One week before this CSQ was sent to the printers, armed guerrillas, the Zapatista National Liberation Army, marched into San Cristobal de Las Casas, in Mexico's state of Chiapas. Here, and in several other towns, the violence drew world-wide attention to an area characterized by endemic inquality and conflict overland, resources, and labor since the early 16th century.

As the fighting continues, Mexican Scholar Jorge G. Castañeda wrote in the Boston Globe:

"Before all the facts are available, assorted explanations, most of them wrong, will be offered for the appearance of Mexico's first guerrilla movement since the 1970s. The Chiapas indigenous peasant uprising will be blamed on Guatemalans, priests, Cuahtmoc Cardenas, the CIA, poverty ethnic resentment and whatnot. It will be explained away as short-lived, localized, eccentric and exceptional. Some of the motivations will make sense-poverty, discrimination against indigenous peoples-but have been true for centuries without provoking an armed explosion. The others will simply be self-serving, seeking to dodge the hard question that Mexico must answer: How is it that a nation theoretically propelled into the First World by NAFTA, free-market technocrats and English-speaking yuppies has suddenly been rocked by Indians-Tzeltzals, Tzotozils, Tojolavas, Cholsfighting a modern army with machetes and sticks and stones as well as automatic weapons?

"The answer, of course, lies not in the motivations and origins of the Chiapas revolt but in the mistaken nature of the original assessment: Mexico has not been, nor will it be anytime soon, the modern, lily-while, middle-class and democratic society its rulers and their friends in Washington want it desperately to be. Or, more correctly, Mexico is at least two nation: the one present at the NAFTA coming-out parties in Washington and the one that reared its head in San Cristobal de las Casas on New Year's Day. To confuse one for the other is a major mistake; to believe that the first Mexico is more relevant to the future than the second one is understandable but equally wrong."

Castañeda goes on to note:

"This is not, strictly speaking, an armed peasant `jacquerie,' but a well-organized, partly well-armed guerrilla movement. It has at least a thousand recruits, some of whom are uniformed and carry modern weapons, some who do not. It has a centralized command, substantial communications and logistics capability, a coherent (if archaic) political philosophy and a sophisticated sense of public relations. It is doubtful that it can stand up to the Mexican army for long or hold any towns or territory, but it is certainly not a spontaneous, outraged `Indian revolt.'

"It remains a mystery how a thousand peasants could organize, train and equip themselves, plan and coordinate such a major military operation without the Mexican government doing anything about it. It's not as if the so-called Zapatistas were a secret. As recently as last August the weekly Proceso ran a long story on the guerrilla movement; earlier the daily La Jornada had reported on the first skirmishes in the town of Ocosingo. The Mexican security machinery, corrupt and brutal as it may be, has a well deserved reputation for efficiency. Why was nothing done to forestall the inevitable and predictable guerrilla offensive? Was the omission deliberate, and if so, who should be blamed for the hundreds of lives now lost?

"The crisis in Chiapas is not by any means exclusively economic. The southern state is one of Mexico's poorest, and the discrimination against its destitute indigenous peoples is dramatic, but these facts alone do not account for what happened. Indeed, Chiapas was something of a showcase for President Carlos Salinas de Gorteri's much-touted Solidarity anti-poverty program: More money form the Salinas government and the World Bank was funneled into Chiapas than any other state. The problem is that the authoritarian, untouched-or even were strengthened. The local authorities and the army and the police beat up, harassed and intimidated the indigenous landholders."

As news stories and new interpretations continue to flow out of San Cristobal-many of them as good as Casteñeda's - it is too early to identify the sources of the conflict or to trace we can begin to question these analyses. For example, after detailed interviews with local non-Indian - ranging from the Church to the military - and a series of quotes from a few articulate members of the guerrilla movement, we may be told, for example, that we have witnessed some form of revolution of rising witnessed some form of revolution of rising expectations sparked by NAFTA. Maybe it's true, but the interpretation still lacks a critical, broad-based indigenous voice.

