On New Year's Day, 1994, the citizens of Mexico expected to wake up to a celebration of Mexico's entry into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Instead, they woke up to an armed rebellion in the State of Chiapas.

The Zapatista National Liberation Army took its name from Emiliano Zapata, a hero of the 1910-1917 Mexican Revolution, who fought for "Land and Liberty." When the Zapatistas seized the public squares of the major towns of eastern Chiapas, they carried the symbolic banner of an ecological revolution. For despite its religious and ethnic overlays, the Zapatista revolt was essentially an ecological struggle, one that focused on two central questions: Who controls the land, and what do they use it for?

Since at least the Colonial era, Chiapas has been a source of extracted products that have gone to benefit other regions of Mexico. The state has 30 per cent of the republic's surface water, and its dams supply between one-third and one-half of the country's hydroelectric power. Nonetheless, Chiapas ranks last among Mexican states in households with electricity (Golden 1994). Chiapas also has much of Mexico's petroleum reserves, not all of it yet in production. The state has one of the highest percentages of forest cover of all states in Mexico, although most of its commercial hardwoods have already been extracted and sold. At the same time, Chiapas has the highest rate of deforestation in Mexico, largely due to clearing forest land for two or three years of corn and bean (milpa) agriculture, then converting it to pasture for beef cattle.

The state's deforestation rate has been exacerbated by a rapid increase in the number of rural families. The rate of natural increase in Chiapas has been 3.4 per cent per year during the past 20 years. In the Lacandon Forest (Selva Lacandona) of eastern Chiapas, this rate combines with immigration to reach seven per cent per year, a growth rate that will double the population within 10 years. According to 1993 World Bank statistics, 52 per cent of the population of the Selva Lacandona is under 15 years of age (World Bank 1994).

