The following are excerpts from interviews conducted by Cultural Survival’s staff for Indigenous Rights Radio coverage at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland.

They Are Starting to Listen to Us

Andrea Carmen (Yaqui), Executive Director, International Indian Treaty Council

Indigenous Peoples have had prophecies and stories since time immemorial about what would happen if humans disrespected the natural world and ignored that responsibility to take care of it. The actions of corporations and governments and the addiction of the global community to fossil fuels directly contributed to what everyone, including Indigenous Peoples, recognize as a threat to our food sovereignty, ways of life, and our very survival. I worked with the formation of the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change in 2008, which really became strong in 2015 and has functioned ever since as a global voice for Indigenous Peoples.

We have a responsibility to be here at the United Nations and try to influence the decisions that are being made and defend our rights. In 2015 at COP21 in Paris, we were very active with over 200 Indigenous Peoples participating and getting the rights of Indigenous Peoples recognized in a legally binding international instrument for the first time. It’s in the preamble, which in international treaty law sets the tone and governs the implementation of all of the rest of the provisions. It was really important for us that the Paris Agreement implemented paragraph 135, recognizing the importance of supporting the practices and the key contributions of the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples and creating a platform for the exchange of best practices and innovative programs.

Now, they’re talking “nature-based solutions.” They think Indigenous Peoples are going to get on that green economy bandwagon. But Indigenous people didn’t create any of those terminologies, nor do they reflect our traditional worldviews and practices. They’re promoting things like carbon trading and forest offsets and calling them nature-based solutions, but we’re stepping back from that and staying true to our ways of knowing and what we understand from our millennia of ancestral knowledge and practices, like seed trading, water-saving, and bringing back traditional methods.

A pledge for funding Indigenous Peoples is an advancement and commitment. But there are things that have not really been clarified. Will this funding be advised and managed by Indigenous Peoples ourselves to develop the criteria and the procedures? And what will be entailed in actually getting this funding to Indigenous Peoples on the ground who are working on innovative programs and projects for adaptation and protection of our Traditional Knowledge systems? The caucus has always been strong on the point that this funding has to be provided to Indigenous people from all regions. One of our Māori Elders said, “I see they divide us according to who we were colonized by.” It’s important that our contributions be recognized universally. Funding needs to be made available directly to Indigenous Peoples, not through the States or any other intermediaries.

After the Paris Agreement was affirmed by the vast majority of countries in the world, we had more than three years of consultations with States in various regions to talk about the creation of the Local Communities and Indigenous People’s Platform. A strong demand that Indigenous people had for the creation of this platform was equal participation between Indigenous Peoples and States. It created a very revolutionary process in the UN system. It is ironic that it happened in Paris, because this was one of the worst conferences for participation—we weren’t even allowed in the rooms of negotiation for the Paris Agreement. But now we have a constituted body here at COP26 made up of half Indigenous representatives chosen directly by the Indigenous regions. We are true representatives, not independent experts. This is the first time that we have had direct representation in any UN body. I was selected by the Indigenous Peoples of North America, Canada, and the United States Tribal governments, treaty councils, and grassroots organizations, the gamut of us working together by consensus. I was nominated in 2019 to be the first member serving for a three-year term on the Facilitative Working Group, which was put in place at COP24. They are starting to listen to us.

