Dr. Dalee Sambo Dorough (Iñupiat) is the International Chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council. Carolina Behe is the Indigenous Knowledge and Science Advisor for the Inuit Circumpolar Council Alaska. Cultural Survival Indigenous Rights Radio Producer, Shaldon Ferris (KhoiSan), recently spoke with Behe and Dorough.

Cultural Survival: How do you define food security? What are the threats and challenges to maintaining it among Inuit communities?

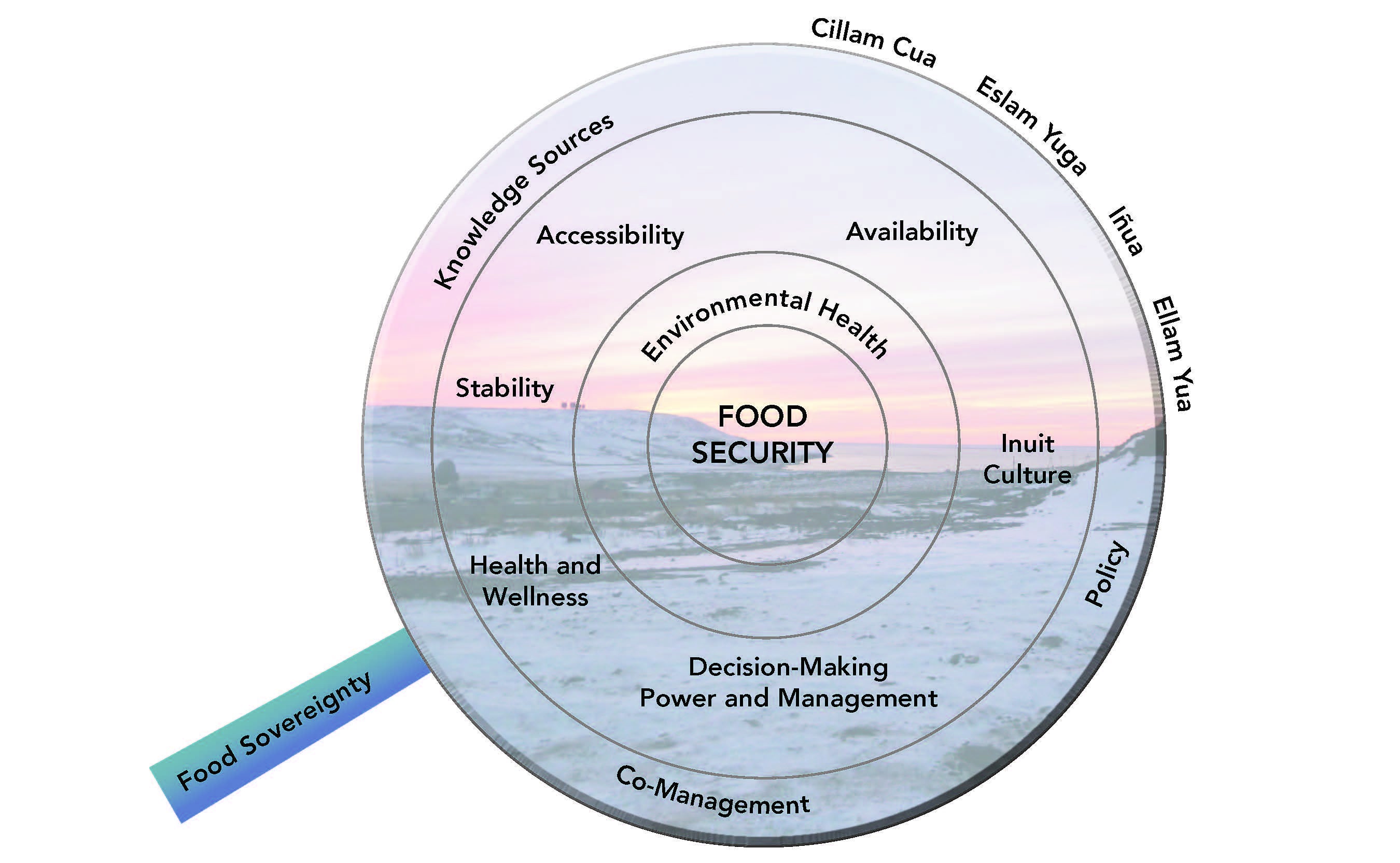

Carolina Behe: Quite a few years ago, Inuit in Alaska defined food security themselves. In that definition, it’s really clear that food security is characterized by a healthy environment and is made up of six different dimensions: accessibility, availability, stability, Inuit culture, health and wellness, and decision making power and management. Those six dimensions need tools to support them, and those tools are policies, knowledge sources (meaning both Indigenous knowledge and modern science), and true co-management. We visualize all of that in a drum. The handle of the drum is food sovereignty. Without food sovereignty, we cannot have food security. We have to understand the relationship between all of these pieces and that if even one piece is out of balance or not there, we will not have a healthy environment—we will not have food security.

Food Security Conceptual Framework (ICC AK 2016) from Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska. 2015. Alaskan Inuit Food Security Conceptual Framework: How to Assess the Arctic From an Inuit Perspective. Technical Report. Anchorage, AK.

Dalee Sambo Dorough: There are multiple threats to the food security of our communities, including climate change and pollution. These issues are compounded by the lack of understanding that the rest of the world, including our respective governments across the Arctic, have about the important and profound relationship that we have with the environment and all of the animals that we harvest, hunt, and fish. Inuit rely upon the marine environment; we are also one of the species within our Arctic environment. Our perspective of living in harmony, having a healthy relationship with the environment, is now facing multiple threats, making it difficult to briefly answer these questions because there are so many different things that are adversely impacting us and our food systems, our food security, and our food sovereignty.

