In the unlikely land of Ladakh, where verdant hamlets bloom in the grip of the Himalayas and monks ride motorcycles, survival is an art form. And Ladakhis proudly exhibit their mastery of it.

As in most Ladakhi homes, a massive iron furnace presides over Angmo Sutu’s kitchen. The stove is respected like some unusually dignified human guest; Angmo and her family never show it the soles of their feet, and the knee-high dining tables are arranged so that nobody need turn their back on it during meals. Yet there is nothing self-effacing about this behavior, no worship implied. It is just an instinctive display of respect for the black behemoth that enables the Sutu family to survive winters as cold as 5º F—and, by extension, a homage to the human ingenuity and labor that produced such a life-saving device.

Behind the stove, an entire wall gleams with cookware, burnished and stacked on shelves or behind glass cabinets. Nothing is hidden away in cupboards or drawers. Along the top of the wall sit jars of spices, empty cans of Lactogen milk substitute, and hand-painted wooden flour canisters. In the center of the display loom enormous hand-hewn pots and pans, flanked by towers of porcelain teacups. On the lowest level, next to the eating area, brightly colored thermoses are lined up in order of height. Somewhere near the flour canisters and Lactogen, the Dalai Lama beams down from a frame hung with amulets. A magnificent aesthetic effect is achieved in the display of instruments with which Ladakhis eke life out of their environment. In a Ladakhi kitchen, in a Ladakhi life, all the bothersome parts of subsistence—scrubbing pots, heating water, yanking food out of the ground—are one with art, with faith, and with the transcendent moments in life that complement the discomforts.

The Sutu family lives in Likir, a village 30 miles northwest of Ladakh’s capital city, Leh (but a bumpy three hours away by bus or taxi). Likir is mentioned in most guidebooks on Ladakh, and even has a wikipedia.org entry for being the site of an 11th-century gompa, or monastery. Today, the gompa is distinguished by its leader, the Dalai Lama’s younger brother, and by a 30-foot statue of the Buddha. It crowns the village, which is draped over a hillside split by a steep gorge. A tributary of the Indus River plunges raucously through this canyon and goes on to trace a line of villages across central Ladakh.

From a distance, it is risibly clear how totally the residents of Likir have defied their surroundings. The town is a bright green carpet in a valley of brown boulders, a neat staircase of terraced fields scalloped out of rugged mountains. In the garden of the Sutu home, scarlet poppies and giant marigolds bloom freely, unaware of how improbable their existence is.

Watching Angmo Sutu for a day explains volumes about the upkeep of this vision. The 32-year-old woman works nearly ceaselessly, managing her own household for much of the day but continuing to wash dishes or knead bread even while visiting friends. Indeed, it is customary for Ladakhi women to call upon each other for a cup of tea and splash of gossip, then spend several companionable hours weeding the hostess’s garden. The more I observed Angmo going about her daily business, the more apparent it became that nearly everything she does is directly or indirectly a form of food preparation: pulling up weeds to feed her cows, flooding the vegetable garden with bitter almond paste to rid it of grubs, irrigating her wheat and mustard fields, pounding and drying cow dung to fuel her stove, churning milk into curd, making salty pink tea with an ancient plunging apparatus that resembles a quiver.

Angmo has two children: twelve-year-old Tsering, a kind and quiet boy at home but an established member of the local rat pack, and nine-year-old Stanzin, whose shrieks and giggles and periodic tantrums must be familiar to associates of nine-year-old girls worldwide. Their shy, warmhearted father, Jorgas, works as an ornamental carpenter, dividing his summer between assignments in Leh and Likir. Jorgas’s parents, Rigzin and Dolma, live in a separate house on the property. It’s a mark of how wealthy and influential the family is that Angmo and Jorgas can afford to live apart from his parents. When they married 13 years ago, Rigzin called on all his friends, and spent a great deal of money, to build their house. Lamas, friends from faraway villages, even Dolma’s women friends all came together to help construct the building, whitewashed, squarish, and flat-roofed in traditional Ladakhi style. Jorgas’s brother Sonam, a painter and devilish mimic, also lives with the family, and Stanzin and Tsering call both men aba-le, or “father,” treating each brother with equal affection. Sonam, in fact, spends more of the summer in the house than his brother. Jorgas’ time in Leh appears to weigh on him a great deal: one night he returned from 10 days in the city and seemed to have forgotten how to interact with his family. His brother, wife, and children crowded around the table at dinner that night while he sat across the room with his plate, looking on sadly.