If We Don’t Reduce Emissions, We’ve Made No Progress

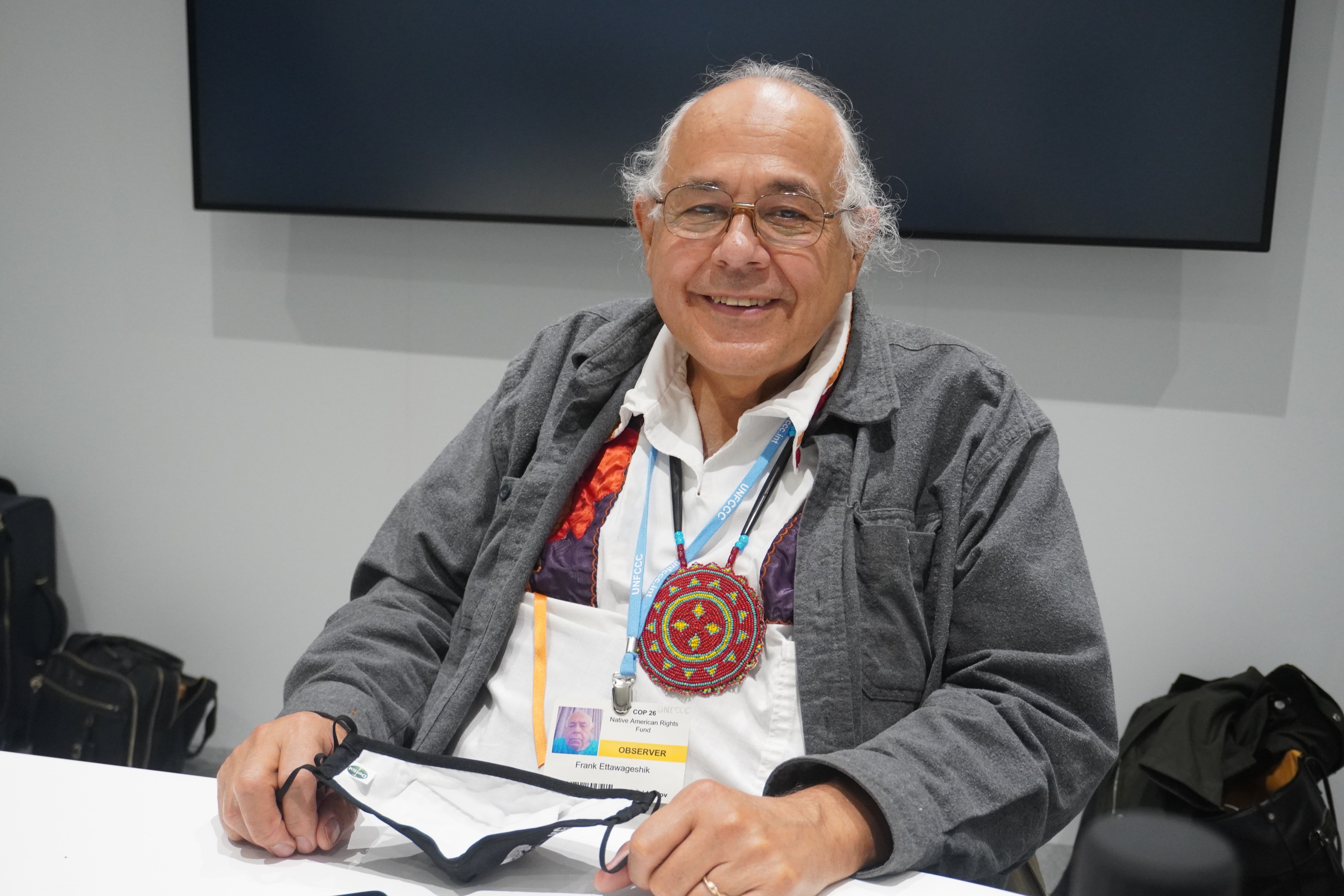

Frank Ettawageshik (Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians), Executive Director of the United Tribes of Michigan and President of the Association on American Indian Affairs

We are part of a group called the Human Rights and Climate Change Constituency, which is a confederation of many organizations that are working together, including women’s organizations, unions, [2SLBGTQIA] groups, and environmental groups, to lobby for human rights issues. In the Paris Accord, we got Traditional Knowledge of Indigenous Peoples acknowledged, which was important. We argued that Traditional Knowledge is fundamental to the preservation of humanity; not just a catalog of information, but a way of life, a way of knowing the world. As a human culture, we did not show respect to the rest of the world. We didn’t show respect to each other. We were not showing respect to the water or to the trees or the other beings on Earth. By disrespecting and getting out of harmony, we’re now paying a price as a human society. Within the fundamental teachings of Indigenous Peoples, principle amongst them is respect for the natural world. All the solutions that they’re talking about, you can get lost in the data. But fundamentally Indigenous Peoples are trying to share their philosophy and values with the rest of the world so that they will regain respect for the natural world and thus help create harmony and balance. Climate change is a strong example.

