Harnessing the power of the sun is nothing new to many Indigenous communities. Solar energy has been used for thousands of years in many different ways for heating, cooking, and drying. Around the world, communities are again turning to solar energy to solve their rising needs for electricity as well as to affirm their Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. Through their participation in Makxtum Kgalhaw Chuchutsipi, Tutunakú youth are leading the way to defend their territories and build sustainable energy sources for their communities. Makxtum Kgalhaw Chuchutsipi is a Tutunakú organization made up of youth between the ages of 14-30 from 10 communities along the Ajajalpan River in the north of the State of Puebla, Mexico. The organization was created in 2013 when Grupo Mexico, a Mexican conglomerate that is the leading mining operator in Mexico and the third largest copper producer in the world, tried to claim lands in several local Indigenous communities. Their local environment is threatened by additional large-scale development projects including a hydroelectric dam project by Comexhidro, which will supply energy to Walmart.

A Keepers of the Earth Fund grant was awarded to Makxtum in 2019 to strengthen the voices and leadership of Tutunakú youth to defend their lands and water resources from unwanted mega-development projects. Tutunakú youth understand that energy is an important need for the communities and that alternative sources are possible; they know that hydropower is not their only option, in spite of what large scale production companies want them to believe. Recognizing their interest in renewable energy, Makxtum trained the youth in alternative energy production, including photovoltaic solar panels, as part of their strategy to achieve energy sovereignty. They also created videos about Tutunakú spirituality and their Peoples’ relationship with water.

In the training that Makxtum youth received related to land defense, they gathered information about the hydroelectric project and the possible impacts it would produce in their communities. Development companies and extractive industries see youth as a strategic group to engage, and many of these companies are targeting them to convince them to approve development projects in their communities, often by offering job opportunities. Makxtum carried out this project because they believe “it is necessary to work more with young people so that they learn how energy can be generated without harming Mother Earth, and so that they learn the negative impacts generated by megaprojects.”