The final member of the household is invariably referred to only as Abi-chomo, or “grandmother-nun.” A tiny, wizened creature, she is an impressive 74 years old (and weighs nearly as many pounds, according to a year-old medical record). She wears the maroon robes and yellow cap of the Ge-lugs-pa Buddhist order, and is usually accompanied by prayer beads and the faint cheeping of her prayer wheel as she swings it about. She accessorizes her outfit with a pair of faded rubber Spiderman sandals she wears outside. Each Ladakhi appears to own a pair; they are undeniably well suited to Ladakhi farm work. Some days, even Abi-chomo can be found in the field, weeding or irrigating, moving slowly through the grass like a small red shadow. In the mornings she sits by the kitchen window, warming up in the sunlight, looking as sweet and delicate as a baby bird.

Ladakh is the northernmost territory in India, scattered over concentric mountain ranges: the Stok, Zanskar, and Himalaya to the south, and the Ladakh and Karakoram to the north. Just six inches of rain fall on these parched peaks each year (although recent climate change has resulted in increasingly unpredictable precipitation), so Ladakhis find their water in occasional rivers of mountain run-off and a few underground springs.

But bringing enough water to her fields and family is more than a chore for Angmo. It is a refined skill and an opportunity to socialize with other women, her role in an elaborate community performance. She spends hours marching swiftly through the labyrinth of water channels that lace Likir, swaggering ever so slightly, a spade slung authoritatively over her shoulder. Some mysterious, unspoken agreement determines when each family may direct the water flow to their property; Angmo simply diverts the flow to her house on washing days, or to her fields when it is time to irrigate, sometimes sending her children if the task is simple.

The method by which water is disseminated through Likir is a metaphor for the entire village. It bubbles up from springs and river channels and permeates the village through an intricate network of channels that bring water by every house. The direction of its flow can be changed at various carefully placed forks and bends by the construction and demolition of walls made of rocks, old clothing, and dirt. Any Ladakhi strong enough to lift a rock can build these walls quickly and effectively. A similar process is employed in the wheat and mustard fields at smaller scale: a stream is diverted around the edge of each terraced platform, starting with the highest and trickling down to the lower ones. Since the fields are divided into lanes that run perpendicular to the field’s edge, stopping up the stream at certain points in its path sends the water rushing off into each lane of flowers or silvery-green wheat, so neatly that the bridges of hard dirt separating each lane remain completely dry on top.

It’s a remarkably efficient system. Gravity and careful planting patterns do most of the work, but all the control over where the water goes, and how much, is left to humans. Like so much of Ladakhi culture, it is an ingenious and creative response to the unfriendly environment.

The scarcity of water, and the improbability of any lasting human settlement in such arid environs, is starkly obvious at the outer limit of each village. All vegetation vanishes abruptly, replaced by a rocky desert of crumbling reddish cliffs and swirled sandy rises, punctuated by chalky Buddhist stupas.

Carved images in some rocks suggest that humans were in the area as early as Neolithic times, but the first known inhabitants were Indo-Aryan herdsmen from the West and Mongolian nomads from Tibet, who drove their livestock up Ladakh’s precarious passes in search of fresh pastures. These initial settlers may have arrived as early as 500 B.C.E., and practiced the animistic Bon religion. But by the 1st century B.C.E., Buddhism had arrived in Ladakh to stay. The land was subject to periodic invasions launched over the next two millennia by Kashmir, China, and Tibet. The latter triumphed briefly, and some of its own former royalty went on to found the sovereign kingdom of Ladakh in the 10th century C.E.