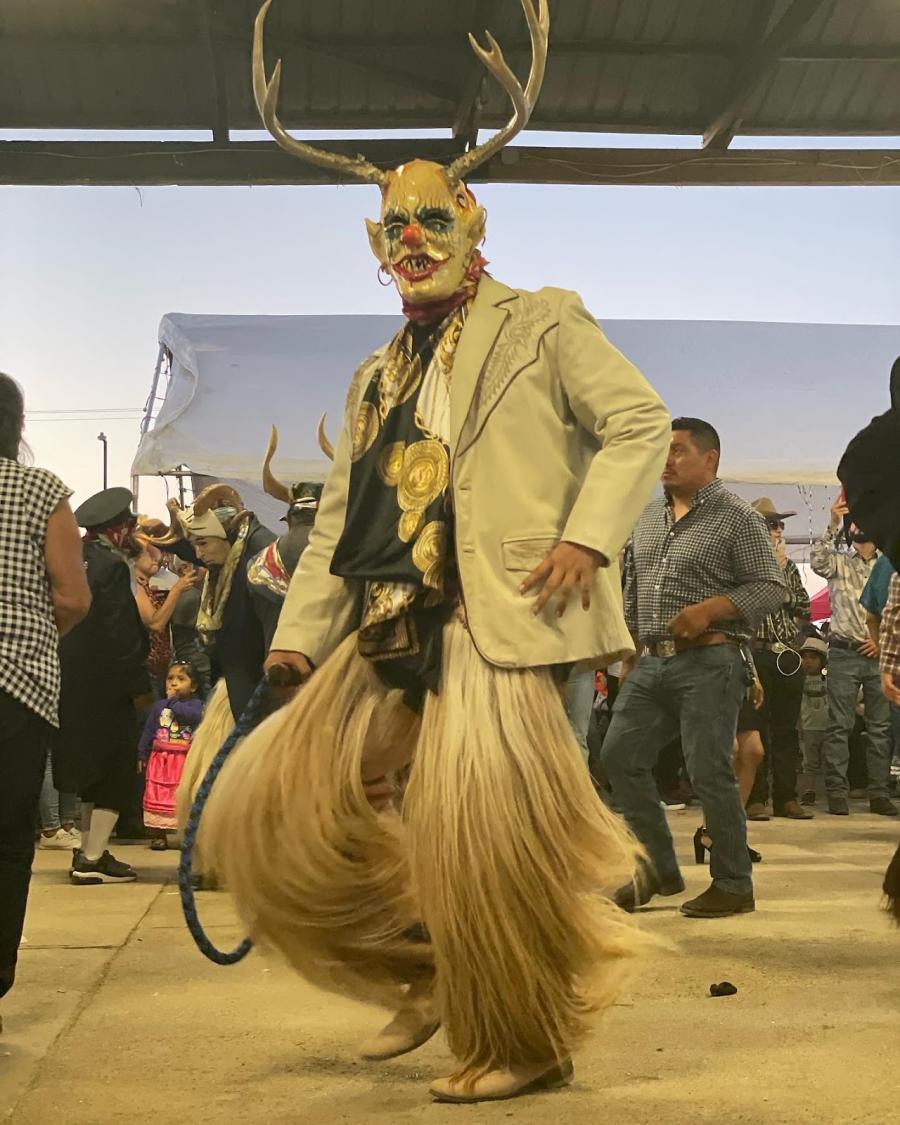

The Zapatista revolt took place in a region of Chiapas characterized by three ecological zones. In the center of the state rise the Chiapas highlands, covered by an open forest of pine and oak. Since pre-Columbian times, the highlands have been the home of the Tzotzil Maya, whose colorful huipiles and syncretic Maya-Christian religion draw tourists to the towns of Chamula and Zincantán. A combination of dense population and Colonial history has relegated much of the Tzotzils' highland forest to regrowth. Little original forest remains. During the 300 years of Colonial domination, the Tzotzil Maya highlands were converted to wheat, corn, and sheep production for the benefit of Spanish landlords. Through Colonial systems of royal land grants (encomienda) and grants of indigenous labor (repartimiento), the Spaniards came to own both the land and the labor of its indigenous occupants.

East of the highlands, the mountains fade into foothills covered by a transition forest in which pine and oak trees give way to species of lowland tropical forest. Ethnohistorical accounts indicate that these foothills, and their market towns in the Ocosingo Valley, have been the home of the Tzeltal Maya for at least 1,000 years (de Vos 1980). Here, most of the forest was cleared during the Colonial period to produce sugarcane and cattle for Spanish landlords. In the southern reaches of these foothills, the Tojolbal Maya long produced cattle and sugar for Spanish landlords, later turning to coffee as a cash crop and corn and beans for subsistence (Wasserstrom 1983).

The eastern edge of these foothills, called "Las Cañadas" in Spanish, centers on the towns of Ocosingo and Las Margaritas. This is the homeland of the Zapatista Army, as well as the site of much of the fighting that jarred Mexico in early January, 1994. The vast majority of Zapatistas are Tzeltal and Tojolabal Maya, with a sprinkling of Ladino auxiliaries.

The third ecological zone of eastern Chiapas is the Selva Lacandona, a lowland tropical forest that shelters jaguars, tapirs, monkeys, and macaws. Until the 20th century, the selva covered 13,000 square kilometers, stretching eastward from Ocosingo and Las Margaritas to the Usumacinta River. Today, two-thirds of this forest has been cleared and burned for milpas and pastureland, leaving only the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve (3,140 km2) in its original vegetation.

When Spaniards invaded Chiapas in the early 16th century, they found the highlands occupied by Tzotzil Maya, the foothills by Tzeltales and Tojolabales, and the Selva Lacandona by Chol and Cholti Maya. At that time, the people we call the Lacandon Maya occupied the tropical forest area of what is now the Department of Peten in Guatemala.

Under Colonial rule, the Chol and Cholti Maya fared even worse than the Tzotzil and Tzeltal. During a series of military and missionary expeditions of the 16th and 17th centuries, the Chol and Cholti of the lowland tropical forest were either killed or relocated into the northern foothills (near today's towns of Bachajon and Yajalon) to work on Spanish haciendas. Their elimination from the Selva Lacandona created a population vacuum that was gradually filled during the 18th and 19th centuries by Yucatec-speaking Maya fleeing disease and disruption in the Guatemalan Peten. The Spaniards called these immigrants "Lacandones," a name they had previously applied to the Cholti (de Vso 1980).

The transformation of Chiapas from Spanish colony to Mexican state had minimal impact on the ecology of the region. The Mexican Revolution of the early 1900s did little to affect the area's dramatically skewed land ownership. During the 1950s and 1960s, however, the agrarian reform laws of the Mexican constitution gradually came to be applied in Chiapas, and thousands of Maya families were released from debt peonage on Ladino haciendas in the Chiapas foothills. Urged on by state and federal officials, these families migrated eastward into the valleys of the Selva Lacandona to create new communities on what were considered to be vacant forest lands.

This influx of indigenous immigrants turned into a steady flow after two U.S.-based timber enterprises sold their unworked timber rights to a group of Mexican businessmen during the mid-1960s. The businessmen began to bulldoze roads through the Lacandon rainforest to take out mahogany and tropical cedar trees that earlier, river-based logging teams had failed to reach.

