Elsebet Henningson was born in Jutland, Denmark on June 1, 1926, but from birth she was called Pia, Danish for “girl,” because she was the only daughter in a family with three sons. She grew up in Denmark and earned a degree in nutrition before her parents sent her to England at age 21, where she spent her first years working for the woman who had been Winston Churchill’s secretary during World War II. “My English was incredibly faulty,” Pia recollected in a 2005 interview. “And later in life I was so upset that I never really was able to talk to her properly. If I had spoken the language I would have had fantastic conversations.”

Pia went on to live in the home of psychiatrist Alice Roughton, a place that was known as a crossroads for future leaders in world politics and medicine, and later took literature courses at Oxford. But it was at a party back at the Roughton home where she met David Maybury-Lewis. During their courtship, Pia continued to learn English and David studied modern languages at Cambridge University. The two were married in 1953 and lived in England while David continued in school. Interested in anthropology and wanting to travel, he was encouraged by a Cambridge professor to pursue fieldwork among the Indigenous tribes in Brazil—relatively unexplored territory for anthropologists at the time. David left for Brazil in 1953, and Pia followed several months later via a 24-day trip on a freight ship from Norway.

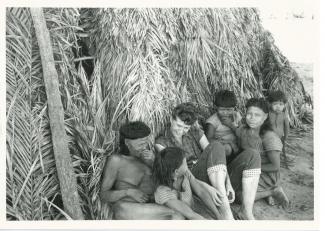

In São Paolo, the couple studied anthropology and planned their fieldwork among the Xavante, a tribe living remotely in the savannah of Mato Grosso. The stories of the devastating impacts of development on Indigenous populations that the Maybury-Lewises first witnessed in Brazil’s interior are well known among Cultural Survival supporters and have been retold several times by David in his own writing and in the well-received Millennium film series. Before living with the Xavante, they lived with the Xerente, a neighboring tribe who spoke a language close to Xavante.

On their first visit to the Xerente, Pia noticed the deplorable racist attitudes Brazilians held towards the country’s Indigenous Peoples. David took a turbo-prop plane and Pia, due to lack of space on the flight, again followed, in a boat. “The [riverboat] captain heard that we were going to see the Xerente. He said at night he just stops in the middle of the river because they eat you. There wasn’t a horrible thing they didn’t say about the Indians,” she recalled. After living with the Xerente for 18 months, the MayburyLewises returned to England and Pia gave birth to their first son, Biorn. When it was time for David to return to Brazil to begin his fieldwork with the Xavante, Pia’s family encouraged her to stay behind and take care of the baby, but Pia insisted on following her husband and bringing her child with her. David, Pia, and Biorn spent several months with the Xavante over the next year. Pia worked in the fields with the other women, carrying Biorn on her back in a sling wherever she went. “He was a toddler. A little baby would have been easier,” she quipped.

The Maybury-Lewises spent nearly a year with the Xavante during their first trip and then returned to Oxford where David finished his dissertation. They moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the early 1960s, when David got a job in the anthropology department at Harvard University. Their second son, Anthony, was born in Massachusetts a few years later. They intended to be there only for six months, but remained for over 50 years.

Even after Pia and David settled in Cambridge, their experiences among the Xavante stayed on their minds and they felt a growing urgency to do more than “study” Indigenous Peoples. The tribe faced increasing encroachment from settlers and suffered because they lacked educational and health services. “In those days [the Brazilian federal Indian agency, called FUNAI] was really sitting on a pile of money. And we were wondering what could be done with that money if the Indians got it themselves. Education would help them to figure out what could be done. We heard other people say, ‘well, we should do something for the people who we studied.’ It was talk, but no doing.”

In 1972, David and Pia decided to do. Along with Harvard colleagues Evon Vogt, Jr., and Orlando Patterson, the couple registered Cultural Survival as a nonprofit and started raising money for projects to aid the Xavante. “Our goal was to make life easier for Indigenous people, and to inform other people about Indigenous Peoples’ ways,” Pia said. “I wanted people to really understand Indigenous people. The great majority of peoples don’t understand each other.” Cultural understanding, Pia believed, can go a long way toward ending violence against the world’s poorest and most marginalized peoples.