Ladakh is most often described in terms of this Tibetan influence, which is visible in the Ladakhi language, folk art, religion, medicinal traditions, and architecture. Yet Ladakhis have always been slightly removed from actual Tibetan society. Historically, “they were the country bumpkins of Tibet”: far from Lhasa, the hub of Tibetan culture, and lacking any real system of socioeconomic stratification.

While folding clean laundry with friends one day, Angmo was clearly in a mischievous mood. She first pretended to be a clothing-seller in Leh, holding up clothes and calling out “Ten each! Ten each!” in Urdu. Then she ran out of the room to dress up in her husband’s clothes and exaggeratedly impersonate him, all to gales of laughter and goading. There is no scheduled moment or place for laughter and entertainment in traditional Ladakhi culture, no equivalent of “leisure time.” Instead, jokes and games, or yanspas, generally occur spontaneously. The most laughter, in fact, seems to surround situations that have the potential to be deeply painful. I once asked Jorgas’ mother, Dolma, about her siblings, unaware that all had passed away. She began listing the Ladakhi words for older brother, younger brother, older sister, etc., closing her eyes and sticking her tongue out after each one with a small groan: “Acho-le . . . unhh. Nono-le . . . unhh. Ache-le . . . unhh.” She couldn’t finish, however, before her voice cascaded into uncontrollable giggles, and everyone around her practically fell over laughing.

On another occasion, Angmo was ordering Stanzin to blow her nose, threatening to send her daughter off to marry an American husband if she didn’t obey. Stanzin began hurling things at her mother, utterly distraught, before running out of the room in tears. Angmo sat where she was, rocking with laughter; for days later, the memory of it was enough to set her off again. While a daughter in an unhappy marriage or the death of a relative would upset a Ladakhi as much as anyone, my shock at the litany of Dolma’s deceased siblings and Stanzin’s outrage at the prospect of marrying an American amused them endlessly. Perhaps they were laughing at the absurdity of human attachments, the illusions of permanence and control over their own fate. If, as Buddhism teaches, recognizing those illusions is key to true contentment, the Ladakhis are indeed a very contented people.

Of course, Ladakh is not immune to discord. As Angmo, her friend, and I sat down to lunch one afternoon, the two Ladakhi women began listening intently to something outside, discerning the words being exchanged before I could even hear a distinct conversation. “It is an argument,” Angmo informed me matter-of-factly after a short while. “Two neighbors are fighting about whose house the river goes to today.” Her tone suggested that disputes over the water supply are fairly common, yet still rare enough to warrant rapt attention.

Curious to know whether harmony extended to the family level, I asked Angmo one day while we made bread together to describe her wedding to Jorgas. I inquired if they were friends before their marriage. “We didn’t know each other at all,” Angmo answered, surprised that I had even asked. Most Ladakhi marriages are still arranged by the fathers of the young people (and “young” is the operative word—some girls are still married off at the tender age of 12). Ladakhis used to practice polyandry quite regularly, until it was made illegal in the 1940s. A few women still take more than one husband (usually brothers) but mostly in parts of Ladakh north of Likir. When Angmo married Jorgas, their fathers first held a formal consultation. Since Jorgas’ family was far wealthier, Angmo’s father had to pay a sizable dowry. Angmo says she was very sad to have to leave her family and move in with a stranger, but today she is happy with her situation—happy enough to be planning the same fate for her daughter. Of course, not all arranged marriages turn out so well; divorce has always been fairly common in Ladakh.

The largest social disturbances in Ladakh’s history have come from outside its borders. In the centuries following the country’s founding, Muslim armies from Baltistan and then Indian Mughal troops weakened Ladakh to the point where, in 1846, it was formally incorporated into the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Though it has maintained that status ever since, Ladakh has gleaned impressive degrees of autonomy in the past 15 years. In 1995, a community-based, democratic governing system called the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council was set up, and its leaders granted the right to make all decisions affecting Ladakhis except control of law and order, which remained with the Kashmiri government. The decentralized structure allows the traditional Ladakhi governing bodies—councils of elders in each village—to maintain considerable power.