As trucks carried mahogany and cedar out of the forest on these new roads, landless Tzeltal, Tojolobal, and Chol Maya families flowed into the forest seeking new land and new lives. Within a decade, these colonists were followed by a second wave of settlers - this time cattle ranchers from the Mexican states of Tabasco and Veracruz. These ranchers began to buy up the pioneer settlers' cleared plots and turn them into large cattle enterprises. The farmers pushed farther into the forest to clear more land.

As immigrant Maya farmers and Ladino cattlemen set about clearing the Selva Lacandona, they unwittingly fulfilled a national strategy created by politicians in Mexico City, a policy that divided the republic into two units of economic production. The northern states of Mexico were - and continue to be - used to produce beef cattle for export to the United States. The tropical lowlands of Veracruz, Tabasco, and Chiapas became the source of beef and corn for consumption in Mexican cities (Gonzales Pacheco 1983).

Profits from timber operations in the Selva Lacandona also fit into this plan, producing flushes of capital for state - and privately-owned companies. But by 1971, the individuals who controlled these companies realized that the farm families they had pushed into the Selva Lacandona were clearing and burning the forest before the commercial hardwoods could be extracted. In reaction, in 1971, the Mexican government decreed an indigenous reserve of 641,000 hectares and declared 66 Yucatec-speaking Lacandon Maya the sole owners of the area. Simultaneously, they signed timber rights agreements with these families and set about extracting the reserve's remaining mahogany and cedar trees.

The Lacandon land decree was met with protests from the Tzeltal and Chol Maya who had already colonized the territory of the new Lacandon Reserve, for their families had been transformed overnight into illegal squatters on Lacandon land. In reaction, Mexican officials recognized the land rights of 5,000 Tzeltal maya and 3,000 Chol Maya who lived in the Lacandon Reserve. But in a move reminiscent of the 16th century Spanish reducciones, which concentrated scattered indigenous populations into Colonial towns, the Mexican government required the Tzeltales to relocate into the community of Palestina, renamed Nuevo Centro de Población Velasco Suárez, after the Chiapas State governor at the time. The Chol Maya were relocated into the settlement of Corozal, renamed Nuevo Centro de Población Echeverría, after Mexico's president. The two centers became the largest settlements in the Selva Lacandona.

Thus, the Lacandon Community (Comunidad Lacandona) came to include three indigenous groups: the Tzeltal Maya of Palestina/Velasco Suárez, the Chol Maya of Corozal/Echeverría, and the Lacandon Maya of the communities of Lacanja Chan Sayab, Mensabak, and Naja. This issue continues to confuse the press, and sometimes Chiapanecos, who are hard pressed to distinguish between the 400 members of the Lacandon Maya and the 8,400 members of the tri-ethnic Lacandon Community.

The Zapatistas only added to the confusion in their initial press statements declaring that they were fighting to secure land and freedom for the inhabitants of the Selva Lacandona. But the three elected representatives of the Comumidad Lacandona - one each from the Tzeltal, Chol, and Lacandon Maya settlements - immediately issued a public letter denying involvement in the revolt and expressing support for the Mexican federal government.

Outside of the Comunidad Lacandona, colonization and deforestation have continued. In 1973, the government-owned Nacional Financiera, S.A. (NAFINSA) purchased the Mexican-owned lumber companies operating in the Selva Lacandona and expanded the number of roads cutting through the region. Five years later, this network of forest roads took a quantum leap when the Mexican national oil company, PEMEX, declared the Selva Lacandona one of the nation's richest oil fields and began exploring 2,500 square kilometers of forest.

As in the eastern foothills, the farmers who used these roads to colonize the forest surrounding the Comunidad Lacandona established communal farms (ejidos) to produce corn and cattle. But the rapid establishment of dozens of new ejidos led to land disputes with existing communities, cattlemen, and the Comunidad Lacandona itself. These disputes expanded as agricultural land was converted to pasture, forcing a constant need for additional forest land to grow food crops.

As recently as 1981, the Mexican press was reporting that the Selva Lacandona was being sacrificed to fee the nation's growing population and to achieve self-sufficiency in basic grains. But in fact a 1981 study by a Mexican anthropologist indicated that - although one-third of the Selva Lacandona had been destroyed - 80 per cent of the cleared area was dedicated to cattle pasture (Lobato 1981). In reaction to national and international concern over this deforestation, the Mexican government established the 3,310 km2 Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, 85 per cent of which overlays the forest territory of the Lacandon Community.

