Today the remarkable work being done by Native people to reclaim lands and revitalize languages, cultural traditions, and governance structures is a testament to the resilience and strength of Native peoples in the United States. The history of Native people in New England has been one of annihilation, displacement, and cultural dispossession. This issue of Cultural Survival Quarterly focuses on the thriving, changing, and adapting contemporary cultures and traditions of New England tribes as told by members of the tribes themselves.

The tribes and bands of New England have deep histories of early contact with European settlers and colonizers, and today have a political status that distinguishes them from the majority of more than 500 federally recognized American Indian tribes in the United States by virtue of holding unique jurisdictional relationships with states. Although federal settlement legislation contains language supporting the sovereignty of the tribes, New England states with narrow interpretations of federal statutes make it difficult for tribal governments to serve and protect their peoples, lands, and cultures. It is a constant source of conflict, as we see with the Pequot and Passamaquody tribes.

The many tribes in the New England region—the Abenaki, Eastern Pequot, Golden Hill Paugussett, Haudenosaunee (Mohawk, Oneida , Cayuga, Tuscarora, Seneca), Maliseet, Mashantucket Pequot, Micmac, Mohegan, Narragansett, Massachusett, Nipmuc, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Schaghticoke, Shinnecock, Unkechaug, Wampanoag (Aquinnah, Assonet, Chappaquiddick, Herring Pond, Mashpee, Seaconke, Pocasset), and several other bands—are working to reclaim their lands, languages, and cultures through rebuilding efforts. The Wampanoag School on Cape Cod is an example of an extraordinary effort in language reclamation and revitalization that is also reclaiming and promoting tribal culture and traditions, passing them on to the next generation through cultural-based education. As Jennifer Weston writes in her article, “As recently as 1993, there were no native speakers; Wampanoag children on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard grew up with little knowledge of their mother tongue.” Today, intensive summer language programs teach the language and cultural practices and ways of knowing. The spaces provided for artistic expression and creativity, such as the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, serve to revitalize culture. As Amy Ferguson and Sara Schenkel write, “The notion of spirituality within art is a common theme for Native artists as well as contemporary artists...art is not separate from culture: they are one in the same.”

Yet, full recognition of tribal rights and the rights of self-determination remains a challenge. As Penobscot Nation’s staff attorney Mark Chevaree states, “We’re advocating for the government to recognize our rights, just like other citizens do when they feel like their right of free speech, or their right to bear arms...when they’re advocating for those rights, that’s what the tribes are doing. We’re advocating for rights that are recognized by the US government. It’s not special privileges. It’s really about who gets to make decisions about governance, about how we choose our leaders to form our government, how we utilize our land, how we develop regulatory systems and law enforcement within our communities, who decides the rules around the taking of fish and wildlife.”

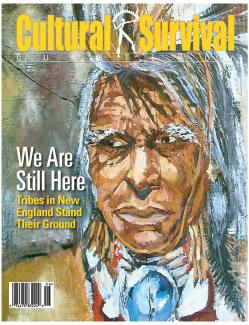

Activist artist Deborah Spears Moorehead’s painting, “Slow Turtle,” is a fitting statement to say “We Are Still Here:” as culturally and spiritually vibrant peoples as we always have been.

Suzanne Benally, Executive Director (Navajo and Santa Clara Tewa)