Activism is a business. Fair trade organizations are learning that their movement for fair and sustainable labor practices requires good business sense -- not just good intentions.

Simply put, fair trade advocates want workers to be paid adequate wages and have good working conditions rather than be subjected to market pressures. The success of the fair trade industry, particularly in the coffee trade, is now more important than ever, as coffee prices hit an all-time low. Most coffee is grown on small family farms as the family's sole source of income. When the supply is too high, as it has been this year, the farmers earn almost nothing for their crops.

Equal Exchange is a worker-owned coffee cooperative that was the first U.S. company to adopt international fair trade standards. The company's experiences demonstrate a common problem facing all fair trade organizations: raising capital. "It will always be a struggle to communicate to our clients and consumers that we are a rare hybrid -- a for-profit social change organization," says Rodney North, the organization's information officer. And because the organization cannot offer a high return or control to investors, its staff must seek out investment from people who share their values.

Fairly traded coffee got a boost last year when coffee giant Starbucks started selling the product at 2,300 stores and on the Internet. Peet's Coffee and Tea, another national coffee chain, also started marketing fairly traded coffee. The coffee packages carry a TransFair USA seal of certification, a guarantee that the coffee's farmers received a fair price. TransFair is the only U.S. third-party certifier of fair trade products.

Today's non-fair trade coffee market pays farmers about 25 to 30 cents per pound, says Nina Luttinger, communications manager for TransFair. The internationally recognized standard fair trade prices for coffee are $1.41 per pound for organic-grown coffee and $1.26 per pound for non-organic. In the non-fair trade coffee business, a chain of middlemen between growers and consumers drive prices up by the time the products make it to store shelves. Fair trade organizations can pay farmers more because they skip the middlemen, Luttinger says. The coffee goes straight from the farms to the roaster -- from a small family farm in Chiapas, for example, to Starbucks.

The TransFair certification seal gives the coffee an all-important brand and gains the public's trust, Luttinger says. "More and more people want a third-party label to be a fair trade guarantee," she says. "There's lots of cynicism about corporate claims."

Starbucks' move, Luttinger says, was an important step forward in making fair trade items mainstream products. Fairly traded coffees generally sell for the same price as gourmet coffees, a trend that fits well with the niche market most likely to buy a fairly traded item: educated, socially conscious, and willing to pay a little more to support an important cause. More than 100 companies sell coffee bearing the TransFair seal. The organization also certifies fairly traded tea, and will soon do the same with chocolate, a major slavery-driven industry according to Anti-Slavery International.

Outside the realm of food, however, there is no certification system for fairly traded products, and companies and nonprofit organizations struggle for success. Most of these companies are small craft stores and wholesalers that depend on boutiques and fairs to sell their products. Usually the managers have little or no experience running a business, and many fail within a few years. Luttinger's store, Fair Trade Zone, closed after two years because she could not make large enough orders to keep shipping costs manageable. Luttinger said she was passionate about the ideology behind her business, but was not an aggressive salesperson.

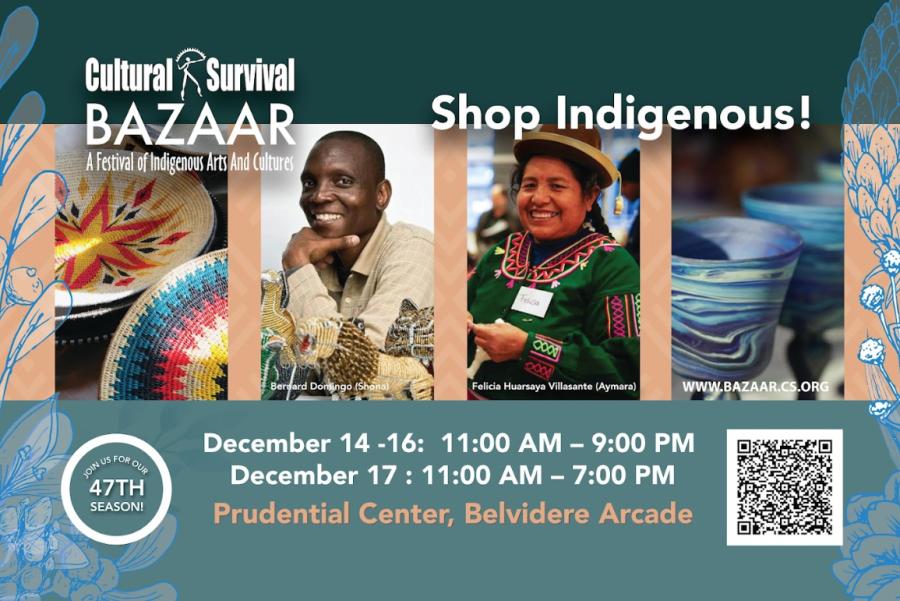

Most businesses like Luttinger's work with artisan cooperatives that set the prices for their products. Fair traders say one asset of the craft business is that it helps families, especially indigenous families, keep their native arts alive. But Luttinger says that crafts are not high-demand items. To go mainstream, fair trade must focus on products like sneakers and jeans, she says.

Ten Thousand Villages, a national chain of nonprofit fair trade craft stores, has had unusual financial success. In business for 53 years, it now operates more than 200 stores in the United States and Canada and is the largest U.S. fair trade organization. One of the company's strengths is its ability to tailor its crafts to the North American market. After locating artisans and cooperatives, market analysts at the organization's headquarters determine the types and quantities of crafts that would sell. The analysts consult the artisans, who decide whether they are able and willing to make the items.

Paul Myers, executive director of Ten Thousand Villages, admits the organization has struggled. In a spring 2000 article in Networks, the newsletter of the Fair Trade Federation, Myers argues that fair trade organizations must make profits to maintain a sustainable operation for their artisans. He says a healthy fair trader should make a three percent profit each year to keep up with inflation. If the company wants to grow, its profit must be five or six percent per year. In the mid-1990s, Ten Thousand Villages made no profit, Myers notes. In 1999, it just missed matching inflation with a profit of 2.5 percent.

But to maintain these profit margins, Ten Thousand Villages must use a business practice unheard of in the normal market-place: All of the organization's store clerks are volunteers. It is unlikely other fair trade organizations will be able to duplicate this model, and the industry continues to search for one that will work for everyone.

Luttinger knows the fair trade industry's most immediate key to success is its ability to stir public interest. She said she has seen a groundswell of consumer interest in finding out how products are made and learning about the lives of the producers. Starbucks began stocking fair trade coffee partly because customers asked for it, she said.

"People would care if they knew it was an issue," Luttinger says. "Let them know most Third World farmers aren't making a decent price and tell them there's an alternative."

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.