Chenae Bullock. Photo by RaQuita Weathers, Beller Rouge Photography, LLC.

Chenae Bullock’s given name is Sagkompanau Mishoon Netooeusqua (“I lead Canoe I am butterfly woman.”) She is an enrolled member of the Shinnecock Nation in Southampton, Long Island, and also descends from the Montauk community in Long Island, New York. She is an entrepreneur who is deeply passionate about her Indigenous heritage. Cultural Survival recently spoke with Bullock.

Cultural Survival: Tell us about your recent business endeavors.

Chenae Bullock: I was selected to be the managing director of Little Beach Harvest, which is a Tribal business entity of the Shinnecock Indian Nation. It is the Shinnecock Nation’s cannabis business. We are working diligently despite the pandemic to get our medical dispensary up and running. In 2019 I launched my consulting firm, Moskehtu Consulting. People like to use Native-inspired things and ideas, whether for architectural design, clothing, curricula, exhibit curation in museums or art galleries, or business where you’re dealing with diversity and inclusion. What I’ve found over the last 15 years, being a Native and working in public and private sectors as well as nonprofit organizations, is that a lot of these organizations are unaware of how to approach Tribes due to a lack of cultural competency. They’re still thinking that we no longer exist. The whole purpose of Moskehtu Consulting is to bridge that gap, to become a liaison between the Tribal community and these businesses and organizations.

CS: Why did you pursue a business in the cannabis industry?

CB: The word Moskehtu means medicine in our language. Right now, we are in a time of healing in so many different ways, and that’s intergenerational. I think cannabis is probably the number one product out there right now that is able to help heal intergenerationally in communities. As a Tribe, and as Indigenous Peoples, cannabis and hemp have been used for thousands of years in many ways of our medicine and cultural practices. It’s not something new to us as Indigenous Peoples; it’s new for governments to actually begin to look at us as leaders in such an industry. Rather than focus too much on the cannabis industry, we should be highlighting the fact that there are young enterprising, entrepreneurial, culturally and traditionally taught and raised Natives out there who are rising up; whether they are in Tribal leadership or working in corporate America, whether they are sitting on a board for different organizations that may not even deal with Native people, they represent who we are. It needs to be echoed throughout the world that we no longer live in our wetus, teepees, or longhouses. We are not novelties. We have become unfortunately assimilated. My great cousin, Wayne “Red Dawn” Crippen who was one of the iron workers for many of the big cities throughout the country, said, “I decided to take those union jobs so I could learn how to use their tools.” And that’s why I’ve been encouraged by many of my elders to get out, to leave the reservation, to leave home, and to get the tools that are needed to come back and rebuild our nations. With my background and expertise, it’s time for me to move into this business as a leader in it, for the Shinneock Indian Nation.

CS: What barriers do you foresee, entering into this business as an Indigenous woman?

CB: There are always barriers; no matter what any community of color tries to do to raise themselves out of oppression, it’s going to be a challenge. Our Tribal leaders and community members have done everything in their power to meet with and do business with surrounding governments. We are either ignored or challenged and even sometimes taken to court. That being said, we’ve endured many challenges. We’ve endured many laws against our way of living, and we have all the tools that we need to bring ourselves out of economic despair.

CS: What does it mean to you to run a business as someone who is not only a woman, but also Indigenous?

CB: I am a Native American enrolled in a federally recognized Tribe. I also represent state recognized and underrecognized Tribes. But I’m also African-American. These are three different challenges that I have faced from the day I was born. Statistically, people like myself are classified as socially disadvantaged because we experience bias of a chronic and substantial nature. People like myself have very few intermediaries to succeed in a society that is replete of institutional voids. Prior to European settlement, Indigenous communities had a long history of dynamic economies and governance structures that we recognize today as the necessary ingredients for prosperity. Knowing that there are other people behind me with the same type of challenges, I have no choice—I’m left with no choice but to succeed by any means possible. It is my inherent obligation. So a business of this magnitude and with this amount of spotlight right now is a great opportunity not only for me, as a young woman, Native, African-American, for anybody that is looking to me as a role model. In my community we’ve been fighting for the last 400-500 years to raise ourselves out of this oppression. So any way that I can bring this business right side up, and build it from the ground up, it just speaks of evolution.

CS: What are the differences between businesses managed by Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people?

