The island nation of Fiji has long been a crossroads in the South Pacific, where ancient canoe-voyaging neighbors, shipwrecked European explorers, and modern multinational corporations have impacted its shores. Under British colonization, iTaukai (Indigenous Fijians) experienced the repression of many traditional beliefs and practices, including the marginalization of their own language, while forced to make room for the Empire’s importation of indentured laborers from India. Though it gained independence in 1970, the country’s political stability has been rocked by four coups d’état since then, sparking the rise of an active civil society sector speaking truth to power—which, in Fiji, lies not only in the hands of elected officials, but its Great Council of Chiefs and the Church. Women’s rights groups have long led the charge for social change, and the LGBTQIA+ community is increasingly asserting itself as well, finding the literary and arts scenes to be safe spaces for dialogue and collaboration as well as for beauty.

Poet and activist Peter Sipeli has become a leading figure in these interconnected realms while contributing much to the further development of Fiji’s creative sector by curating spaces and literary events. He performs regularly and, beyond his own numerous works in print, is publishing a forthcoming anthology featuring the country’s emerging poets. He cites storytelling as a key tool for community engagement in his advocacy work, which he shared in a TEDxSuva talk. Cristina Verán recently spoke with Sipeli.

Cristina Verán: How do you identify, in terms of where you come from and the spaces you inhabit in Fiji?

Peter Sipeli: Traditionally, when introducing a person here, you state their place of origin, family name, and name. I’m from Lau [the island], Vanuabalavu [the district], Sawana [the village], Sipeli-Rakai [family name], the son of Tawelu, and lastly, my name is Peter. That maps me in a Fijian context. On my father’s side, I also have lineage from Tonga, as well as some from Samoa, the Solomon Islands, and Scotland via mother. I was raised and reside currently in Suva. I also identify as a gay man.

CV: What does Suva represent in terms of regional context and as an urban island space?

PS: Suva is kind of the epicenter, being a port of entry. It’s also a base for all those large, ghastly international donors [EU, AusAID, USAID] and fancy UN agencies—complete with cargoes of white international experts that shape development here. As home to the University of the South Pacific, this city also hosts the largest Pacific Island student population in the region. And it’s been central in regard to the circulation of poetry and literature, not only in Fiji, but across the region.

CV: Please tell us a bit about your own experience there, especially with regard to the LGBTQIA+ community.

PS: I was among the first cadre of gay people that stood up— and by this, I mean being “out” and visible—when we began the first real gay lobbying group here to openly advocate for our equal rights. Before 1999–2000, there were really no politically active organizations. Socially though, there was the Miss Gay pageant, and nightclubs here would often host elaborate gay-themed nights and drag shows. Gay and trans people are more accepted for making money as performers, rather then being actually allowed their own safe public spaces. That scene has alas been more about gay men and trans women, not celebrating lesbian cis women.

CV: Indigenous cultures around the Pacific have historically embraced the kind of identities that the West would ascribe to the LGBTQIA+ spectrum, for example, mahu in Hawai’i, fa’afafine in Samoa, and so on. What about in Fiji?

PS: English colonizers did a very thorough job of indoctrinating our people into Christianity, to the point where now Fijians see aspects of our own pre-European contact culture as ‘demonic’ and ‘pagan.’ It’s very difficult in Fiji to even have a conversation about our Indigenous traditions of being, for example, vaka sa lewalewa (in the spirit of a woman); what Native Americans might call Two-Spirit. So much of this kind of knowledge has been lost.

CV: In terms of the law, what challenges do you face and how have you and others sought to overcome them?

PS: In the late 1990s, we activists built a close relationship with the Fiji Human Rights Commission to advocate for our protection, safety, and equal access. The issue of love is really important, too. Where are people like me able to go to find love? In 2000, a bill was put before the then-newly elected Labour government of Mahendra Chaudhary to amend the Fiji Constitution and bill of rights regarding sexual orientation and the right to marry. That government was toppled by a civilian coup that held Fiji’s Parliament hostage, after which the military came into power to run the country (the leader of which, Josaia Voreqe “Frank” Bainimarama, remains Fiji’s Prime Minister). The new regime proposed an amendment to disallow marriage for non-heterosexual people, so we took to the streets.