But Ladakhis are still overwhelmingly eager for one more degree of independence at the national level: they want to split from Kashmir altogether and become an Indian Union Territory of their own. It’s not just about the label. “We think Kashmir wants to take us over, wants to make Ladakhis Muslim,” says Ringchen Gaph-Chow, a young woman who helps her husband manage a guesthouse in Likir. Although the Indian government has proved unreceptive to these concerns so far, Ladakhis are tenacious in their quest for greater independence. It may be just a matter of time before this next goal is achieved. Even as Ladakh marches toward political autonomy, however, a more insidious vulnerability is apparent in the population.

After visiting relatives in a nearby village to fetch six huge bales of hay for her own cows, Angmo rolled each washing-machine-sized bundle down to the bus stop and awaited the vehicle, confident that it would be able to transport them back to her own village (it could not, having barely enough room and horsepower for its passengers). Power lines hang lazily through fields and gardens in Likir, protected by just a thin rubber casing; in the Sutu garden, one is slung at the perfect height for a clothes-line and is often accordingly draped with wet clothing. Everyone, even wise Abi-chomo, casts candy wrappers onto the ground as though assuming they will disappear like compostable food. Sonam spends most of his days painting in enclosed rooms with leaded paint. One evening, I saw Stanzin slide a plastic shopping bag over her head and prance about the kitchen to the great amusement of her mother. These behaviors were not just major lapses in common sense; they bespeak the momentous changes that Ladakh has been undergoing since Angmo was born.

Since Ladakh was opened to tourism in 1974, a rapid influx of cash and Western cultural influences has transformed the entire region. While these changes are most evident in Leh, they are also plainly visible in small villages like Likir. Most families now own a satellite television or radio, and men and children invariably sport Western clothing. Along with those innocuous acquisitions have come Western agricultural practices like heavy use of pesticides, cash-crop production, and processed foods, all of which have serious impacts on Ladakhi health, economics, and society. In an attempt to temper the effects of cultural transition, anthropologist Helena Norberg-Hodge has launched the Ladakh Project, which attacks the problem from both ends. It sends volunteers like me from the West to live and work with a rural Ladakhi family for one month. The project also discourages Ladakhis from using chemical fertilizers or pesticides, buying foreign foods at subsidized prices, or farming just one crop in order to sell it. It also sponsors various renewable-energy initiatives, created the Women’s Alliance of Ladakh, and sends Ladakhi community leaders on “reality tours” to cities in the industrialized world so they can see what life there is really like. Central to Norberg-Hodge’s work is the belief that globalization is the enemy. “That’s what’s created the gap between rich and poor and so much ecological destruction,” she says. But its most pernicious effects on Ladakh, Norberg-Hodge thinks, are the cash-cropping and mono-agricultural practices.

Tsering and Stanzin’s favorite food is white rice—an odd choice, considering it is not grown anywhere near Likir—packaged along with generous amounts of grit and small stones. The oddest recent addition to the Sutu pantry, though, might be Lactogen milk substitute, a saccharine white powder that tastes like sand compared to the rich, fragrant flavor of milk from Ladakhi dzomos (a hybrid between cow and yak). Animal husbandry has declined greatly in recent years, though, as fewer members from each family stay in the village to take care of the farm. The supply of milk from the remaining dzomos might not be sufficient anymore. Land is becoming scarce, as well. The borders of each village have not expanded, but more and more young couples (like Jorgas and Angmo) can now afford to move out of their parents’ house and build their own, filling up land and forcing the parents to divide up their family fields. Nowadays, almost every Ladakhi family supplements whatever they farm themselves with food bought in Leh.