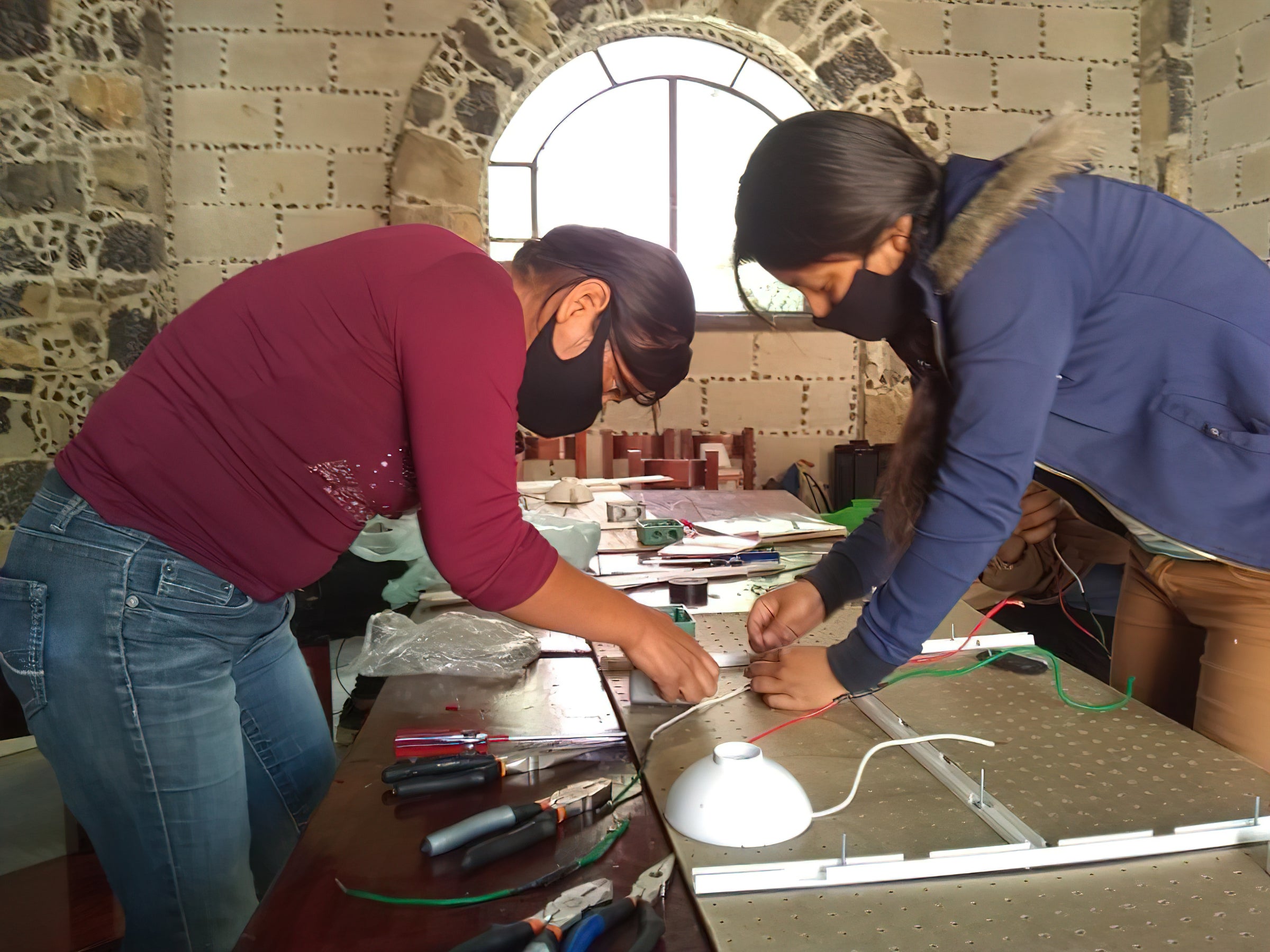

Instituto Mexicano para el Desarrollo Comunitario and Onergia are two organizations supporting the youth in this project. Twenty-seven youth participated in the trainings, which were paused several times in the past year due to the pandemic. The youths’ learning process included visits to other energy projects to learn about them firsthand. After one such visit to the Necaxa hydro plant, a participant said, “This visit helped us understand that not all hydroelectric plants generate clean energy and that large foreign companies do not care about the damage suffered by the population where the project is located. This motivated us to learn more about renewable energy and that not all renewable energy projects are suitable for the communities.” The youth also had the opportunity to travel to Cuetzalan, Puebla to visit Nahua Indigenous projects similar to theirs, an experience that helped them to see the possibilities of their own project.

“I was always interested in knowing how the energy worked and how it reached our homes. This course helped me a lot because I learned things that I did not know and saw how important energy is to our life. Renewable energy generated by solar panels helps protect Mother Earth from further damage. We still have more to learn. I am grateful for having this opportunity to participate,” said Griselda Luna, a participant from the Alticato community. “The idea is to continue learning and to be able to advance the training with other young people in other towns so that the learning does not remain only in us. We need to show others that we can generate energy without drying up rivers, without the painful need to pipe water and kill aquatic animals,” said José Galindo from San Felipe Tepatlán, about his experience.

Almost half of the participants were women; Makxtum had the firm intention to promote Indigenous women’s leadership in their trainings, and as such, adapted the workshops so more young women could participate. Members of Makxtum had direct conversations with families and reached agreements about their daughters’ participation, reduced the time for each training, and made sure the young women were accompanied to make them feel safe. Makxtum training projects have been a great experience for the youth. They want to continue their work, and more youth and families want to send their children to learn about alternative energy. The youth of Makxtum continue to work against the energy “projects for the dead,’’ (a term commonly used in Mexico as part of community campaigns against megaproject impacts), instead focusing on building alternative projects “for life.” Cultural Survival is honored to be able to contribute to their efforts.

Keepers of the Earth Fund (KOEF) is an Indigenous-led fund within Cultural Survival designed to support Indigenous Peoples’ community development and advocacy projects. Since 2017, through small grants and technical assistance, KOEF has supported 119 projects in 31 countries totaling $488,475. KOEF provides, on average, $5,000 grants to grassroots Indigenousled communities, organizations, and traditional governments to support their self-determined development projects based on their Indigenous values. Predicated on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Cultural Survival uses a rights-based approach in our grantmaking strategies to support grassroots Indigenous solutions through the equitable distribution of resources to Indigenous communities.