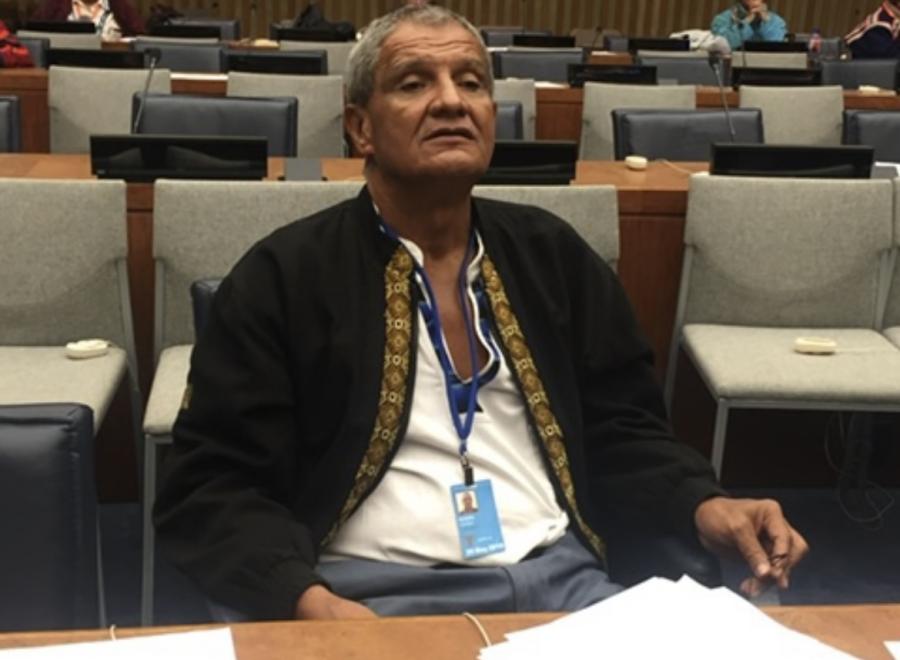

Miskito leader Brooklyn Rivera was invited to return to Nicaragua to negotiate the return of some 20,000 Nicaraguan Indians now living in exile.

After Nicaragua's Miskito Indians stepped onto the front pages of newspapers throughout the world in early 1981, their representative body, Misurasata, gradually became the most well-known Indian organization in the Americas. But it acquired much of its fame for all the wrong reasons. Rare was any association between Misurasata and the rights it was formed to defend, e.g., control over land and natural resources and a degree of political autonomy for the approximately 90,000 Atlantic Coast Indians. Instead, attention focused on Misurasata's dramatic, armed opposition to the Nicaraguan government. About 2,000 Misurasata guerrillas have battled government troops throughout the Atlantic Coast for over three and a half years. Misurasata has thus been cast into the arena of the East-West conflict now used to explain most conflict in Central America. As such, many of the Nicaraguan government's critics dub the Indians freedom fighters, simply because they battle the Sandinistas. Nicaragua's supporters, by contrast, refer to the same guerrillas as CIA-backed counterrevolutionaries led by a small clique of irresponsible and unrepresentative opportunists. Such imagery began to fade recently as Misurasata worked to reassert its original, leadership role.

On October 20, 1984 Brooklyn Rivera, Misurasata's General Coordinator, flew from Costa Rica to Managua, entering Nicaragua officially after more than three years of self-imposed exile. His arrival marked the beginning of talks aimed at ending Indian guerrilla fighting and reestablishing Misurasata's role. Following initial meetings with Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua's Head of State, and Luis Carrion, Vice Minister of the Interior, Rivera, accompanied by two other Indian leaders and seven international observers, visited Miskito, Sumu and Rama Indian communities and resettlement camps throughout Nicaragua for 12 days. The trip was designed to observe conditions on the Atlantic Coast and to reestablish contacts with government officials and Indians; no formal agreement was anticipated or obtained. Nevertheless, the visit demonstrated strong support for Rivera among Indian communities, and a desire on the part of the government to resolve the conflict as quickly as possible. At the end of the visit, in a mutual goodwill gesture, Rivera coordinated a dramatic release of three government officials captured by Misurasata fighters while government officials released three Miskito prisoners involved in the 1981 shootings in Prinzapolka, the incident which sparked subsequent violence between Indians and Sandinistas. Upon returning to Costa Rica, Rivera met with Indian leaders there. Later, Misurasata officials hope to travel to Honduras for talks with the remaining refugees and exiles. Rivera plans to meet again with Carrion, probably in Colombia, to begin formal negotiations in November or December.

