Along with 250 other lowland Indians, Marta Gualinga trekked through the rainforest for there days before reaching Villano - the site of ARCO's exploratory wells. Lowland Quichua representing 133 indigenous communities throughout Ecuador's central Amazonian province of Pastaza gathered for an assembly called by OPIP (Organization of Indigenous Peoples of Pastaza). For three days in mid-December 1993, participants debated oil exploration and imminent production in Indian lands. Young men with starkly painted torsos and faces angrily denounced ARCO; more experienced leaders cautiously measured alternatives. Petroleum "development" had indelibly transformed the northern Ecuadorian Amazon where scant industrial restrictions over the past 25 years caused significant social and environmental degradation. As hydrocarbon operations moved south, OPIP-affiliated communities weighed how best to prevent similar effects in their lands.

The Villano Assembly launched OPIP's "Campaña Tungui" - invoking the drum rhythm which called allied groups to war centuries ago. The campaign outlined the conditions under which ARCO might proceed with its activities in Indian lands and declared a 15-year moratorium on further petroleum activity in the province. OPIP pressed for indigenous participation in environmental and social planning and monitoring, as well as the economic benefits of ARCO oil operations. Héctor Villamil, OPIP's president, rallied under the corrugated tin roof of a one-room school, "this assembly affirms our democratic zeal, for participation is precisely what we demand. We denounce current petroleum politics and insist that ARCO respect the territories of the indigenous peoples of Pastaza." A helicopter transporting drilling mud to ARCO's well flew over head.

In a pattern repeated wherever oil operates in Ecuador, the local community was divided. A handful of families loyal to OPIP invited Assembly participants to Villano. Yet a larger group materially supported by ARCO vehemently criticized the assembly and threatened participants. Indigenous opposition introduced risk to continued hydrocarbon activity. Tensions rose as OPIP leaders obstinately asserted their rights to convene in the area and overly zealous young men boasted of occupying ARCO wells, now militarized with seventy counter-insurgency troops. Villano encapsulated the political-economic reality animating petroleum development through out the Oriente: state dependency on oil, unmitigated military protection, multinational carte blanche, and local factionalism. Despite the power of corporate economic interests and indigenous peoples' circumscribed structural position, however, the Villano Assembly spurred into motion a process which ultimately conditioned - for the first time in Ecuador's seventy-year history of oil exploration - serious dialogue between indigenous peoples and a multinational over petroleum activity in Indian lands. OPIP leadership and community members began to re-articulate the relations between multinationals and local communities and influence the particular pattern of resource extraction in their territory. The Crude Challenge

In 1967, Ecuador launched itself into the industrial world with Texaco's discovery of a sizable oil reserve in the northern Oriente (as the Ecuadorian Amazon is called). Rainforest lands, previously seen as "empty," "barren" and awaiting colonization, became the source of Ecuador's black gold and the key to national modernization. In 1973, under the newly established military regime, Ecuador joined OPEC, and petroleum became a national security concern. With the influx of new petro-dollars and swollen aspirations to develop the country, the small Andean state became woefully dependent on petroleum. Today, oil revenues account for 50% of the national budget. All major petroleum reserves reside in the Oriente; transformations have been most acute in the northern lowland provinces of Napo and Sucumbios. There the exploitation of large oil fields has inscribed rainforest landscapes with seismic grids, over there hundred productive wells, more than six hundred open waste pits, numerous pumping stations, an oil refinery and the bare-bones infrastructure essential for petroleum operations. A network of roads links oil towns and parallels the pipeline for 500 km across the Andes to the Pacific. For the most part, oil companies have bought off local communities to facilitate the smooth flowing of their operations.

The negative repercussions of petroleum exploration and extraction are slowly becoming documented. In her comprehensive study of Texaco's 25 years of operation, Judith Kimerling calculates that since production began in 1972, Ecuador's trans-Andean pipeline has spilled an estimated 16.8 million gallons of crude - one and a half times that spilled by the Exxon Valdez. Likewise, petroleum operations discharge 4.3 million gallons of toxic waste daily. Recent studies document an increase in skin and intestinal disease, headaches and fevers among local inhabitants, and contaminants in drinking water which reached levels 1,000 times the safety standards recommended by the U.S. EPA. Despite public protest by Indians, colonists and environmental activists, President Sixto Durán Ballén initiated a formidable campaign to expand production. In 1992, Ecuador withdrew from OPEC in order to produce in excess of the cartel's quotas. All signs indicate that hydrocarbon activity will only intensify. Consolidating the Commons

Pastaza Province stretches from the central Andes eastward to the Peruvian border, covering 30,000 sq. km. Along the western-most portion, a 30 km-wide plateau flanks the foothills. Here, thirty years of colonization has transformed once forested indigenous land into a patchwork of pasture and agriculture. A network of roads connects smaller hamlets and colonist parcels to the provincial capitol, Puyo. Down the escarpment bordering the plateau's eastern rim, indigenous claimed territory begins - two million hectares of dense, yet managed, rainforest. The terrain is rugged, cut through with numerous river basins by the more than four meters of annual rainfall. Except for one 8km dirt road completed in 1993, there are no vehicular routes into the region. The indigenous populations living in the area inhabit dispersed settlements; the larger built around missions, schools and health dispensaries. Agriculture is largely subsistence with increasing production and harvest for market. This scenario markedly differs from the social and political-economic reality of the provinces directly to the north.