CS: How is food sovereignty linked to self-governance?

DSD: Article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as Article 1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, first and foremost affirms the right of all Peoples to self-determination, which is recognized as a prerequisite for the exercise and enjoyment of all other rights. Included in Article 1 is a very important, sweeping sentence: “In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.” If you think about that in the context of Inuit food security, it’s directly and intimately linked with our right of self-government and our right of self-determination.

Self-determination, our role in policymaking and decision making, is directly tied to our food security. This is one of the significant conclusions of the work that the Inuit Circumpolar Council has done. Everything that we manifest in terms of our distinct cultural identity, our language, our customs, our practices, our food sources, our sense of intergenerational responsibilities—everything. It’s clear that there is a direct and intimate relationship.

CB: The very first sentence of the definition for food security that Inuit in Alaska developed says Alaska Inuit food security is the natural right of all Inuit to be part of the ecosystem, to access food, and caretake, protect, and respect all of life, land, water, and air. There’s a right to that responsibility. Inuit have been here for thousands of years, successfully being part of this environment and holding their relationships within that environment. There’s a real contrast between Inuit approaches and the way that the federal or state government approaches that relationship within the environment. Federal and state policy often center on control and siloed approaches, such as single species management. For Inuit, all of it is interconnected and values help shape the relationships held. For example, you don’t try to control the weather, you respond to it. All of this stresses the need to understand the interconnections—to understand that the health of the whale depends on the health of the hunter just as much as the health of the hunter depends on the health of the whale.

Processing seal meat. Photo by Jacki Cleveland.

CS: What supports or impedes Inuit food sovereignty?

CB: A large part goes back to Inuit management practices. Throughout Inuit homelands, people share food with each other. If there’s a place here in Alaska that is having trouble with being able to collect food one year, other Inuit communities around Alaska quickly share food with them. Within a community, people take care of each other. That’s something that strongly maintains food security. Values from Inuit management practices, like basing decisions on an understanding of cumulative impacts and respect for everything within that ecosystem, requires an understanding of connections across social, cultural, biological, and physical pieces of the world. There is a need for systemic change at the national international level, at international forums for the equitable engagement and inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in order to inform more holistic and adaptive decision making.

CS: What are some positive case studies of Indigenous food solutions?

DSD: One of the most important positive examples is that we’re still here; the fact that Inuit have the ingenuity to adapt to this environment where no other humans have been able to survive. As our founder, Eben Hopson, has stated, “Our language contains intricate knowledge of the ice that we’ve seen no others demonstrate.” We have been able to maintain ourselves out there on the land and on the coastal seas in a sustainable fashion, in a way that has allowed us to continue and to renew ourselves season after season after season. At the core of all of this is our knowledge, knowledge that has been accumulated over centuries and is still being accumulated by the individual hunters and through their relationships with others and also their sharing with others throughout the Inuit world. Indigenous knowledge has really become a record of our customs, our values, our practices, and our expressions of our relationships with the environment around us, which has generated the kind of food security that we seek to protect and that we seek to continue to have within our communities.

CS: What is the role of Inuit Peoples in managing Arctic marine resources?

DSD: As distinct Peoples reliant upon the ocean and coastal seas, we should be playing a central role in the management of the marine environment across the whole of the Arctic. In Alaska, the United States government’s treatment of the rights of Alaska Natives was misguided and misinformed. The result was the adoption of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. Implicit in that act was a promise that they would deal with what they refer to as Aboriginal hunting and fishing rights. In my view, to date, they have not dealt squarely with Aboriginal hunting and fishing rights or more specifically the harvesting rights of Inuit. In our particular case, they’ve chosen to work within a framework that is imposed by Westerners and not to embrace the distinct and inherent rights of Inuit in Alaska to be secure in their own means of subsistence.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act has been one of the biggest burdens that not only Alaskan Inuit have faced, but all Alaska Native people have faced by virtue of the imposition of the provisions of our so-called land claims agreement in 1971. We’re still dealing with this because the government has not explicitly affirmed our rights to hunting, fishing, and other harvesting activities. This fundamental challenge has to be overcome.

CB: In Alaska there is no true co-management. There are cooperative agreements. This differs from a co-management structure in which both groups are at the table to collectively make decisions together; to have both Indigenous knowledge and science equitably engaged; to have Indigenous values and management practices at the forefront. Within Alaska, the state and federal management practices are often single-species-oriented, which lacks a holistic understanding of how everything is interconnected. That creates quite a conflict. Even the fact that we refer to them as species becomes a way of objectifying the parts of the environment that people have relationships with. This siloed approach is further emphasized by the multiple agencies involved in managing different animals and habitats, managed under different mandates, and/or under different interpretations of the same laws.

CS: What does the future of Indigenous food sovereignty look like in the Arctic?

CB: In the food security conceptual framework, the drum, remember that all of the pieces are interconnected and needed. In Alaska, it was clear that what is really unstable is the lack of decision making power and management—and that directly links to food sovereignty. That is what led us to our current project. We’re doing a comparison within the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of Canada and Alaska to look at what impedes or supports Inuit food sovereignty. Within Alaska, it’s very clear that that lack of co-management, the lack of decision making power is at the height of it. Whether it’s climate change, conflict of interest, or the burden of conservation, all come back to decision making and looking at whose values are being put at the forefront when making those decisions within Inuit homelands. Within Alaska and internationally, it is often a dominant culture, economically driven, and people far from the Arctic making decisions and policy recommendations based on information and values that do not reflect Inuit, the Arctic, or a holistic understanding of the world.

The Food Sovereignty and Self-Governance report and resources on the food security framework can be accessed at iccalaska.org.

Top photo: Berry picking. Photo by Chris Arend.