Background to the Peace Initiative

Although both Misurasata and the Nicaraguan government had requested negotiated or mediated peace settlements, specifically through the OAS Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), no progress had been made since fighting erupted. The IACHR originally agreed to Nicaragua's request to act as mediator in a "friendly settlement." But, 2 years later, IACHR terminated these activities, indicating that one of the principle reasons for its decision was Nicaragua's refusal to negotiate with certain Misurasata leaders. Meanwhile the violence escalated from occasional border skirmishes near the Rio Coca in 1981 to widespread warfare throughout the length and breadth of the Atlantic Coast by 1984. And accusations of widespread human rights violations increased.

Neither Misurasata nor the Sandinistas expected a decisive military solution; while Nicaraguan army strength exceeded that of Indians, guerrilla fighting had been damaging and many local communities supported the Miskito soldiers. A prolonged and debilitating struggle appeared likely, but appealed to neither side. Despite public refusals to negotiate with Misurasata, initial peace overtures on behalf of the government were extended quietly to Rivera by Moravian church leaders in July 1984. Rivera, however, insisted on statements from high ranking government officials. During the last week of August 1984, Mr. Ortega responded indirectly. At a rally in Puerto Cabezas he stated that Rivera was welcome to return under the general amnesty of December 1983. Rivera subsequently issued a statement expressing a willingness to return if the government agreed to free imprisoned Indians, recognize Misurasata, and discuss regional autonomy and land rights. Although no formal response was received. Carrion subsequently directed the Nicaraguan Embassy in Costa Rica to expedite any request by Rivera to return to Nicaragua.

To obtain political support for an initial visit Rivera approached various external authorities, among them US Senator Edward M. Kennedy. Kennedy's aide, Gregory Craig, then invited Rivera to the US (travel funds were provided by the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee and Cultural Survival) to meet privately with Kennedy. The same offices then arranged a secret October 3 meeting with Mr. Ortega, in New York to address the UN General Assembly. The meeting was successful; an invitation to return to Nicaragua was extended and accepted. Shortly thereafter Rivera approached Regis Debray, French President François Mitterand's advisor on Latin America, who obtained his government's support and aid for the peace initiative. At the request of Misurasata, Cultural Survival provided airfares and travel funds for the Indian delegation's trip to Nicaragua.

The Trip's Significance

On one level, that of most immediate concern to the Nicaraguan government and most noticeable to observers of recent events in Central America, the trip signalled the beginning of an end to Miskito guerrilla warfare on Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast. Although Misurasata fighters are not the only forces active in the area (in fact they are among the smallest of several groups), they enjoy broad support among coastal communities and, unlike other forces battling the Sandinistas, they have received much attention from international human rights organizations. Other, truly counterrevolutionary organizations have sought to establish alliances with Misurasata and thus capitalize on its positive image. Misurasata's peace initiative therefore weakens the appeal of the other forces and contributes toward a broader peace in the area. The exchange of prisoners was thus a significant, although symbolic, step toward the resolution of the conflict and, accordingly, received considerable attention. However, by focusing on such actions, observers emphasize only the violence rather than its causes. This blurs the original stimulus for the formation of Misurasata and thereby fails to illustrate how the organization's dramatic present situation is analogous to that of Indian organizations throughout the hemisphere.

For Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast Indians an end to the fighting is, of course, an immediate concern. But any peace settlement will be short lived unless Misurasata is allowed to reestablish its primary role and thereby confront the root causes for the violence. To illustrate, four demands formed the basis for Misurasata's preliminary discussions. Two demands related only to Rivera's trip - security precautions and guarantees of free movement and speech. The other two concerns - the recognition of Misurasata as a legitimate Indian organization and a willingness to negotiate local autonomy and land rights - are critical to the entire present and future Indian population of the Atlantic Coast. For the moment the details of these demands have been left unspecified, purposely. They will emerge as formal negotiations proceed. However, even at the most general level they illustrate major differences between Misurasata's concepts of regional development and growth and those of the government. Such differences are obvious with regard to land and resource rights.

Land and Resource Rights

Resource rights, to a limited extent, are recognized by the government.

The natural resources of our territory are the properties of the Nicaraguan people. The Revolutionary State, representative of the popular will, is the only entity empowered to establish a rational and efficient system of utilization of said resources. The Revolutionary State recognizes the right of the indigenous communities to receive a portion of the benefits to be derived from the exploitation of forestal resources of the region. These benefits must be invested in programs of community and municipal development in accordance with national plans.

That is, rights to natural resources are recognized only to the extent that the community whose land contains the resources receives a percentage of their value when they are removed from community property. Community members stated that they were powerless to determine whether or not resources will be exploited. Timber, for example, is cut extensively within many Indian communities in northeastern Zelaya, and there are well developed plans and programs to expand such activities. No contract is signed prior to the cutting. Loggers enter, clear the timber, and truck it to Puerto Cabezas. There the log value is calculated and the community is credited with 80% of that value. Government liaison officers (CDS) in several communities indicated that they had no idea of the value of cut timber and relied on the government to inform them of their assets. The funds are said to be deposited in a bank and can be withdrawn when an acceptable community project is formulated. Several community officials, however, complained that these funds had proved impossible to obtain. Misurasata was formed to resolve such problems; the organization had signed a formal lumbering agreement with the government in February 1981.

Land rights are also recognized officially. The Popular Sandinista Revolution will not only guarantee but also legalize the ownership of lands on which the people of the communities of the Atlantic Coast have traditionally lived and worked, organized either communally or as cooperatives. Land titles will be granted to each community.

In practice, however, the situation appears quite different. In late 1980 the Nicaraguan government agreed to let Misurasata prepare a land claims study which was to serve as the basis for negotiating the boundaries of community land holdings. Cultural Survival provided funds to undertake this survey. But in February 1981, several days before the study was to be presented, Misurasata leaders were jailed, temporarily, on charges of planning a separatist plot. When released, all except Rivera went into exile. The following July new Nicaraguan agrarian reform laws stated that the government would determine and allocate land rights on the Atlantic Coast, a direct rejection of the earlier agreement with Misurasata. A week after the law was made public Misurasata claimed aboriginal rights to 45,000 Km(8) of land. Shortly thereafter Rivera declared that he was unable to work safely in Nicaragua, and went into exile. On August 12, 1981 the FSLN and the GRN published the Declaration of Principles regarding Indians of the Atlantic Coast, placing control of most Indian affairs in government hands. This significantly affected land rights.

When border skirmishes increased in late 1981 and early 1982, the Nicaraguan government, in February 1982, forceably relocated about 8,500 Miskitos from communities along the Rio Coco to four resettlement camps about 60 km to the south, an area now known as Tasba Pri. The expressed purpose of the move was security; on the one hand to guarantee the personal safety of the Indians living in an area of increasing violence and, on the other hand, to make sure that these communities did not become staging areas for guerrilla groups, many of which included Miskitos from the Rio Coco communities. For the same expressed reasons, the government, from November 22 to December 22, 1982, evacuated 685 Sumu and 506 Miskitos from communities near the headwaters of the Rio Coco. This time, however, the relocation was from riverine communities to state-run coffee and cattle estates (Unidád de Produción Estatal, or UPE) in the departments of Jinotega and Matagalpa, over 150 km to the southwest and into high, cool, coffee growing regions. Here they occupy cramped, dark barracks built by previous landlords to house seasonal laborers, and work on the surrounding coffee plantations. These communities are being transferred slowly to government constructed settlements similar to those of Tasba Pri. Eventually they will obtain title to lands, excised from the surrounding UPSs, for coffee production and cattle raising.

