By Verónica Aguilar (Mixtec, CS Staff)

Yesenia Montes, from the Puriyninchik Collective which runs a library and an independent publishing house, tells us in an interview why her community started publishing books in Quechua in Peru. The Collective's work represents an inspiring example of writing and editorial techniques for community purposes, collective use, and community creation, far from the economic interests and elitism that has been created around the written language and book culture. The materials that the collective produces are being used from the very beginning, because there is an identity and cultural closeness between the community and the book.

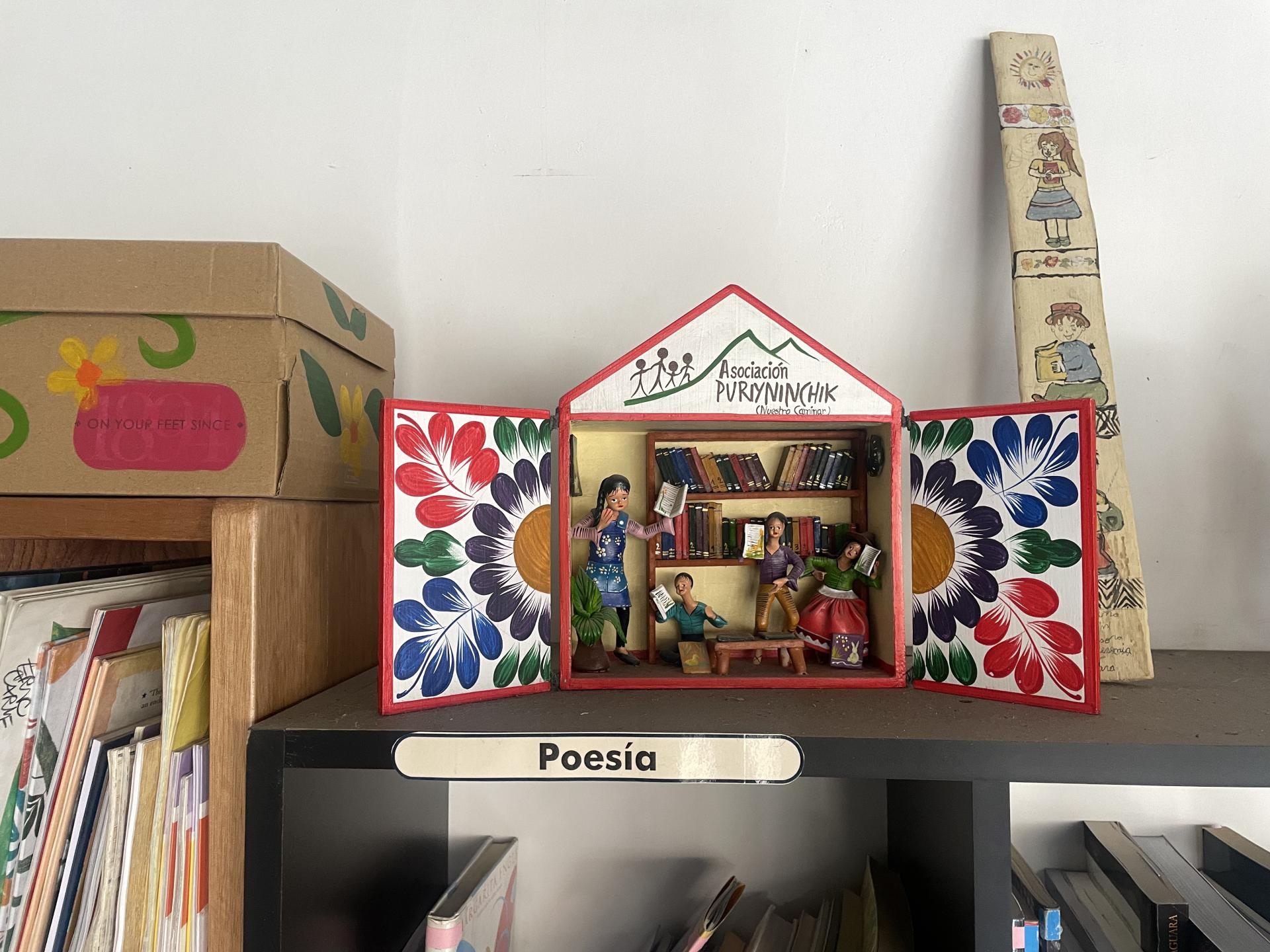

"In my rural community, I realized that, after reading a book in Spanish, the children commented on the reading in Quechua. Then I asked myself why we didn't have books in Quechua in this library." Theirs is a traveling library that is transported in a wooden altarpiece, an expression of traditional art from the Ayacucho area in Peru. Montes’ father, a carpenter, designed the altarpiece so that it closes on itself like a suitcase and thus serves both to protect the books during transport and to attract attention and connect with the local Quechua identity.