Indigenous Nations around the world have joined with the 1.5 to Stay Alive Coalition, a group of coastal and island nations and allies, Indigenous Peoples, and other people who believe that 1.5°C or below (of temperature rise above the pre-industrial levels before we were burning all the fossil fuels) is where we have to be. We couldn’t really go for a higher goal, whereas the U.S. and China had agreed on 2°C coming into the COP21 in Paris. But we were able to get that modified with this large coalition of whom the Indigenous people were part.

When we were working on the Paris Agreement, there’s a thing called the Paris rulebook that lays out how this process is going to work. All of the articles have been adopted except for Article 6, which is the accounting mechanism that has to do with market and nonmarket solutions on how this will be integrated. It fundamentally says that anything under Article 6 is supposed to be measured by whether it truly causes a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions or not. Fundamentally, if we don’t reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we can have all these fancy agreements, we can spend lots of money and have money flowing all over the place, but if in the end we don’t actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions, then we’ve made no progress.

We have to do a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, and eventually we have to phase out the use of fossil fuels. These mechanisms are ways to try to help figure out how we’re going to do that and how we can account for that. That’s how countries are going to be able to develop the data that they can then use to show how ambitious they’re being with their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The Paris Accord works because the countries develop a Nationally Determined Contribution. Arguably, all of those NDCs, when they’re put together, will be an aggregate number that will show that we will be lowering greenhouse gas emissions to the point where we keep it to 1.5°C or below. That’s the goal. The NDCs have to be ambitious enough, and that ambition is going to be demonstrated by the way they are developed. Article 6 is integral to the way they’re going to calculate and what they get credit for in the NDC.

It’s Up to Us to Define a Just Transition

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz (Igorot), Former UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The Just Transition basically is saying that we should stop doing business as usual. We should cut back on fossil fuel emissions, the extraction of coal, and the use of gas for energy sources, and we should shift towards renewable energy sources in relation to our production and consumption systems. Industrial agriculture is emitting emissions in very significant ways. Agriculture has to be done in a different way, like Indigenous Peoples are doing. They call it regenerative agriculture, but actually Indigenous Peoples have been doing this since time immemorial. We have different ways of managing the soil, shifting cultivation. The Just Transition covers the breadth of how climate change is being exacerbated. Corporate control is a very big factor in this. There should be more democratization in how resources are extracted, produced, and also consumed.

A Just Transition to a green economy can mean a lot of things; it’s up to us to define it. We should ensure that the human rights of Indigenous Peoples are respected. Indigenous people should strengthen their capacity to govern themselves, to be more self-determining and sovereign and able to shape their communities. Indigenous Peoples’ actions are the ones that will contribute to solving the climate change crisis. So Indigenous Peoples should be empowered. They should ensure that there is better gender equality and that the youth are included in their processes so that kind of leadership will be transmitted to future generations—Traditional Knowledge, Indigenous justice systems, education systems, and health systems. They have to be the ones to define and design the society that they would like to leave behind for future generations.

We Can’t Solve This Crisis Without Indigenous Peoples

Fawn Sharp (Quinault), Vice President of Quinault Indian Nation, President of the National Congress of American Indians

Climate change is not only impacting our fisheries resource directly, which is core to who we are, our identity, and our traditional foods, but the glaciers that feed the Quinault River have disappeared. We’re currently under a state of national emergency due to sea level rise and the ocean is threatening to take out the only access road to our village. The place where my ancestors signed a treaty with the United States is underwater at this point, and the only access road to our village is threatened due to a landslide. I’ve personally witnessed the disappearance of our glaciers in the Olympic Mountains. I’ve had to declare four national states of emergency, and just five months ago, we experienced 111°F temperature, the hottest temperature ever recorded. Our fish were being cooked alive with visible heat lesions. Clams were being baked in the open beaches as the tides receded. Our conifer trees were scorched brown. All across Indian country every region is affected by climate change, from Tribal leaders in Alaska to Tribal leaders in California who are facing megafires and Tribes in the Gulf that are facing hurricanes and tornadoes.