The new economy also gives Ladakhis access to some healthy foods, like fruit and vegetables that they don’t have the desire or ability to cultivate themselves. Nearly every Ladakhi crop is grown in summer, but with winter in mind. Farmers expend most energy on harvesting fruits and vegetables that can be dried and stored for nine months. The traditional Ladakhi diet is based on bread and various forms of partially cooked or uncooked dough, with occasional turnips, peas, potatoes, cabbage, and curd to alleviate the monotony. Apples, apricots, and the sweet almond-like kernels found in apricot seeds are dried and enjoyed all year long. These foods keep Ladakhis strong and energetic, but are most likely responsible for their short life expectancy. Ringzen Lamo, a traditional doctor, or amchi, believes Ladakhis die earlier than people living in industrialized countries largely because “in winter, they don’t have a very good diet.”

Most Ladakhis die before their hair turns white, and often from digestive complications. Six years ago, a stomach-related illness killed the brother of Tsering Spon, a young painter from Likir. He has raised his nephew ever since, in addition to his own children. The parents of 74-year-old Abi-chomo died when she was young, both from stomach ailments. And Angmo’s mother died of a stomach problem when Angmo was 12 and her youngest sister was still nursing. Her father was in the army, so responsibility for parenting her younger siblings fell to Angmo, and she was forced to drop out of school: something she has always deeply regretted.

“Losing my mother was very, very difficult,” says Angmo, and indeed it is evident how highly mothers are valued in every aspect of Ladakhi culture. Fathers rarely mete out punishment or exuberant affection the way mothers do. When frightened, in pain, or even easing themselves up from a stiff position, Ladakhis invariably give a sigh of “Ama-le!” (Mother!). Yet children are raised not only by their own mother but also by a cadre of her female friends.

With few manufactured toys or external sources of stimulation, young children play and learn almost exclusively through imitating others. Tactile games are also very popular. Everyone in the Sutu family can juggle, the village children all know cat’s cradle, and several variations on the digit-pulling game “This little piggy” exist; one chant is simply for remembering the Ladakhi names for the fingers.

As might be expected, traditional Ladakhi culture has no written games. I tried to teach Angmo, Dolma, and Tsering tic-tac-toe one day, but only Tsering could understand the point—his mother and grandmother laughed for a while at my stumbling explanation of it, but could not comprehend or muster much interest in the game itself. Most Ladakhi women over 30 years old do not speak English or Urdu, and can write very little even in bodyit, the classical Tibetan script that the Ladakhi language shares. Angmo wrote her name for me in bodyit one night: a torturous 10 minutes of her struggling to remember the characters and soliciting help from her children, broken by many dismayed sighs and smiles and burying her head in her hands. Dolma, determined to match her, announced that she could write her name in English, and after another few minutes of careful inscription, proudly presented me with a paper upon which she had written “TDDLMA”—the vestige of a long-ago lesson.

Sometimes, Angmo comes over to her children as they sit writing their homework in English and Urdu, idly polishing a plate and looking over their shoulders with a mixture of curiosity and longing. It is a world over which she has none of her usual mastery, nothing to teach her children. The local public school, as it turns out, has little to teach them, either. The English education they receive is particularly atrocious, focused solely on memorization and recitation. Their workbooks laud a modern, industrialized lifestyle and disparage the “olden times, when people rode animals instead of driving cars.” In the past few years, some groups have tried to improve public education in Ladakh and relate it more to the lives of Ladakhi students. One of Stanzin’s textbooks is published by Operation New Hope, an initiative that aims to “produce Ladakhi versions of early primary teaching materials in order to make them more relevant and meaningful to Ladakhi children.” The book does ask questions relating to the culture and natural history of Ladakh, but this description of Operation New Hope and the entire workbook in which it was found were in English.

On the night Jorgas returned from Leh, Stanzin began reciting the times tables in English at barely intelligible speed, trying to impress him. But when I asked her one of the same multiplication problems—eight times eight—in Ladakhi, she started marking eight little sets of eight dots on a piece of paper, then gave up halfway through and started drawing instead. None of this was apparent to Angmo, however, who seemed, as I’d never seen her before, somewhat ashamed of her own lack of education against her children’s ability to parrot off English phrases from their textbooks. This is particularly heartbreaking because Ladakhis so rarely exhibit shame.