Residents of Tasba Pri and the Matagalpa-Jinotega resettlement areas stressed that their foremost desire was to return to their homes on the Rio Coco. Government officials said that they would be free to do so when the current military threat disappeared. Pressed on the issue, however, officials indicated that even if the current fighting ended, a latent threat would remain as long as Nicaragua feared an invasion across the border. There was, therefore, no plan to return the population to the Rio Coco. Quite the contrary, all efforts were being made to create permanent communities geared toward market-oriented economic activities. Permanent housing, health centers and schools have been established. Government publications no longer refer to Tasba Pri as a temporary camp. The settlements are regarded as communities on a par with other production centers in the area. The population of Tasba Pri is already the fifth largest in Zelaya Norte and over 83% of the land titled in Zelaya Norte since July 1979 (approximately 15,000 hectares) has been awarded to residents of Tasba Pri. Only five other communities have obtained land titles, totalling about 3,000 hectares. Moreover, with an agricultural storage capacity of 20,000 quintals, Tasba Pri is second only to Puerto Cabezas, the capital and hub of the region. Four hundred hectares have already been cleared for production and, in rice alone, the harvest is expected to yield over 10,000 quintals.

The Rio Coco communities were not relocated onto arbitrarily selected lands; land use maps in the regional government offices indicated that the Tasba Pri settlements have been clustered within a small sector of land considered to be the only area suitable for intensive agriculture in the region. All Tasba Pri communities lie near or alongside the single road which joins the Atlantic Coast to the capital. Similarly rich, accessible lands in Jinotega have been set aside for the population relocated from the headwaters of the Rio Coco.

In an official government publication Fr. Augustin Zambola stated, "[The Tashba Pri relocation] is not a new plan but something which has been foreseen two years ago for the improvement of conditions of these communities". That is, as early as 1980, a development scheme had been prepared to relocate many isolated Rio Coco communities to areas where soils were considered to be more fertile and where access to national markets was easier.

Such dramatic changes in the Indians' livelihood, land tenure, settlement patterns and participation in the national economy are the dream of many national planners. Almost overnight groups regarded as isolated, relatively unproductive populations are being drawn into the national society, regardless of their desires. The government has a clear idea of how land and labor should be organized; Indians will not be deprived of access to land and resources but it appears that the government will decide where they obtain that access and will determine how Indians obtain benefits from resource exploitation. Communities thus become labor camps.

Such designs are in sharp contrast to Misurasata's statement on land holding.

The right of indigenous nations over the territory of their communities supercedes the right over that territory by the state...any sovereign nation state should recognize, without discrimination, the inalienable right to territory belonging to the indigenous nations that are to be found within their respective national territories.

Until such contradictory concepts of land tenure are reconciled and until the Indians of Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast are allowed a voice in determining the nature and scope of economic change in their territory, the roots of the current violence will remain exposed and any effort to achieve peace will be tenuous.

Aware of this, Rivera demanded: 1) a willingness to discuss local autonomy and land rights (demands voiced by Indians throughout the hemisphere) and; 2) recognition of Misurasata (the form of organization needed to define and negotiate these rights). Such priorities belie charges that Misurasata is unrepresentative of local communities or irresponsible with regard to their needs. Moreover, by undertaking the peace initiative only after assurances by Mr. Ortega that such demands would be met, and travelling to Nicaragua despite strong opposition or threats from all of the other groups fighting the Nicaraguan government (ARDE, FDN, and even the US Department of State), Rivera demonstrated that the Indians are not pawns in the East-West struggle. Their thwarted needs have simply been obscured by a larger shadow. The peace initiative has drawn these issues into the light again. If they can be negotiated successfully, the sovereignty of both the Miskito people and the Nicaraguan nation will be more secure.

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.