At COP26, we’ve had direct engagement with the Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry. He addressed the National Congress of American Indians, and his words were promising in that he acknowledged that the future health of the planet, as well as humanity, is inextricably tied to ensuring that the voices of Indigenous Peoples are not only heard, but that we’re at the table. That signaled to us that the United States was not only open but wanting to elevate our voices, because they recognize that we offer timeless solutions. We can’t solve this crisis without Indigenous Peoples. We must be active participants. We must not only have a seat at the table, but our voices and the solutions that we offer must be heard. We also are advancing Free, Prior and Informed Consent domestically and internationally. It’s critically important for Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples to have a decisive say over our lands, territories, and resources. We’re pressing countries about implementing these commitments that were adopted in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Biden administration’s commitment not only to Tribal Nations, but acknowledgment of our matriarchal leadership, is exemplary. When Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) was appointed as the Secretary of Interior, it was the first time a Native American was appointed to a cabinet level position—and a Native woman. She brings a view of not only Indigenous Knowledge, but as a woman, she’s inspiring an entire generation of women leaders. I personally witnessed our young girls, our future leaders, look at her with awe and know that our women have a rightful place. When we’re in positions of leadership like that, we can make transformative changes and incredible advancements in a relatively short period of time. It’s an exciting time, and we are going to continue to blaze those trails and open up opportunities for the next generation of

women leaders.

Calling for Urgent Action to Address the Devastating Impacts of Climate Change

Graeme Reed (Anishinaabe), Co-chair of the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change

The Indigenous Peoples’ Constituency is one of nine constituencies originating from the major groups in the sustainable development conversation. We were created as a constituency in 2000, then self-organized into the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC) in 2008. Our main role is supporting Indigenous Peoples who participate in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. We work to develop collective solidarity and positions in advocacy and lobbying that contribute to the advancement of our self-determination, the safeguarding of our rights, meaningful and thoughtful consideration of our knowledge systems, our full and effective participation as Nations, and finally, the ongoing call for urgent and transformative action to address the devastating impacts of climate change on our lands, waters, and territories.

We opened our session as usual with a preparatory caucus meeting just before the COP26 formally opened. That space is intended to support and coordinate Indigenous Peoples attending and to build relationships. We also held daily coordination meetings to respond to the various activities of each day. In Scotland, we organized the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change Pavilion, the first Pavilion hosted in the Blue Zone (UN organized space). We had around 70 events over the course of the 2 weeks. It was all live streamed and saved on our IIPFCC Facebook page.

We were able to get an agreement at COP24 for the creation of a newly constituted body called the Facilitated Working Group with seven Indigenous representatives from seven UN sociocultural regions. At COP26, we had the first-ever annual Knowledge Keepers Gathering with 28 knowledge keepers from those 7 sociocultural regions, and we had our own meeting that allowed us to create our own space. This is the first time that we’ve had a meeting within the parameters of the Blue Zone that explicitly asked States to stay out. That’s an indication of our growing ability to create space for Indigenous Peoples within these systems.

We also have advocacy objectives. One of those was Article 6 and the implementation of carbon market mechanisms. The caucus has been extremely effective in communicating the importance of the protection of human rights and the rights of Indigenous Peoples and making sure that that language is captured within Article 6. Other successful outcomes were the creation of an independent grievance mechanism and the adoption of the second three-year work plan of the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples’ Platform, which was co-constructed on a consensus basis by the Facilitative Working Group, a group made up of equal numbers of Indigenous Peoples and States. We also landed a decision on the Climate Technology Center and Networks Advisory Body. Indigenous Peoples have been advocating to have one seat, even if one seat is insufficient, to represent Indigenous Knowledge, science, and perspective on the climate technology network.

COP27 will be held in Cairo, Egypt, on November 7–18, 2022. IPFCC will be advocating for human rights, Indigenous Knowledge participation, concrete action, and speaking out against the massive injustices faced by Indigenous people including the ongoing criminalization, dispossession, and assassination of our lands and water defenders.

Listen to 25+ interviews with Indigenous leaders speaking about climate change impacts and solutions at COP26: rights.cs.org/cop26.