According to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous communities have the right to give their Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) to proposed projects that may affect their lands, resources, livelihoods, and communities. This means that Indigenous communities have the right to decide whether to allow companies or governments

to mine, deforest, or in other ways develop their lands, and they have the right to make informed decisions through culturally relevant processes based on their right to self-determination and sovereignty.

The central project of the Cultural Survival’s FPIC Initiative is an innovative radio series for free, worldwide distribution to help Indigenous communities be better informed about their right to FPIC and be more prepared to assert it. One year in, the initiative is going strong: 28 programs on Indigenous Peoples’ right to consent to exploitation of their lands, territories, and resources have been produced in English and Spanish by four Indigenous producers, plus additional programs on general Indigenous rights produced at the World Conference on Indigenous Women and other events.

Programs have been translated into 13 Indigenous languages plus Nepali, and several more Indigenous language productions are in progress. Programs have been distributed to over 500 Indigenous radio stations. Many translators have taken on the task of directly translating Cultural Survival’s programs into their own languages, which includes both translating words and interpreting ideas in culturally appropriate ways.

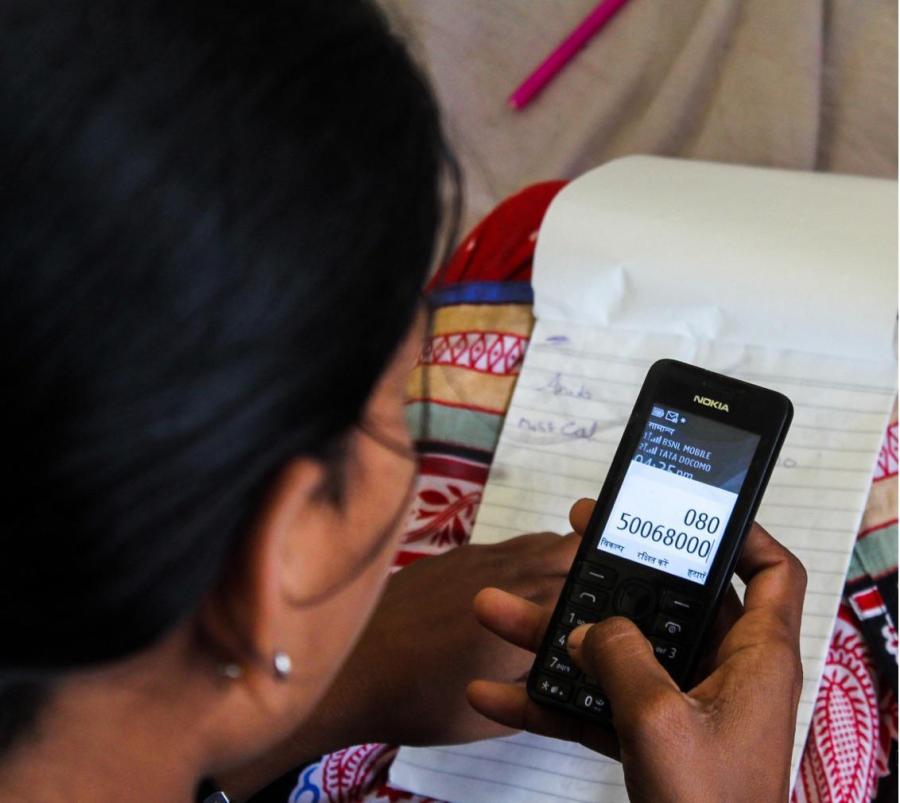

Shamanthaka Mani is an Indigenous Kannadiga radio producer from Karnataka, India. Mani has put a unique spin on the production and airing of FPIC material; instead of simply translating Cultural Survival’s programs into Kannada, she built a 45-minute Kannada language interactive program around the English-language public service announcements to more deeply involve listeners. Mani details the process: “First we played the English PSA. Later, I built programming around it from the Indian and Karnataka context. This was a general introduction in simple language without any jargon, taking a few national and state-level incidents as examples. For instance, converting agriculture land for either construction or setting up industries. In our Indian context it is called SEZ, or Special Economic Zone, which is a new policy by our government and has created a major uproar in the country. We explained incidents which happened in West Bengal and also in North Karnataka. I also made an effort to convey to the listeners that these types of issues are global and just

not restricted to Karnataka or India; they are common phenomena even in advanced countries.

This comparison is required psychologically to convince our rural audience to understand similar situations from global perspective. The emotional comparison made them think and analyze from a human angle. This was a technique to educate them about how governance works in human related issues, and was a new approach for our rural RJs (radio jockeys) as this

program made them understand rights, Indigenous people, peace, human rights, accountability, etc. Later, I trained my RJs especially how to deal with these particular issues at the local level—making them understand by talking about our local issues, state government policies, and their effects on rural life was the focus of our program. During the program I asked them to share their experience and views about that particular issue.

This project is an innovative approach to how to treat and convert a global issue into a local issue. Our listeners have interacted, responded, and participated in human rights, development projects, agriculture, and UN Declarationrelated subjects. I enjoyed conceptualizing the project and am sharing it as an example in a OneWorld content development

workshop as a resource person.”