A high-pitched “Mentok ldumrey nangs-la, tsapik skyoda-aa-aaat,” often issues from the Sutu kitchen in the evening. Tsering sings along to women warbling Ladakhi folksongs on the family’s radio just like his sister, spontaneously expressing his delight in the melody without worrying what others will think. Gender roles are very hard to distinguish in the communal, candid culture of Ladakh. At the house of one of Angmo’s friends, I saw an 11-year-old boy watching his sister apply rosy pink nail polish; as soon as she was done, he snatched up the vial and decorated his own nails. And adults likewise display little affectation. On the first day I met Dolma, sitting around Angmo’s table together, she grew drowsy and lay down, resting her head on my knee. Neither is it unusual for men to sit by each other with arms around each other’s shoulders, or walk down the road with hands on each other’s backs.

Buddhism is very much present in the everyday lives of each Likiri; even Stanzin goes out of her way to keep the village stupas on her right (as one is supposed to pass any Buddhist monument), incorporating the minor detour into her frolics. And pungent smoke weaves through the Sutu house several times a day, as Abi-chomo carries a dish of smoldering fir twigs past each room to “clean bad spirits away.” Angmo and I visited Jorgas’s uncle’s house one day, for what I was told would be a “very big celebration.” A group of lamas prayed, blew long zangstung horns, and built little effigies out of flour, curd, and butter in the next room. We women hid in the kitchen for the whole day so that the monks would have no distractions, while Jorgas’s uncle relayed food into the prayer room. At one point, he brought a saucer of blessed saffron-water back from the lamas. Each person slurped a bit up than slapped some on his or her forehead to protect against headaches.

If this preemptive treatment had not worked, the Sutus would have a choice between an amchi and a small government-run clinic that doles out Western medicine. Dolma showed me a little wound on top of her head one day and said it was from an amchi; I later found out that she had been stabbed there by a golden needle, meant to cure chronic migraines. According to amchi Ringzen Lamo, amchi medicine is 3,500 years old and based on the idea that all ailments are the result of an imbalance of bodily humors and energies: broadly, a “lack of understanding.” The amchi cannot help those with, as Lamo words it, “diseases from a previous life,” and will send a client to a Western doctor if he or she needs immediate treatment or surgery, which amchis do not perform. The most common problems treated by amchis, Lamo says, are rheumatism in the old and indigestion. Angmo had an excruciating headache one day and headed for the clinic because it was free and would provide her with instantaneous relief. Amchi cures can take several weeks to work and, more importantly, cost money.

In just 30 years, Ladakh has acquired a full-fledged cash economy. The Likiri painter Tsering Spon effusively praises the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council for providing Ladakhi villages with free schooling, free medicine, free water, and electricity for just 50 rupees a month, not mentioning that before he was born, every part of Ladakhi life was gratis. Money is behind many of the recent changes in Ladakh. More men are signing up for the army these days, moving to the desolate army bases whose khaki roofs and chain-link fences break up the desert landscape along the road from Likir to Leh. No patriotic impulse drives them, no abstract sense of loyalty to their state. The army pays very well.

The traditional way of life is admired by many Ladakhis, but uneasily. Ringchen Gaph-Chow hopes her eventual children will leave Ladakh when they are grown so that they can earn money. “It’s impossible to keep our traditions and make money,” says Gaph-Chow. “If they could make money in Ladakh then they should stay, but there is little money to earn in Ladakh.” Yet Gaph-Chow prizes money so highly because it allows one to leave Ladakh during the nine-month, brutally cold winter. Clearly, a more wholesale rejection of the traditional Ladakhi lifestyle is burgeoning in this woman. Gaph-Chow herself would, she admits, like to be an airplane stewardess if she and her husband didn’t need to manage his guesthouse and take care of his parents.

