I vividly remember 13-year-old me, a tiny, effeminate, bespectacled young individual born and raised in a poor community that I now call a refugee camp, a place called Lavender Hill, hidden behind Huri ǂOaxa or Table Mountain, a place where no one was supposed to live. Our ancestors didn’t live on these dry sand lands.

We, who believed that post-apartheid 1994 South Africa would be the dawn of our !norasib, our freedom. Our Khoi people who were the first to !kham, or fight colonizers, who were the first to lose our wealth and our freedom, and here we were, erased again, stuck in the language of our Dutch enslavers, in a community like so many Indigenous communities in the Americas, filled with non-stop gang unrest and a people erased from sight, buried alive.

I am a person formed in the womb of a Khoi taras, she who carries the world’s most ancient DNA; she herself a victim of human trafficking, who at the age of 16 was sent away to be a slave in the households of colonizers like the many Khoi women before her, finding herself in //Hui!Gaes, or what colonizers would later call Cape Town. Cape Town, which they turned into Cape of Torments, would also be known as the “Tavern of the Seas,” our one-time paradise corrupted and destroyed by colonizers.

I struggled to navigate a world that made me feel so unworthy, where my attraction to another human being was unnatural and immoral in the eyes of a white Jesus and his mother. I struggled to find my way amongst a people in a book who didn’t resemble either my family or community, in a home where the Bible filled this very prominent place; this book with all these verses of Sodom and Gomorrah, condemning people like me as “sinners and sodomites,” words and identities my aboxan, or ancestors, never heard of before the arrival of these invaders from Europe, to burn in the pits of a colonial imaginary hell.

We would never burn another human being. We were too much of a Khoikhoi, people of people guided by the belief that you are a person, that your humanity matters more, and that you are worthy of !goasib, or respect. Depression, isolation, and self-hate are what I would know from a very young age. Whilst my peers would be playing games or just enjoying what appeared to be their carefree existence, I struggled with self-acceptance, fighting what I considered to be immoral and punishable thoughts in silence. I think the silence was probably the hardest part. It was also a time of intense bullying. I still look back at my years of school, mostly remembering the beatings, the scars, and the name calling that never ended, the fear of using the bathroom, the isolation, as if I was somehow a diseased person; Christian, homophobic teachers, many of whom said nothing, in spite of witnessing the terror on my body and mind. Why would they have said anything when their Bible justified my oppression? I prayed to white Jesus, asking him to !nora, or free me from these “dirty” thoughts, and yet they never left me.

Some of my earliest memories are of walking with a friend, a Khoi and Queer person, who was stoned by a group of young men. Another memory that still haunts me is seeing this young man, his eyes filled with so much anger and hatred toward me, looking at me whilst kicking his soccer ball with all his strength into my face. My nose bleeding, my spectacles shattered, only to be told by my teacher that I was to blame, and not once given the opportunity to explain my side of the story.

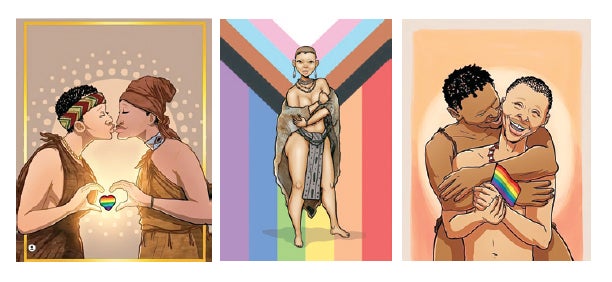

Art by Dav Andrew (@dav.andrew1).

School left me traumatized, tormented, suicidal, and depressed. I was lucky enough to be in a space after school where I could start my healing journey. Many psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, self-help courses, and two years of antidepressants saved me from suicide. But it really was re-connecting to my Khoi identity, reconnecting to my African identity, learning the gowas, or languages, of my ancestors, hearing the stories of my aboxan, hearing that words in our language speak to the existence of /Gui/nam, or same-sex love.

It allowed me to return to a time before the arrival of these pirates from the Netherlands who disrupted our lives, forcing us to know only their words, corrupting our belief systems and internalizing their many toxic ideas, especially those of transphobia, homophobia, and the fear of our Two-Spirit individuals. It’s interesting how we as Khoi people are the most erased, and yet we are always the ones quoted in conversations about homophobia being un-African. It was documented that our Khoikhoi people had words like koetsire, describing men seen as sexually open to other men, and soregus, which describes a friendship that entailed same-sex lovemaking.

One of the first documented same-sex relationships in South Africa was that between a Khoi man, Klaas Blank, and Rijkhaart Jacobsz, a Dutch man, on Robben Island between 1718 and 1735. The two men were in prison on Robben Island and were in a relationship for more than a decade before they were drowned for committing what the colonizers regarded as unnatural acts. I always see their story not just as a Khoi people, who provided both food and comfort to colonizers and enslaved people on this land, but that our love transcended the beliefs of the church, which continues in many instances to shame same-sex love.

What was also very interesting was discovering that Khoikhoi as a language is rooted in taras, or women. This is no surprise considering that Khoi societies were matrilineal societies. It was our women who tani, or carried the most influence in our societies, and even today very little has changed. You can go to any Khoi community, and despite this “coloured” identity forced upon us, we still see how our women are leading in church, in schools, in our homes. She makes the majority of the decisions. Taras means women, but also supreme leader.

Khoikhoi as a gowas, or language, also has what is called a communal gender that allows you to add the letter ‘i.’ So if you are unsure of the gender of a person, adding the ‘i’ becomes the equivalent of the ‘they’ we know today. I love this because it really goes back to the name we had for ourselves: Khoikhoi translates into people of people, a reminder of your intrinsic value as a person, anu, or worthy of love and respect, in contrast to colonizer societies that value you only in terms of colonial worth.

Sadly, we have also been witness to the most brutal forms of violence to our Khoi 2SLGBTQ+ communities. Again, it speaks to how the words on a people’s tongues corrupts the beliefs and thoughts of a people. And when our thoughts are corrupted, we are corrupted.

I think of David Olyn, who was murdered by and set alight by our own Khoi people. They spoke about killing a “moffie,” and because the historical violence of our ancestors is hidden from us, they didn’t know that hundreds of years ago we were savagely burnt alive by these Dutch colonizers, burnt for our land and our cattle and to destroy our communities.

I also remember Kirvan Fortuin, this most talented Khoi dancer from Macassar in the Western Cape, who was stabbed to death by another young Khoi person. She told everyone about a moffie that she was going to hurt. How did we go from this place where we celebrated our taras and all that was from her womb to hating ourselves and her?

I wished I had this information when I was younger. It would have saved me from much hurt. But we will share and remind the next generation that many of our phobias that we tani, or carry, today, are but a product of others.

— Toroga Denver Breda (Khoihoi) is a Hui!Gaeb/Cape Town-based Khoikhoi First Nations gowab ╪Khaikhai-ao-I (language revitalizer), karetsanas-ao-i (poet), and kuwiri(disruptor). Through his kurus (art), he challenges the kakapusa (erasure) of South Africa’s Native languages and the stories of his abogan (ancestors).

Top photo: Definition of /Gui/nam, or same sex love. Photo by Toroga Denver Breda.