After identifying the need to integrate books in their language, they wanted to obtain some. "I naively believed that I could buy them, so I went back to the city and looked for children's literature [in Quechua]. I was frustrated because I couldn't find any. It's incredible, we have 200 years of supposed freedom and still no quality children's literature has been published that takes care of the illustration, the text, the game, the rhyme, in our native languages."

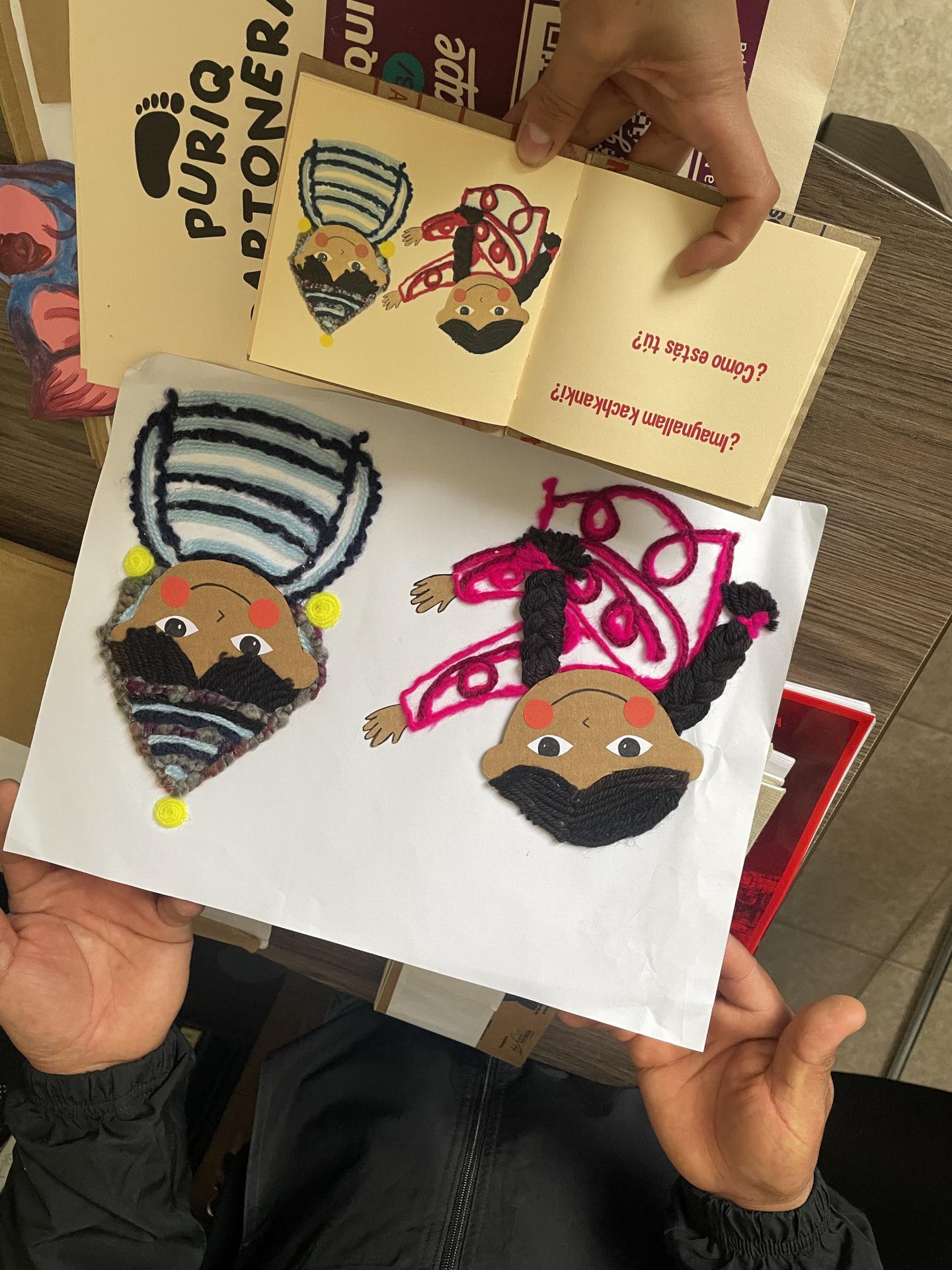

That's how they decided to create their own books, not only the members of the Collective, but also with the participation of members of the interested public and, above all, children. "We want books that inspire children to create and break the mold, to know that they can also be protagonists, to say in creative ways what they think and what they dream." The members of the Collective now appear in public places to give readings in Quechua and teach how to make cardboard books. They invite the public to read and create, and, above all, they want children to be encouraged to write and publish their stories.