OPIP officially formed in 1978 as state pressure to colonize and develop Pastaza led to greater indigenous displacement. The Indian federation denounced state modernization strategies as destructive of cultural and ecological systems. Gaining communal title to Indian territory was the first step in asserting control over the processes negatively affecting indigenous livelihoods. Through the 1980s, OPIP actions halted colonization at the plateau and curtailed further incursions onto indigenous lands. It was not until 1992, however, when 2,000 Pastaza Indians marched to Quito demanding communal land rights, that indigenous peoples acquired legal title to over one million hectares of their territory. "The March" gained unprecedented popular support throughout Ecuador and signaled a sophisticated indigenous politics of resource use and territorial control. Significantly, it further crystallized the formations of an ethnic-national identity in the region, where livelihood forest management practices inform visions of resources use and social justice in the rainforest.

Yet, while land title precluded the further colonization of Indian lands, it provided no legal control over petroleum activities within them. Indians gained surface rights. Subterranean resources, of which petroleum is the most coveted, belong to the state which retains the right to develop them as it deems necessary. In 1988, ARCO acquired rights to explore an oil concession located 4in eventually adjudicated Quichua territory in Pastaza. In 1989, Quichua actions paralyzed ARCO exploration for one year. OPIP communities opposed to hydrocarbon activity charged that dynamite detonated during seismic exploration destroyed agriculture, scared away animals and killed fish. Operations resumed in 1990, however, allowing ARCO to identify pro-oil communities in the interim. In 1992, the company publicly announced its discovery of the province's first productive oil field. As it became increasingly evident that OPIP could not stop oil operations in Pastaza, the federation focused on how best to influence its development.

From OPIP's perspective, all attempts to negotiate with ARCO had decisively failed, despite moments of promise. ARCO refused to recognize OPIP as the legitimate representative body of indigenous inhabitants of the region. Instead, the multinational recognized and materially supported the pro-oil indigenous group that claimed to represent the three communities near the Villano wells. OPIP leaders interpreted ARCO's choice to legitimate a local "organization" newly formed in the summer of 1993 as an affront to their integrity and fifteen-year struggle to consolidate an indigenous politic. ARCO argued that the company felt compelled to support the communities closest to and most directly impacted by their operations. Yet, multinational representatives dismissed the fact that their presence spurred the emergence and continued existence of an anti-OPIP entity; corporate operations both facilitated and profited from dividing indigenous loyalties.

Beyond launching the Campaña Tungui, the Villano Assembly sought to demonstrate through practice how indigenous people envision their territory. Importantly, Indians spoke of territorio ("territory") or tierras ("lands" - in plural). This terminology reflects an understanding of landscape and property distinct from that of the state, where tierra ("land") refers to a commoditized, individualized, alienable object. Territorio ("territory"), by contrast, refers to ancestral space, the site of historically belonging within a lived landscape. More than simply connoting the physical contours of a region, territorio encompasses moral-cosmological and political-economic complexes which shape social relations with it. Forest management and resource use regimes reciprocally sustain these relations. Indigenous territory "belongs" to no one individual, as with free hold, who independently controls it. Rather, territory belongs to everyone; decision over processes affecting multiple inhabitants would have to be debated by all. Consequently, Indians espousing OPIP politics had just as much right to determine what was to occur in their lands as individuals who supported ARCO's presence in Villano. "The people near the oil wells do not own this land," explained Leonardo Viteri, the director of Amazanga (OPIP's research institute), during debate at Villano. "Nor does petroleum simply affect one community. ARCO's [concession] is 200,000 hectares; we all manage this land and will all be affected by oil." While concerns of those living near oil wells might take special consideration, proximity in and of itself granted no special rights. According to OPIP, a group of pro-production individuals lacked the authority to decide the future of petroleum activity in Indian lands. OPIP-affiliated communities gather in Villano to demonstrate that point. Cultivating Coalitions

Yet, dialogue between a multinational oil company and an Indian federation grew out of a broader trajectory of strategic coalition building between indigenous and environmental groups. In 1990, Acción Ecológica (Ecuador's most consistently programmatic environmental group) launched its "Amazon for Life" campaign, a watch-dog effort to denounce, document and redress the environmentally and socially degrading effects of oil development in the northern Oriente. Over the following years, Acción Ecológica and indigenous groups coordinated specific target actions with key support from U.S. and European environmental and human rights groups (especially Oxfam American and the Rainforest Action Network). Through an elaborate transnational network, Indian federations and Acción Ecológica heightened national and international scrutiny of multinationals operations in Ecuador. Momentum snowballed in November 1993, when indigenous and non-indigenous inhabitants of the northern Oriente filed a $1.5 billion class-action lawsuit against Texaco in U.S federal courts. Plaintiffs charged that the company's deliberate use of substandard technology to maximize profit in Ecuador over 25 years resulted in the massive contamination of the northern Oriente. Given the money involved and the press received, the suit and popular actions have alerted foreign companies that ignoring indigenous and ecological concerns has consequences.