CV: Your creative voice emerged from your activism. How did that journey begin?

PS: I have always been an ally to women’s activism, even before I could fully comprehend my presence in those spaces, as a volunteer with the Fiji Women’s Rights Movement and for a community theater group called Women’s Action for Change. They wholeheartedly supported our [LGBTQIA+ focused] work and offered us our own space. It was at the Fiji Women’s Crisis Centre that I started to use storytelling in my work, a way of talking about lived experience to create a deeper understanding of the need for equal rights from a more ‘human’ perspective.

CV: Tell us about the poetry scene in Suva, its history and social and political contexts, and also your beginnings within it.

PS: In the late ’60s/ early ’70s, the first wave of contemporary Pacific writers—people like Albert Wendt, Konai Helu Thaman, and Epeli Hau’ofa (founder of USP’s Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture)—were writing against the colony. As our countries were gaining independence, they responded to a global call to write in our words, with our own worldview, remembering our knowledge. The second wave looked at issues impacting the region, a nuclear-free and independent Pacific, rethinking Pacific education, the role of women in society, the impact of development, etc. And now in this third wave, we’re looking inside, at ourselves; a more insular kind of writing.

Poetry was something I’d initially done on the sly, just for me. But I became good mates with and inspired by people like [poet and scholar] Teresia Teaiwa, for example. Gary Apted, a friend to many in the scene, had opened the doors of his nightclub, Traps, to host the first public poetry readings in Fiji. It was there that I got to hear Hau’ofa read his poems and see Luisa Tora’s early performance pieces—especially one about “building a closet.” They were the masters; part of what would become the Niu Waves collective, which included other important voices like Cresantia Koya [a.k.a. OneAngry Native], Susie Sela, etc. I knew I wanted to share my work with that kind of crowd. When our slam poetry scene developed soon after, I was reborn.

CV: In this International Decade of Indigenous Languages, how present is Fijian in today’s poetry?

PS: The scene here happens mostly in English, although Apolonia Raitamata, a Fijian academic, does read exclusively in Fijian. It’s an issue of fluency, really. Fijian is a very complex language. I think poets also use English because they feel able to write more openly and easily about certain issues. Though I never write fully in the language, I do use Fijian terms and phrases in my poetry. There’s a piece I perform—“Maps to the Ancestors”—accompanied by an audiovisual recording of a vucu (a male chant, in Fijian) written specifically for the piece, played in intervals between each poetic verse.

CV: You’ve contributed significantly to the development of spaces, events, and publications to support the movement. Please share a few highlights.

PS: I founded and published ARTtalk Fiji magazine and founded Poetry Shop Fiji, and also a new poetry network that manages slams, readings, and monthly circles for poets and writers to find not only a sense of community but also a sense of safety to share work that may speak to their sense of isolation and ostracization. At the moment there aren’t any queer women’s voices in the scene, or rather, if there are, they’re not “out,” not even to me. I’m publishing a forthcoming Poetry Shop Fiji anthology featuring emerging writers called #DontStepOnTheMat. In a Pacific cultural setting, you try your best when you walk into a space to not step on the good parts of [traditional, hand-woven] floor mats, thus being respectful of others and the elders. In this case, it means to be careful and respect this space.

CV: What is next for you?