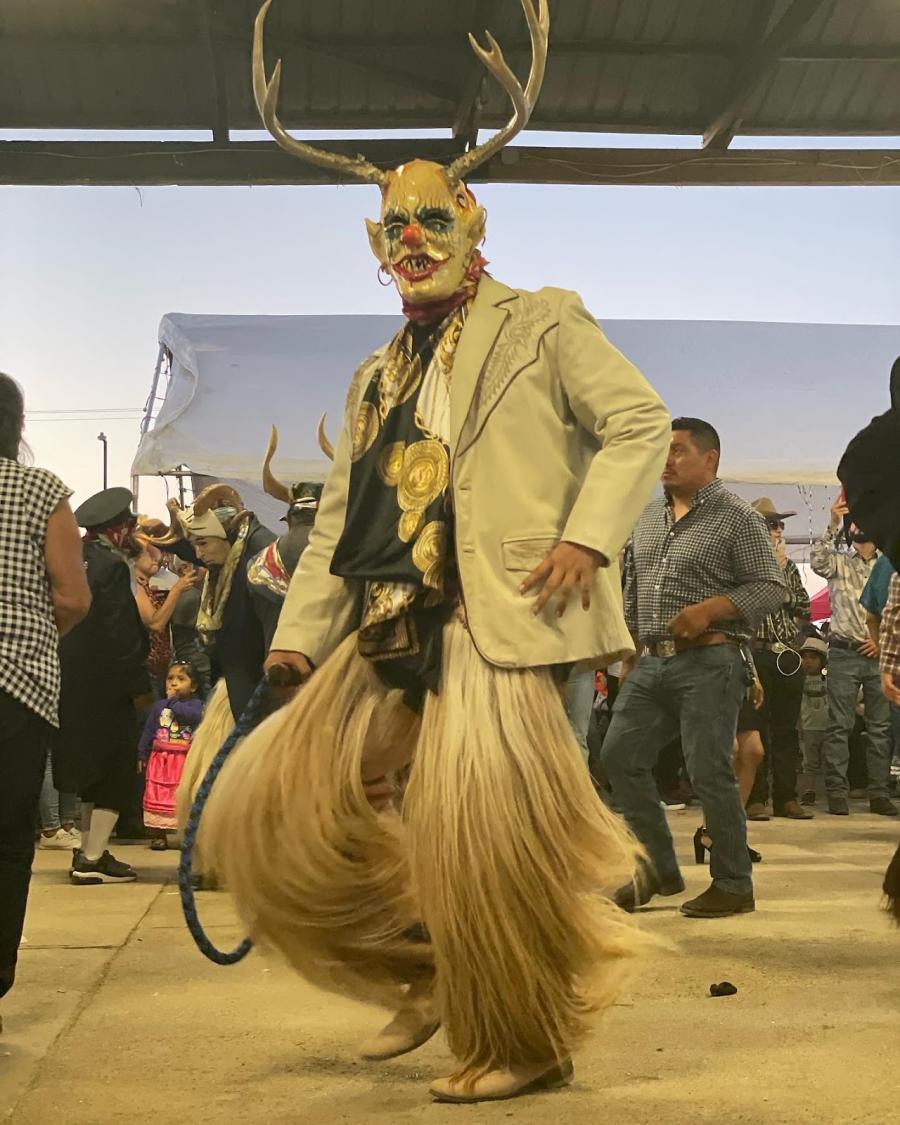

For over 500 years the Mayan Indians of Chiapas have displayed their understanding of post-conquest history and current events through elaborate tales and rituals of protest and profanation. The messages are consistent and illustrate a clear understanding of self and situation - angry and marginal. As yet there is no Tzotzil Times or "Indio" Country Today in Chiapas, but that is probably a matter of time. As the Cold War's cape no longer cloaks the analysis of ethnic unrest, we must learn how to listen for such voices, and to respond to them. Otherwise we may assume that, for the residents of hundreds of small hamlets, a loan from the World Bank somehow offsets a visit by the army.

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.