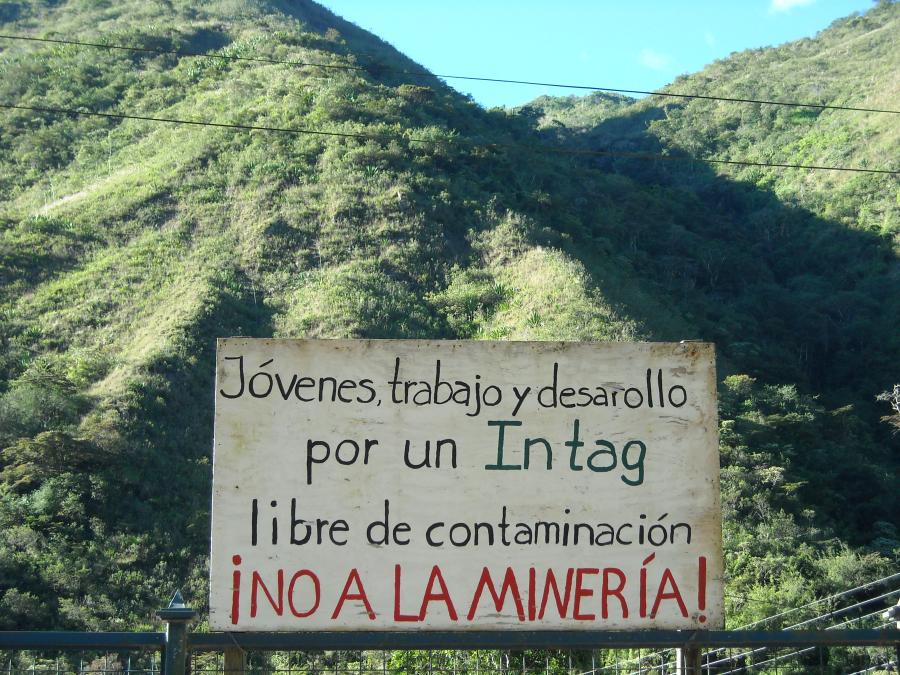

One month after the Villano Assembly, OPIP members in coordination with CONAIE (Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador), CONFENIAE (Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon) and Acción Ecológica occupied the Quito offices of the Minister of Energy and Mines. Their action fell on January 24th, 1994, the day the Ecuadorian government opened bedding for nine new oil concessions in the Oriente; four of the nine were located in Pastaza. Fifteen individuals positioned themselves inside the Ministerial quarters, refusing passage until the Minister agreed to discuss their concerns. Outside, approximately 150 protesters formed a human chain, impeding all traffic in and out of the building. In the city park across the way, demonstrators pitched tents and strung protest banners, symbolizing their resoluteness. As Luis Macas, the president of CONAIE, asserted, the occupation was in protest of the state's "incoherent petroleum policy" which "is contemptuous of indigenous peoples and provokes social, cultural and environmental conflicts." Protesters' politics were encapsulated in the broad green letters of a banner suspended between trees: "The Defense of Nature and Social Justice are Inseparable."

After a five-hour stand-off, the Minister met with protesters. Despite threats, the police were never called; keen on attracting foreign investors, the government did not wish to call attention to popular protest. Among the five demands presented to the Minister was the need for transparent and direct negotiations between ARCO and OPIP. The following morning, the Minister personally oversaw a meeting between ARCO and OPIP, clarifying the multinational's responsibility to engage in dialogue with the federation. While short of a Ministerial mandate, this meeting led haltingly to the eventual formation of a fragile, tripartite commission in September 1994 to design and monitor petroleum development in the Pastaza. Significantly, the commission includes representatives of an indigenous front of OPIP and anti-OPIP/pro-production groups, ARCO and the state petroleum company. Important changes from the prior pattern of oil exploitation discussed include: no road construction into indigenous territory; directional drilling allowing for multiple wells to radiate off one perforation; and containment of industrial chemicals, muds and solvents. Final outcomes of dialogues to mitigate negative social and cultural consequences of oil work are still pending.

Dialogue is still in its early stages. To date, ARCO and the state have not finalized details for the construction of a pipeline carrying crude to Pacific ports. Until that point, the company reasons it is unable to make future commitment with indigenous groups. ARCO has agreed, however, to finance an environmental impact study of the exploratory phase of their work. While a standard procedure in the U.S., an environmental impact study of their operations to date is not legally required under Ecuadorian law. This step is significant, theoretically, an evaluation of the social impact of ARCO operations must accompany analysis of environmental effects. Yet more significantly, OPIP succeeded in insisting that their communal lands be treated as indivisible territory; all Indians, not simply a small group near ARCO wells, must debate oil operations. Dialogue represents the recognition of the commons - the fact that local resource-use and access regimes differently structure decision-making processes over activity within a landscape. While an incomplete and unpredictable process, OPIP's struggle against environmental injustice and for participatory engagement is slowly controlling the process affecting indigenous livelihood and territory, setting precedence in Ecuador and for the Amazon region. Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.