CB: Right now, our generation has been doing everything in our power to become conscientious of how we are being colonized and to break away from that and move back to our traditional structures. This provides an opportunity for us to incorporate that same type of traditional cultural structure into our businesses; in other words, how we communicate with one another. Instead of having a Robert’s Rules of Order when you come to a meeting, maybe you have it in a way of everyone knowing they are just as equal as the other person sitting across from them. In the dispensary business, we have many different non-Native partners and non-Native allies. We’re working to construct a dispensary and wellness center from ground up. You have Tribal representation from individually owned businesses like interior designers and architects, and then you also have non-Tribal partners as well, from project managers to environmentalists. Everybody’s coming together in this local area in which we’ve always lived as Indigenous people to do this project. I see it as a great example to the rest of the world how all people can come together and establish a successful business.

Little Beach Harvest is the Shinnecock Nation’s cannabis business. Photo by Don Goofy.

CS: How are Indigenous values reflected in Little Beach Harvest?

CB: As you look at history, and within our Shinnecock community, we’ve always been entrepreneurs. I come from a long line of whalers. Shinnecock people were also beaver fur traders and later went into tobacco. At one point in time, our communities were becoming wealthy due to our advantage in the whaling industry because of ancient whaling practices passed down from generation to generation. The crossover into oppression began when we couldn’t afford ships because money was being funneled internationally to certain families here in the Americas, particularly in the Hamptons. My ancestors were actually able to earn the money to own the whaling ships. But as the whaling industry began to decline internationally, that left our families in economic despair and we had to move into other creative ways of enterprising. Shinnecock has been known to lease different lands so that way we could make money for our community. I’ve heard the elders talk about the fields being potato fields and airports. From the very first time that the settlers came to Long Island, there were laws made against our way of living. There were certain areas in which we were not welcomed; there were certain things that happened that caused us to be murdered, or killed, or kidnapped.

Over the last 20 years, our community has been putting their lives on the line to protect our sacred burial sites. Over time, more and more million dollar mansions have been built on top of our ancestors’ bones. Our Tribal community leaders and sister Tribes have faced police brutality and threats for standing out there to protect our sacred burial grounds. Today, we move into different businesses, the cannabis industry. Again, here you have ancient teachings of medicinal uses for cannabis; we’re not new to this. Just like my ancestors, today we have aspirations to be able to own our own. First and foremost, Little Beach Harvest is the first Shinnecock Tribally owned and operated business for our Nation. Since time immemorial, we have been gifted by the Creator with specific values and responsibilities as Shinnecock people. The very foundation of Little Beach Harvest is the core values of the Shinnecock Nation. They include teaching and promoting spirituality, respect, responsibility, integrity, and unity in order to promote and ensure the health, well being, and safety of individuals, community, and the Nation. Keeping with these values for our Nation, Little Beach Harvest is a pillar for the ongoing development of the Shinnecock Nation’s economic renaissance.

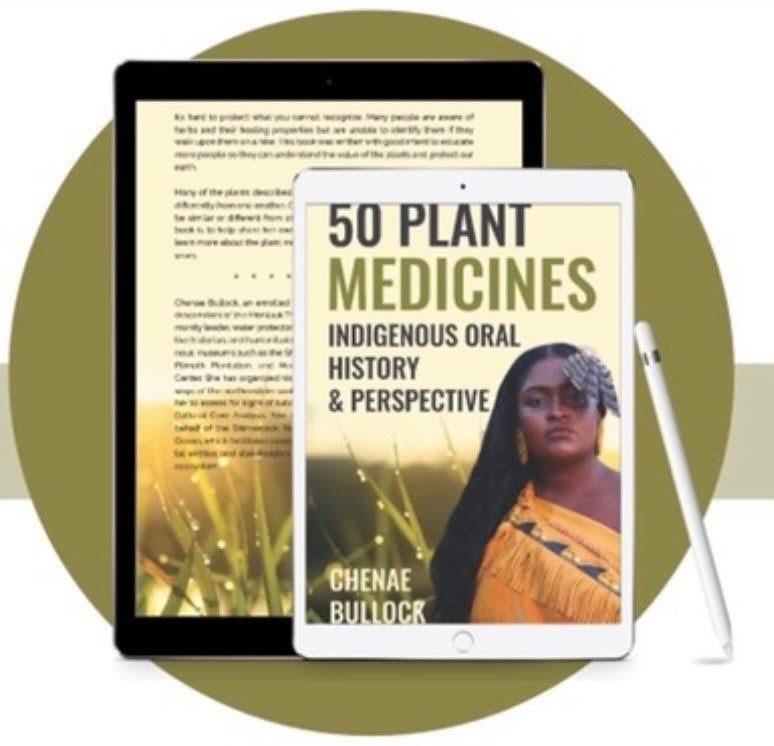

Check out Chenae Bullock's enew book, 50 Plant Medicines Indigenous Oral History & Perspective.