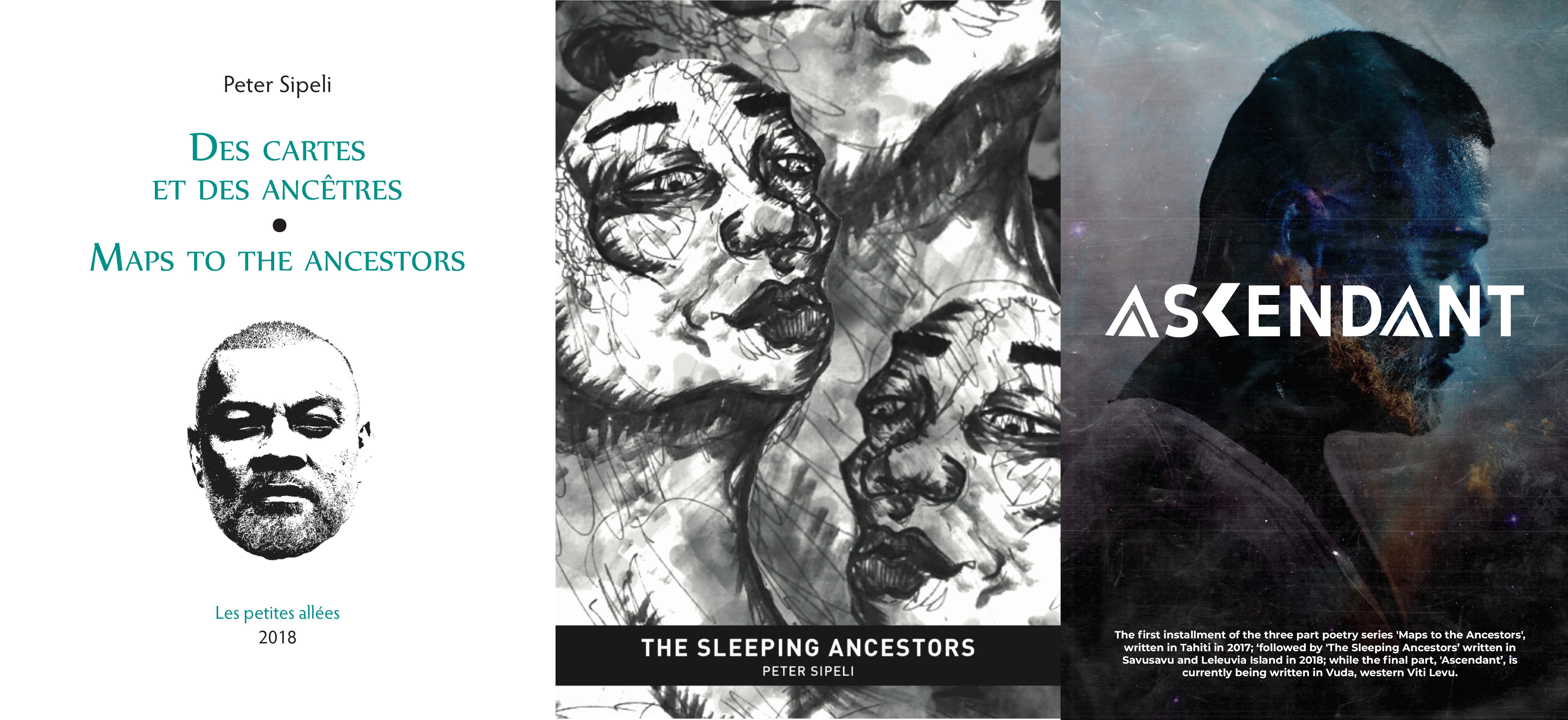

PS: I’m finishing the final book in a three-part series. First was Maps of the Ancestors, then came Sleeping Ancestors, and next will be The Ascendant, in which I’m talking to a “future me.” In 2020, I’ll spend at least eight months away at international residencies, including Parasite Gallery in Hong Kong, Vunilagi Vou Gallery (run by Emma Tavola, who is also Fijian) and Te Papa Museum in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the Festival of Pacific Arts in Hawai’i, and finally to Geneva for the Foundation Jan Mikalski residency for writers.

Cristina Verán is an international Indigenous Peoples issues specialist, consultant, researcher, strategist, curator, educator, and media maker. She is a longtime United Nations correspondent and was a founding member of the UN Indigenous Media Network.

Top photo from the inaugural TEDXSuva by Joseph Hing.