By Bety Piche (Zapoteca)

Oaxaca is "the land where God never dies.” Its inhabitants know it by its great cultural and linguistic diversity. It is also a place where the complete closure of downtown businesses due to Covid-19 affected the economy of traditional handicraft artisans in the capital’s historic center.

In March 2020, Oaxacan authorities declared the closure of schools, businesses, local government offices, and others without guaranteeing basic services for the community’s survival. These measures obligated traditional artisans to suspend activities until July, despite their economic needs, without any government assistance.

The main road of the Oaxacan state capital starts in Zocalo, passing through the "Macedonio Alcala,” a tourist area, and ends at the Santo Domingo de Guzman temple, where about 60 percent of the artisans and vendors renting stalls have returned since July 2020.

Even though artisans are back at work, there is still a crisis of shortages and they lack the essentials to produce their handicrafts. Still, they reinvigorate themselves and renew their creativity by designing unique, original pieces.

Above, a Nahuatl speaking woman along the tourists' walk from Guerrero state. She designs hats made of ixle, the generic name for plant fibers used to produce weavings and ropes. One of the reasons she remains in Oaxaca is the economic opportunity that tourism offers.

An artisan woman produces a handmade hat with liana, a woody vine. It is a climbing plant found in hot and temperate climates and grows near rivers and streams. Stalks of this climbing vine are used for making woven basketry.

Artisans paint, decorate, embroider, and weave as activities of resistance. These spaces allow them to make the most out of their artisan activities. For some, it's a second job. For others, it's an activity that reinforces their ancestral knowledge.

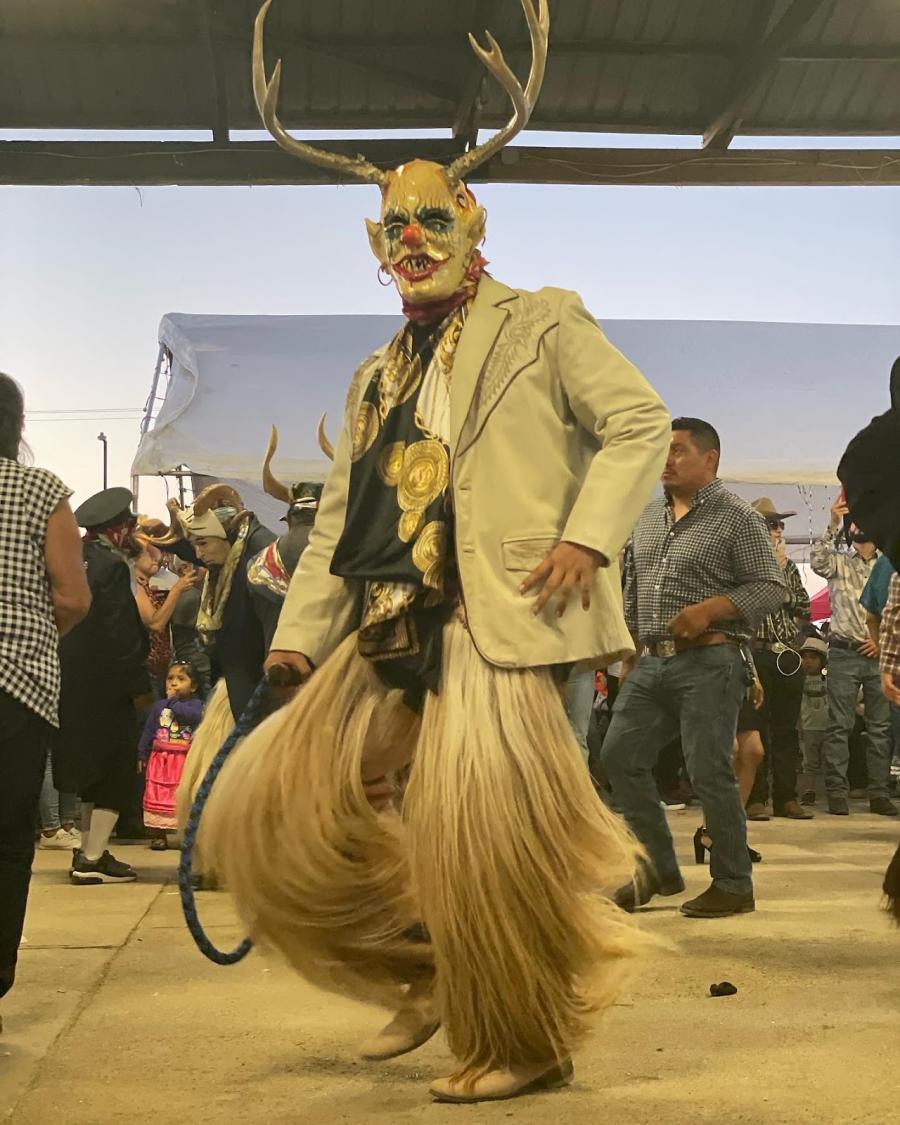

The market stalls showing the clothing from diverse Indigenous communities reflect each artist’s talent. In in just one tourist spot, we can get to know the eight regions (Cañada, Costa, Istmo, Mixtec, Papaloapan, Sierra Sur, Sierra Norte, and Valles Centrales).

The artisans offer a variety of shawls, blouses, overcoats, dresses, vests, shorts, and other clothing woven by women and attractive to both men and women visitors.

One can enjoy a space dedicated to basket weaving where artisans use palm and liana to make decorative baskets for tables, collection boxes, handbags, hats, and other women's accessories from the Indigenous Mixtec communities.

The communities of the state of Oaxaca live sustainably and harmoniously with the environment. The products reflect the relationship with Mother Earth and the environment. We can find tablespoons, mortar and pestles, plates, cutting boards, and kitchen utensils in their list of products, all from the Costa Chica communities in Guerrero and Oaxaca.

The Triqui culture has a particular way of weaving the products for sale. Threads of all types and colors make their weavings more attractive. Amongst their products, we find wallets, barrettes, hat bands, hair bands, and garlands for adorning women's hair, all delightful offerings from the Triqui culture.

Claudia, an artisan originally from Miahuatlan, Oaxaca, is from the Indigenous Zapotec people. Since April, she has noticed more connections with her fellow vendors and sees hope for the future after the pandemic. April is the month when more tourists arrive, since it is vacation season.

The pandemic was critical and destructive because it forced artisans to leave their work and look for other employment sources to cover basic expenses. The Mexican government continues to ignore to this sector's situation, as with most other groups in our society, who have all been affected for more than a year now.

A portion of the artisan community has returned to fulfilling a difficult role. The hope is that this return normalizes the economy again and that Oaxacan enterprises continue their economic potential in the heart of the capital.

--Bety Piche (Zapoteca) lives in Oaxaca México and is originally from the community of Villa Hidalgo Yalálag. She is part of a collective of young Indigenous people belonging to different Native Peoples of Mexico who have migrated to Mexico City. Piche was a participant in the project “Training Indigenous Women to Defend their Human Rights,” a series of workshops on communication and human rights held between March and June 2021 by Cultural Survival and the Alumni Engagement Innovation Fund. The topics of the trainings included healing, information, and documentation of individual and collective human rights. Different media were used to document and communicate human rights violations, including writing, photography, video, radio, and social media. This photo essay is the result of Piche's final training project.