon black emissions, the tribe does not have adequate resources to pursue further legal action. Horinek recently spoke with Cultural Survival, discussing the impact of pollution on the Ponca Nation, actions that can be taken to make a difference, and what the future holds for the community.

Cultural Survival: What are the sources of pollution affecting your community?

Mekasi Horinek: The reservation, our main community, is about five miles south of the ConocoPhillips refinery on our land. We also have the Carbon Black Continental Carbon factory, which takes from the refinery. We have the Ponca Iron and Metal factory building just south of the refinery near our community, and we’re receiving a lot of pollution from that, fires burning, smoke all the time. We also have the Ponca City municipal dump which is located on the same hill as our burial ground. There is a waste management facility that treats raw sewage north of our community on the banks of the Arkansas River. [So] there is a lot of environmental stress in our area, and the pollution that comes from all of these is very detrimental to our people. We have very high rates of different types of cancer, leukemia, lupus, and also a lot of things with the children and the elders—and not only our community, but the city of Ponca City—you know they’re suffering the same as us.

What efforts have been made to clean up the river?

MH: There have been no efforts to clean it up. As far as the river goes, we’ve had eight fishkills in the past four years and the EPA has done testing on the water, but they say they don’t know where exactly the pollution is coming from. The tribe doesn’t have the resources to do an extensive cleanup. I can pin the pollution in the rivers directly to the fracking industry; I know that they drain water out of the river, putting waste water back in the river. Why have the EPA and government entities failed to identify the source of the pollution? MH: We know that the oil industry feeds the economy in Oklahoma, and I guess you would say there are allowances they give the oil industry that they might not give other industries. The salt water content at the time of the fishkill would be one source, so the EPA saying that they couldn’t identify the source of the pollution was just blatant disregard.

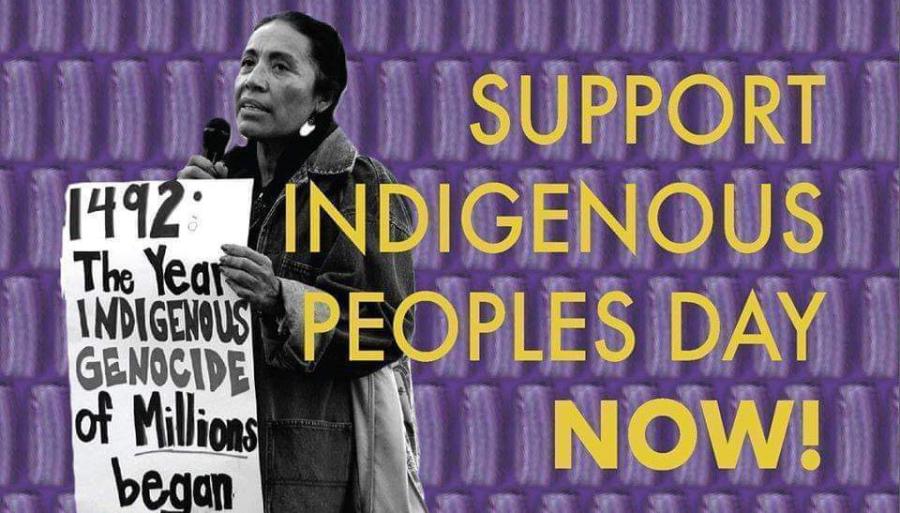

What does the term “environmental genocide” mean, and how does it apply to this situation?

MH: There are two terms that I would like to talk about: environmental racism and environmental genocide. Environmental racism has been going on for many, many years in our area. Ponca City zones everything to the south side of town, which is where the reservation is. The refinery, the carbon plant, the Ponca oil and waste facility, solid waste treatment plant, the sewage plant, the dump, are all on the south side of town. They don’t put anything that’s toxic or bad for the people on the north or east or west sides of town where the more prominent citizens are. The south side of town is the low income side of town, with white people, black people, hispanics, and then the reservation. The fact that the city hasits municipal dump on our burial ground, the most sacred site on our reservation, is definitely environmental racism. As far as environmental genocide, we have a tirade of cancer in our community, and not only in our community but in the community of Ponca City. I have a 16-year-old son and a 14-year-old son. One of my 14-year-old’s classmates died last year, and one of my 16-year-old’s classmates is dying of cancer right now. I don’t think there are any families that have not been touched by cancer. That’s why I say that it is a form of genocide. Just in my family alone, my dad is a cancer survivor, my uncle just passed away from cancer about two years ago, my son’s classmates have cancer, and a lot of women in the tribe have had different types of cancer as well.

Besides the class action lawsuit against the Taiwanese Carbon Black Plant, have any other legal measures been taken to hold the sources of pollution accountable?

MH: No. The class action lawsuit against the Carbon Black facility was actually won, but there weren’t long term medical benefits given to those people. So the people had enough money to relocate and move, but are still suffering from the health repercussions. There haven’t been any other lawsuits brought against Ponca City for environmental racism or ConocoPhillips Corporation for environmental genocide. I hope that is something I see happen in the near future.

What can be done to address the possible long term risks of the pollution?

MH: I definitely think that the media can help. It’s kind of taboo to think about in this oil state of Oklahoma. Getting the word out and bearing witness is definitely one tool that we can use. One of the things that is hard to grasp is the carbon credit. They talk about carbon credits, that they buy carbon credits and they plant trees in Australia, or they take care of a certain area in the Amazon which permits them to put out more pollution here in our country, where we live. That’s something people need to be aware of, because people think that carbon trading and carbon credits are a really good deal, that these corporations are putting money into conserving rainforests and conserving trees in different areas to try to offset the change. But what it does is give them the opportunity to put out more pollution in the areas where they’re at, and it’s detrimental to my people.

How does the environmental contamination affect the future of the Ponca people?

MH: I see genocide. I see my people dying every day. I have children, I have grandchildren. I think that if we stay here, we’ll die. How many children and how many of my grandchildren are going to develop cancer? I’ve thought about leaving to make a new life somewhere else many times, but what kind of person would I be to leave my people behind to just go and worry about myself? Out of 30 wells around the reservation, every single one is leaking methane gas. It just blows my mind to see how much methane is leaking into the air, and how close some of these wells are to homes and to the community. There are no fences around the wells, no warning signs saying “stay out of this area,” “don’t smoke,” or anything like that. A lot of kids think that that’s a good place to go and have their parties. It’s just a serious danger and a health threat and a major contributor to climate change. The future depends on the decisions we make now. We need to be looking at renewable energy and putting people, instead of profit, first. If we choose to keep using fossil fuels and keep draining mother earth of her lifeblood, there will be serious repercussions. We’re having earthquakes here in Oklahoma now. It’s a scary thing knowing you live five miles from a refinery with hydrochloric acid and hydrogen sulfide, and if a big earthquake opens up one of those wells or breaks a pipeline, everything in 12 miles will be killed. That’s not only my community, but everybody in the community of Ponca City and the surrounding areas. We have to take care of mother earth.

All photos by David Hernández Palmar.