Other Ladakhis’ dreams are closer to home. Stanzin would like to be a teacher in the nearby town of Saspul, she confided in me, but—more radically—she does not want to get married or have children. She has no desire to go to India or America, although she does seem fairly susceptible to their cultural sway. When I arrived in the Sutu home, she immediately sought me out to paint my nails. On many evenings, she struts around the kitchen, mock saluting her family and calling out “Hello!” and “Namaste!” (the Hindi greeting). A few days before I left, the Sutu family acquired a television. In those few days, before the television had lost its mysterious novelty, I saw a change in their home. Earlier, Angmo had laughed when I had described how Americans sit glued to their TVs, openmouthed, conversation with other people forgotten. But I saw her display the same behavior as soon as their TV set was installed (although she did often turn to her husband and children in questioning wonder at the sight of an alligator or golf game). Despite the fact that no Ladakhi programming exists farther than 20 miles out of Leh, she and her family sat mesmerized by bizarre Hindi soaps and horror flicks. Those hours in front of the TV were the first times I had seen Angmo truly idle. And tellingly, a day or two after the TV arrived, Stanzin began pestering me to speak Hindi with her instead of Ladakhi. When her cousin visited soon after, bringing her supply of the “Fair and Lovely” skin-whitening cream that so many Ladakhi men and women use nowadays, I noticed Stanzin slip a bottle away to her own room.

Tsering and a friend once showed me a toy that is quite common amongst Ladakhi kids: a four-wheel scooter-type vehicle, made from wires and twigs, with a colorful steering wheel at the top of a long pole. The structure is too fragile to stand on, but Tsering and his friend often pushed it around, swiveling the steering wheel and chasing each other around the Sutu garden. Tsering’s friend saw me looking on and gestured at the toy, joking slightly shamefacedly, “This is a Ladakhi car.”

At this point in his life, Tsering also wants to stay in his home village and become a farmer, as his mother hopes. Angmo, who cannot locate Ladakh on a world map and does not know who George W. Bush is, has no desire to move out of Likir either. “I have to take care of my grandfather,” she says, and “I am not happy in the city.” But this makes mother and son anomalies. Murup, a middle-aged farmer in Likir, explains two common motivations to get out of the village, if only to Leh: “If I stay here, I work and work and work and die; if I go to Leh, get a job, I can relax. And if I want to send my babies to school, university, I need a lot of money.” The first part of Murup’s reasoning is a bit doubtful. Leh is hardly relaxing, its streets peppered with stray animals picking at piles of trash and swiped by careering, honking cars. Finding a job there is similarly stressful; every time a job is posted in Leh, Tsering Spon says, “hundreds of people will line up for an interview.” But Murup’s dream of university for his children is more understandable. A university education is something nearly everyone covets, no matter where they hope to end up afterwards. Most Ladakhi university students attend school in Jammu rather than traveling all the way into India proper, but courses ranging from medieval English literature to hotel management can be taken even at the university in Jammu.

The television may stop conversation, but come nightfall, the Sutu family’s battered old radio inspires them to sing. On nights when the radio is off, they are silent as well, but when it goes on everyone sings along to the lyrical Ladakhi folksongs. Clearly, these new technologies and influences do not suck all Ladakhis into a cult of Western culture, nor are they all inherently destructive. The opportunity to eat fresh vegetables after they can no longer be pulled from the ground is greatly appreciated by Ladakhis who have no choice but to stay in their village all winter. And the chance to earn university tuition for their children excites almost everyone. As more and more Ladakhis buy televisions, furthermore, a Ladakhi-language program about Ladakhi affairs has started up in Leh. The Learning From Ladakh project hopes to use that program to broadcast its message about the importance of retaining culture.