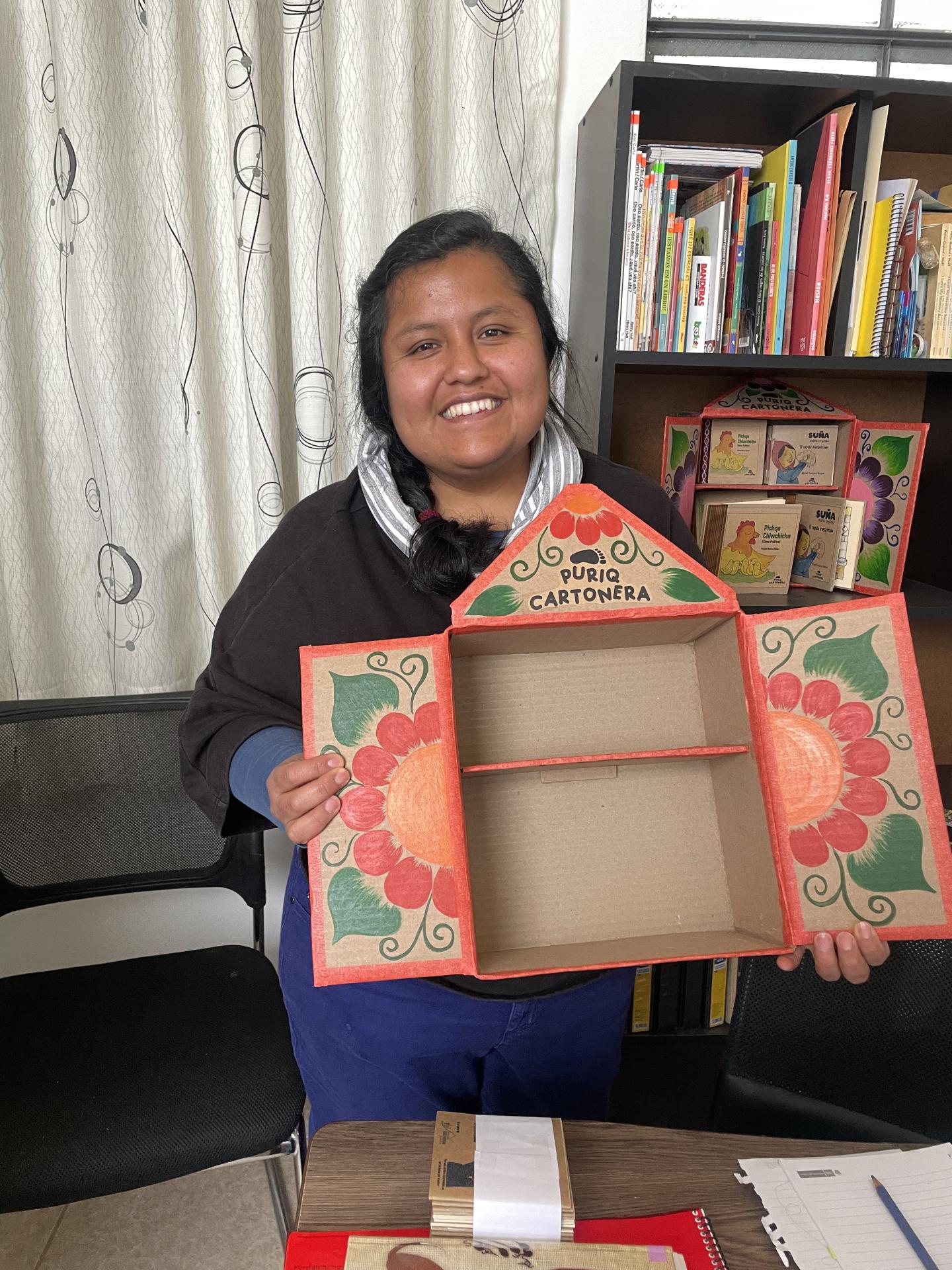

The members of Puriyninchik have been working for four years on what they call their "cardboard publishing house," which publishes books with all kinds of materials, such as cardboard, wool, hand-drawn illustrations, and practically any material available, even recycled materials. The books are inexpensive but of great quality, have ISBN registration, and are concentrated in small print runs since handwork requires time and dedication. They have published in Quechua and Spanish, and they also have bilingual editions.

