The path to achieving political autonomy in local government has been very complicated for Indigenous Peoples in Mexico. Many barriers have been placed in the way of exercising their rights. Political and social violence, long processes for those who seek recognition from the State, and the invisibility of those who already exercise autonomy under the shadow of State power, are just some of the problems faced. The national recognition of the historical, so-called “Indigenous normative systems” and others that are emerging in various states, has yet to be realized.

Many Indigenous communities have maintained their forms of community organization rooted in resistance against the pressures from the State. This almost always includes a collective and rotating form of governance, as well as the administration and collective ownership of land. In these communities, family representatives make up the community assembly, the most important body of power in the community. In assembly meetings, key decisions are made for the community, such as the election of government representatives, approval of the use of the community budget, the performance of community works, and the appointment of authorities. The positions are considered service and have a relatively short duration, generally between one to three years.

Although several communities in Mexico have managed to maintain this collective form of governance, many times they live in the shadows; at the local level they maintain their collective forms of governance, but they must also participate in the political party system, which implies accepting the installation of polling stations and political propaganda in their communities and voting in municipal, state, and federal elections. Participating in a political party system has kept communities in constant political and social crisis due to power disputes between those parties. In many cases, chiefdoms and political monopolies have been established in the communities.

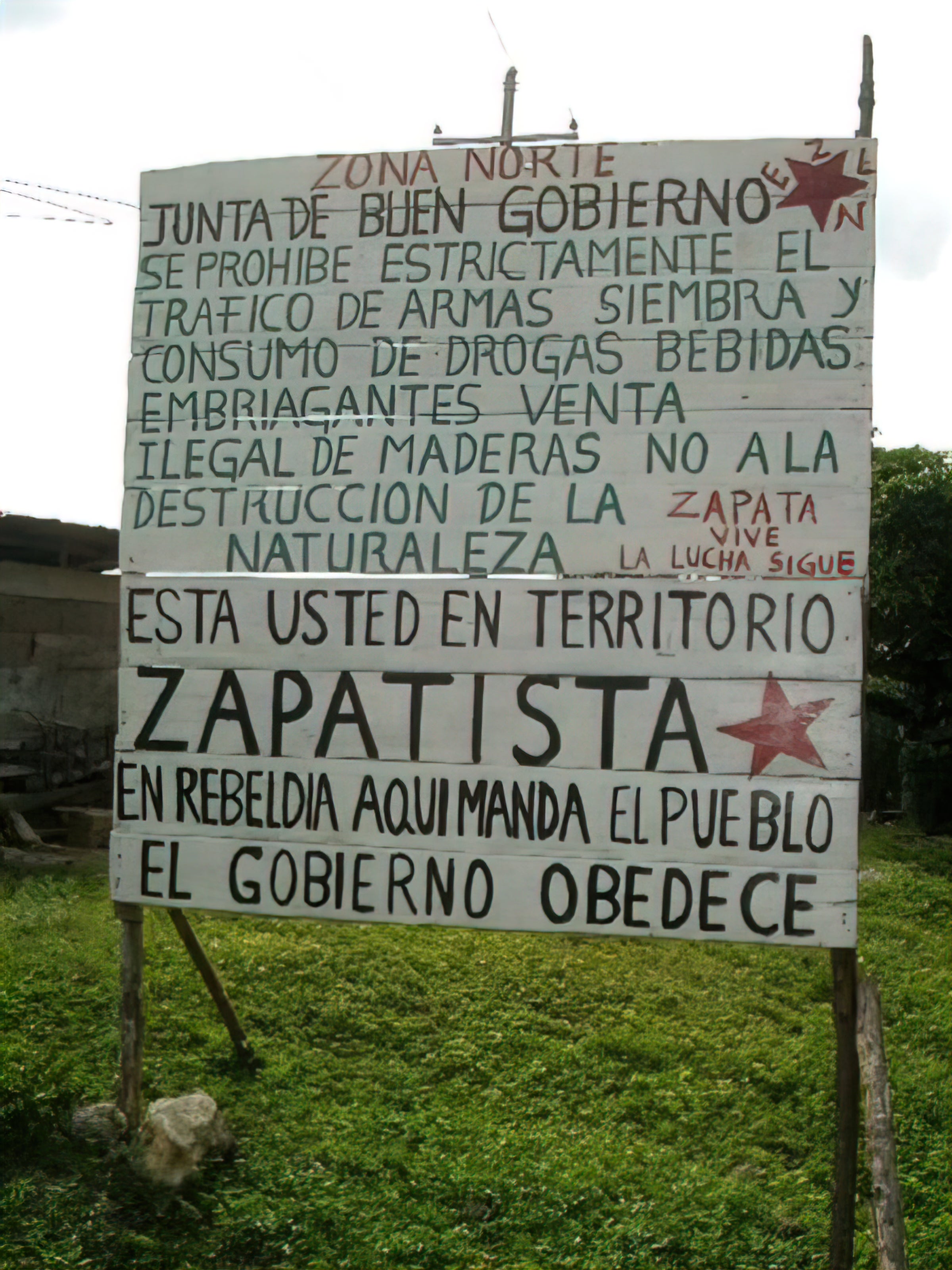

Zapatista communities in Mexico have maintained their ancestral forms of government and have been living in resistance against pressures from the Mexican State since 1994.