Rather than viewing this overlap of protected area and indigenous territory as a threat, the Tzeltal, Chol, and Lacandon Maya of the Comunidad Lacandona see the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve as a buffer against outside threats to their land. Their persistent requests that the area's tropical forest be protected have become more frequent in the face of the Zapatista Army's demands for additional land. Lacandon spokesmen have stated that the Comunidad would prefer to see any new agricultural lands come from the landholdings of ranchers in the Ocosingo Valley, rather than from the remaining forest of the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve. Fortunately, the public statements of the Zapatistas seem to coincide with this stance, for the Zapatistas have declared respect for natural resources as part of their goal.

However, other farmers in the Selva Lacadona appear to have taken advantage of political unrest in the region to seize lands of the Comunidad Lacandona. Tzeltal farmers have already burned 100 hectares of forest belonging to the Lacandon Maya of Naja, and the Lacandones of Mensabak report rumors of planned invasions of their legal territory. In the words of one Lacandon Maya leader, "They have turned all their forest to pasture, and now they want the forest we have kept alive for our families."

A satellite view of eastern Chiapas reveals that the majority of the Selva Lacandona and the foothills of Chiapas are now occupied by farmland and pasture. In the past 34 years, the population of the Selva Lacandona has skyrocketed from 6,000 inhabitants to 300,000 (World Bank 1994). It is not surprising that pressure for land reform and disputes over land title have increased in both the lowland forest and foothill regions. Today, 30 per cent of unresolved land disputes in the Republic of Mexico occur in Chiapas.

Recent national and international events have not aided this flashpoint situation. In 1989, Mexico dismantled its coffee price control system, feeling coffee prices were secure. But almost simultaneously, world coffee prices fell, throwing thousands of small-scale coffee producers in the Selva and foothills into bankruptcy.

Only a few years later, in 1992, the Mexican government altered Article 27 of the mexican constitution, allowing communal farmers (ejidatarios) to sell their communal land for the first time in history. The goals of the Salinas administration were clear: more productive agriculture through more efficient production on larger land holdings.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) complicated the situation by altering tariffs on corn imports. Mexico already imports some corn from the United States, but under NAFTA this amount will undoubtedly increase. NAFTA establishes a yearly, duty-free import quota of 2.5 million metric tons, with tariffs on amounts over that, and a total linear phase-out of tariffs over 15 years (Hufbauer and Schott 1993:47-57). In the words of the Zapatistas' Sub-Comandante Marcos, "NAFTA is the death certificate for the indigenous people of Mexico."

Little wonder that some Chipaas farmers began to feel they were victims of a conspiracy in which they soon would be without a market for their crops and no land to grow them on anyway.

In the midst of this, the cattlemen continue to patrol the fences of their sizeable holdings, and the population of Chiapas continues to grow. It is not difficult to imagine a Tzeltal or Tojolbal farmer sizing up his situation into three choices: he can move to San Cristóbal de las Casas and sell popsicles from a pushcard, he can work for a cattleman punching cows, or he can rebel against a situation that seems to have him trapped. That hundreds of farmers chose to rebel should come as no surprise.

It would be fruitless to argue for the preservation of all the forests of eastern Chiapas. Most of those forests are already gone. But it makes sense, for the benefit of the indigenous inhabitants of the Selva Lacandona and for the people of Mexico, to keep alive what little forest remains. President Carlos Salinas de Gortari had exactly this goal in mind when he expanded the protected areas of the Selva Lacandona by 81,000 hectares in May, 1992.

The challenge remains to transform the rest of eastern Chiapas into an ecologically sustainable mosaic of food production, agroforestry, small-scale cattle production, and extractive forest reserves. To do so would be positive for the region's natural ecosystems and positive for the region's inhabitants - indigenous and Ladino alike.

It is clear that the government of Mexico must work with the indigenous communities of the Zapatista foothills to create additional income and employment. But to provide these necessities by increasing the amount of land under cultivation will be possible only by taking land from the cattlemen to the west or from the forests of the Comunidad Lacandona to the east.

It is also certain that the Mexican government, and perhaps international agencies as well, will be tempted to flood eastern Chiapas with funding to quiet indigenous demands. The World Bank is already holding $10 million dollars for Chiapas, and part of the $30 million of Mexico's Global Environmental Facility (GEF) funding is aimed at the Selva Lacandona. Concerned citizens in Mexico, and elsewhere, would be wise to assure that these funds are applied in ways that make economic, cultural, and ecological sense. Not to do so is to invite further unrest in this ecologically and ethnically sensitive region of Chiapas.

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.