Cultural Survival’s first home was the fifth floor of Harvard’s Peabody Museum, where Pia handled the logistics and fundraising to get the organization off the ground. “We weren’t really absolutely sure what we were doing in the beginning,” Pia said, but before long Cultural Survival started receiving appeals for aid from Indigenous Peoples and their advocates. Its first campaign helped pay for a Xavante man to go to school to become a nurse, with the intention that he would bring his skills back to his community. When a London-based organization called to say that malaria had broken out in Yanomami territory in Brazil, Cultural Survival raised $3,000 to send medicine. Another group needed boats to allow them to collect nuts, so Cultural Survival raised the money to purchase those.

Pia first brought interns into the office in these early days to help write fundraising appeals for the $500 and $1,000 that were needed for these small projects. Internships were not yet a routine part of the college experience, but young people were willing to work for free for an up close education about Indigenous rights and nonprofits. More than 1,600 college and graduate students, as well as a few high school students and some mid-career professionals looking for new life directions, have passed through Cultural Survival’s offices; Pia often referred to interns as the “lifeblood of Cultural Survival.”

Pia was also renowned as a party planner and hostess, a reputation she first earned from the balls she organized in Cambridge in the 1970s to raise money for Cultural Survival projects. Although she admitted that the financial success of these parties was questionable, they attracted the Harvard social circles that became some of Cultural Survival’s greatest donors and attracted attention for the festive Cultural Survival Bazaars, the organization’s most successful fundraisers.

Cultural Survival supported and helped spread the word about the Indigenous rights movement since its inception, and many of the organization's programs started with Pia. She also started the Cultural Survival Quarterly, which began as a newsletter. David, an anthropologist whose combined academic training, deep compassion, and scholarly ambition were the seeds of Cultural Survival’s mission, was the organization’s figurehead and lent it credibility. But he always credited a great deal of its success thanks to Pia’s work and innovation. “Pia was the person who had an endless stream of ideas,” he said in 2006. Still, Pia often brushed off introductions that labeled her the “co-founder” of Cultural Survival and gave full credit to her husband.

Together with rug seller Chris Walter, Pia planned the first Cultural Survival Bazaar in 1975. Walter was the only vendor and spread out his rugs and kilims on the top floor of a house near the Harvard campus. The Bazaars moved to bigger venues over the years as their reputation drew more vendors; the annual December Bazaar at Harvard Law School’s Pound Hall has become a traditional part of many Cantabrigians’ holiday shopping season. Culture may be a commodity in today’s market, but Pia’s original mission to promote cultural appreciation by showcasing Indigenous crafts endures, at the very least, to provide context for the latest trends.

Many will remember the Maybury-Lewis’ Cambridge home as a refuge and crossroads for family, friends, and the occasional Cultural Survival intern. Over the years it welcomed well known thinkers and influential human rights activists. Pia once said that the ideas and initial plans for Doctors Without Borders originated from a conversation that took place among guests in the Maybury-Lewis home.

Pia befriended the other faculty families in her neighborhood, though she never fully adopted the traditional role of a Harvard faculty wife. Cynthia Sunderland, a long time close friend and neighbor, recalled that Pia primarily spent her days at Cultural Survival and socialized with other Danish immigrants—a group that came to be nicknamed the “Danish Mafia.” Rather than join the clubs reserved for the wives of faculty members, she was a founding member of a drinking club and a bridge club. “She [was] always interested in people and interested in the young. Which probably kept her young,” Sunderland said. “She [had] enormous generosity. Not only hospitality in the house, but sort of a generosity of the spirit toward people.”

At first meeting, Pia’s wit could be jarring, her questions pointed, and her conclusions outrageous. But her interest in other people’s stories was genuine, and she almost always won new acquaintances over long enough for them to realize that she was usually right. It is this trait that allowed her to get away with saying and doing things that most other people only think. David, who died in 2007, once said of his wife, “Pia is outrageous. She says outrageous things. And [when] I think I just can’t take it anymore . . . then she makes me laugh. I think that is the great gift.”

Cultural Survival deeply mourns the loss of our beloved Pia, who passed away on August 4, 2015 at age 89 after a long battle with lung cancer. She was surrounded by her loving family and friends at her home in Cambridge, MA. She was one in a million.

Photo: Cultural Survival co-founder, Pia Maybury-Lewis, with Xavante families during her first visit to the region of Mato Grosso, Brazil in 1958. Photo courtesy of Pia Maybury-Lewis.