According to activist Yasnaya Aguilar (Ayuujk), “modern States have generally shown great resistance to recognizing the autonomy and the right to self-determination of Indigenous Peoples. The Mexican State in particular has preferred to confine the Indigenous Nations in cultural categories and not in political categories. Despite the fact that the Mexican Constitution grants them autonomy, it was only in 1995 that the local legislature—only in the state of Oaxaca—recognized these practices [of governance].” This constitutional achievement was partially the result of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, a movement made up of Tzotzil, Tzeltal, Tojolabal, Zoque, and Ch’ol Mayan Peoples. This movement was a watershed in the right to self-organization and the struggle for self-determination of Indigenous Peoples in Mexico. In 1994, in an exercise of autonomy, the organization of 29 communities decided to remain independent from the State rather than become a recognized political entity.

In other more recent cases, there have been multiple threats to Indigenous communities, such as concessions granted on their territories for extractive megaprojects without due consultation. Supported by the dominant democratic system and in clear violation of Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination, several communities have been moved to analyze their political organization and have decided to decolonize their forms of governance, thus moving from a system of political parties to a collective form of power and governance.

“You are in Zapatista territory in rebellion, here the people rule and the government obeys.” Sign on a road in the Altos de Chiapas area. Photo by gaelx.

In the south of Mexico in 2015, the Tzeltal Peoples from the municipalities of Chilón and Sitalá in Chiapas began their process of autonomy with the main objective of building what they call lekil cuxlejal (community harmony), which includes working with the land, conflict resolution, and community communication, in addition to the appointment of positions. However, the transition to Indigenous self-government has been difficult. In 2018, the communities reported intimidation, harassment, threats, and attacks against their members and the communities that form their social base. In 2020, two colleagues were arrested and imprisoned, “but with our ways of governance we managed to get them out, although they are still undergoing a [legal] process,” one of the councilors told Avispa Midia magazine.

Despite the fact that in 2019 the legal process began in the Institute of Elections and Citizen Participation for the transition to an internal regulatory system, no IEPC officials have been able to go to Indigenous territory, Pascuala Vázquez, the community government spokesperson, says, noting that COVID-19 has been used as a pretext: the pandemic did not stop the electoral campaigns, but has completely halted the legal process. Still, the communities persevered, and in May 2021 the assembly of the communities met to elect the Councilors of the Community Government in a full exercise of their autonomy.

Decolonization of the power structure is happening elsewhere in Mexico. The State of Guerrero has been plagued by constant violence for decades. As Pablo Ferri states in his article in El Pais, “many residents easily remember the El Charco massacre, an army counterinsurgency operation that killed 11 people in 1998; or the rape and torture committed by the military against a neighbor, Inés Fernández, in 2002; or the harassment by the state government against the first self defense groups in 2013 and 2014, which led some of their members to jail for years.”

In 2018, thousands of Na savi, Me’phaa, mestizos, and Afro-Mexicans decided in assembly to exercise their right to autonomy and reject the political party system by establishing an Indigenous Electoral Normative System. Of the 265 people elected to represent their communities, half were women and half men. The effort to get the communities to agree to change the way they had been governed took months, even years. “This exercise of Indigenous democracy was legitimately pushed by people who welcome the search and development of forms of government that call for inclusion,” journalist Sergio Ferrer wrote in La Jornada Guerrero.

In 2011 in the State of Michoacán, the P’urhépecha women of the Cherán K’eri municipality called on the population to defend their territory, closed access to the community, and established permanent camps where they gathered to exercise their political autonomy. In a collective and organized way, they established an autonomous government endorsed by the Electoral Tribunal of the Federal Judicial Branch, with which they managed to expel organized crime that had been illegally exploiting their forests for several years and creating a climate of insecurity and violence in the area.

Cherán’s 10-year path of resistance has been complex, but it has served as an example for other communities in the same region and in other parts of the country. In 2021, several communities decided to go further and not participate in the political system at higher levels, successfully resisting the installation of 92 polling places from the previous election for local deputies and state governor. This was done by 23 P’urhépecha communities, plus 10 Mazahua and Otomi communities from the eastern region of Michoacán.

Other communities have taken steps toward collective autonomy within the same framework of the political party system. Ahuehuetitla is one of the most impoverished municipalities in the Mixteca region in Puebla and has a rate of high migration. In the last elections, some 372 voters from more than 2,000 citizens decided not to choose any of the seven candidate options offered by the political parties. Instead, they elected Adán Seth Calixto Guerra, who won by majority even after 70 votes were annulled. Calixto Guerra did not register as a candidate for any political party or as an independent candidate, which means that he did not have a budget allocated for an electoral campaign. Now he faces a legal battle to recognize his victory.

All political autonomies, whether historically recognized (as in the State of Oaxaca), newly recognized (such as Cherán and Ayutla de los Libres), or those who have chosen to forego the recognition of the State altogether (like the Zapatista Autonomous Communities), have faced attacks by the State in their fight for and respect of self-determination. In their perseverance, they are paving the way for other communities, who, with slow but sure steps, are reclaiming collective forms of government as a way to defend their Indigenous territories and lifeways.

Top Photo: Zapatista radio stations were established in 2009 as part of a larger autonomy process to denounce social injustices in their communities. Photo courtesy of Zapatista Radios.