The Collective also runs a library in Huamanga, where a collection of books is organized in a non-traditional way: they are separated by shelves according to the type of reader they are aimed at. There are books with more or less text, with more or less illustrations, books with only images, and books in Braille. The goal is for the library to be an open space for exploration, where readers can be encouraged to open any book and use it for their purposes.

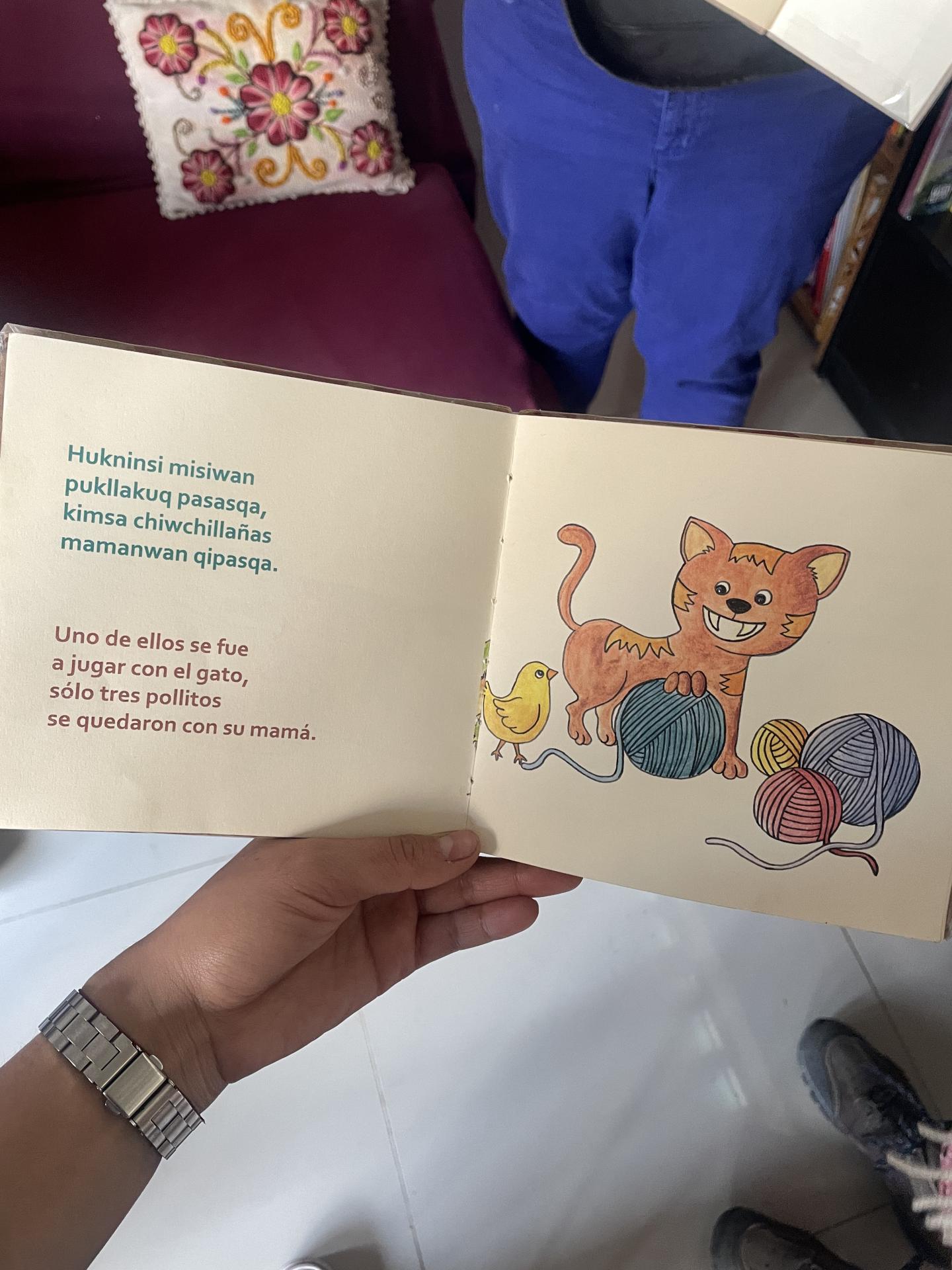

During the interview, Montes shared with Cultural Survival a very special book for her, “Pichqa Chiwchicha (Five Little Chicks)," a story inspired by a Spanish story about ducks. "I adapted the story with chickens, which is closer culturally. I put things that in my Andean world terrified me that would happen to my chicks. So I put music to it and remembered all the songs I grew up with," Montes says.