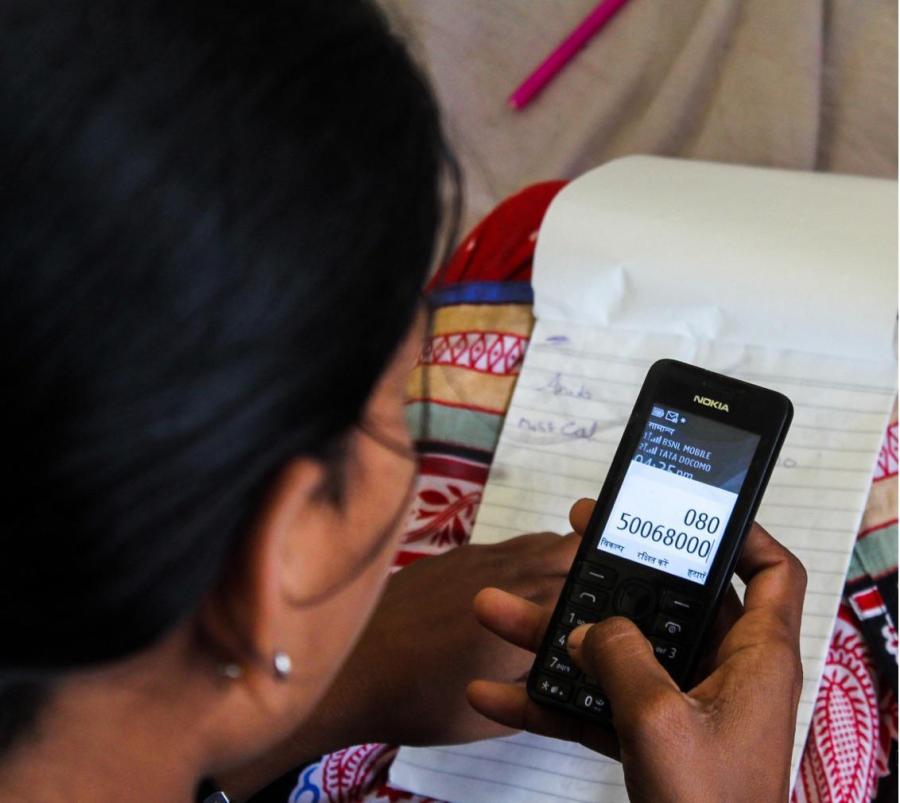

At some level, Ladakhis are actively choosing these modern technologies and incomes for themselves. When I asked Ladakhis why they want more money so badly, the distinction between that cash economy and the traditional way of living becomes more blurred. It now costs more to live a purely traditional Ladakhi lifestyle. Ladakhi gonchas, the heavy, long-sleeved dress-coats that are nowadays worn only by the elderly, are far more expensive than the cotton salwar kameez worn by most Ladakhi women; Angmo prizes the few gonchas that her richer sister has given her over the years. Amchis’ services are likewise prohibitively expensive for treatment of all but a few maladies. Obviously, gonchas and amchis didn’t cost money before money existed in Ladakh, but that means little to a Ladakhi trying to clothe their family and keep healthy today. Watching the Sutu family, one thing seems certain; these people will never give up their electricity, their public education (shoddy though it might be), their cell phone, or their kerosene stove.

Yet it seems equally unlikely that they will give up the laughter, the creativity, the deep interpersonal familiarity that sustains them as much as dough and curd. Despite the 30 years since Ladakh’s passes were opened to the world, a great deal of Ladakhi culture has been retained. More and more Ladakhis are deciding that the flashy trappings of Western culture are not all so attractive as they seem, and are attempting to revive the traditions that have nearly fallen out of practice. Ringzen Lamo reports that more young people are studying to become amchis these days; Angmo’s younger brother, at school in Jammu, is one of them.

When I recall the jokes at which Dolma and Angmo fall over laughing, Tsering and Stanzin’s finger-games, grueling work in the hot sun, Abi-chomo’s prayer wheels made out of jam jars, pounding apricot pits to extract the sweet kernels inside, singing along to the radio, gossip, and fresh biscuits in milluk-tea—in short, the fabric of modern life in the Sutu family—I cannot help but believe the Ladakhis will win this latest struggle for survival. It will take a much better education system, and it will require their characteristic ingenuity. As with their physical environment, it cannot be a battle, but a game of negotiation: a shrewd and communal yanspa played with the conditions that threaten to overwhelm them.

Julia Harte is a student at the University of Pennsylvania. She spent the summer of 2007 in Ladakh through a program run by the International Society of Ecology and Culture.