Clothes have the power to reflect, and at times, alter, the socio-political climate: “You can even see the approaching of a revolution in clothes,” Diana Vreeland, former editor-in-chief of Vogue, once said. Apparel also acts as a visual framing for activists, as their personal presentation also presents their cause. Women of the civil rights movement, for example, emphasized Sunday best complete with dresses, hats, and gloves, which highlighted their non-violent activism and echoed their political grace. More recently, the #TimesUp movement used fashion to great effect at the 2018 Golden Globes awards ceremony, where the coordinated black evening gowns gave a funerary edge

to the usual glitz.

Fashion, whether engaged actively or passively, is a codification of our beliefs about ourselves and the world in which we live. Most importantly, this codification is self-realized: we are both canvas and artist. Denim jeans, for example, are the result of decades of hard-won feminist victories; they narrate women’s liberation, the fight for equal pay, and the escape from the corset. Every time women put them on, they engage with this narrative. Clothing can be dissent, and accessories, advocacy.

Around the world, Indigenous designers are leading artistic revolutions. In Ecuador, there has been a revitalization of traditional clothing by younger, modern fashionistas, and with them, modelling agencies celebrating Indigenous beauty and renewed pride in Quechua artistic heritage. Such has been the wave of Indigenous fashion that in 2017 the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian staged "Native Fashion Now,” an exhibit celebrating the work of over 70 Indigenous designers over the last 5 decades. First Nations designers in Canada have likewise been at the forefront of creating modern, Indigenous-inspired fashion with mass market appeal. Last November saw the second annual Otahpiaaki Fashion Week held in Calgary. Fittingly, the theme was “Pride and Protest,” and showcased over 50 designers from 18 Tribal Nations celebrating their communities’ artistic legacies.

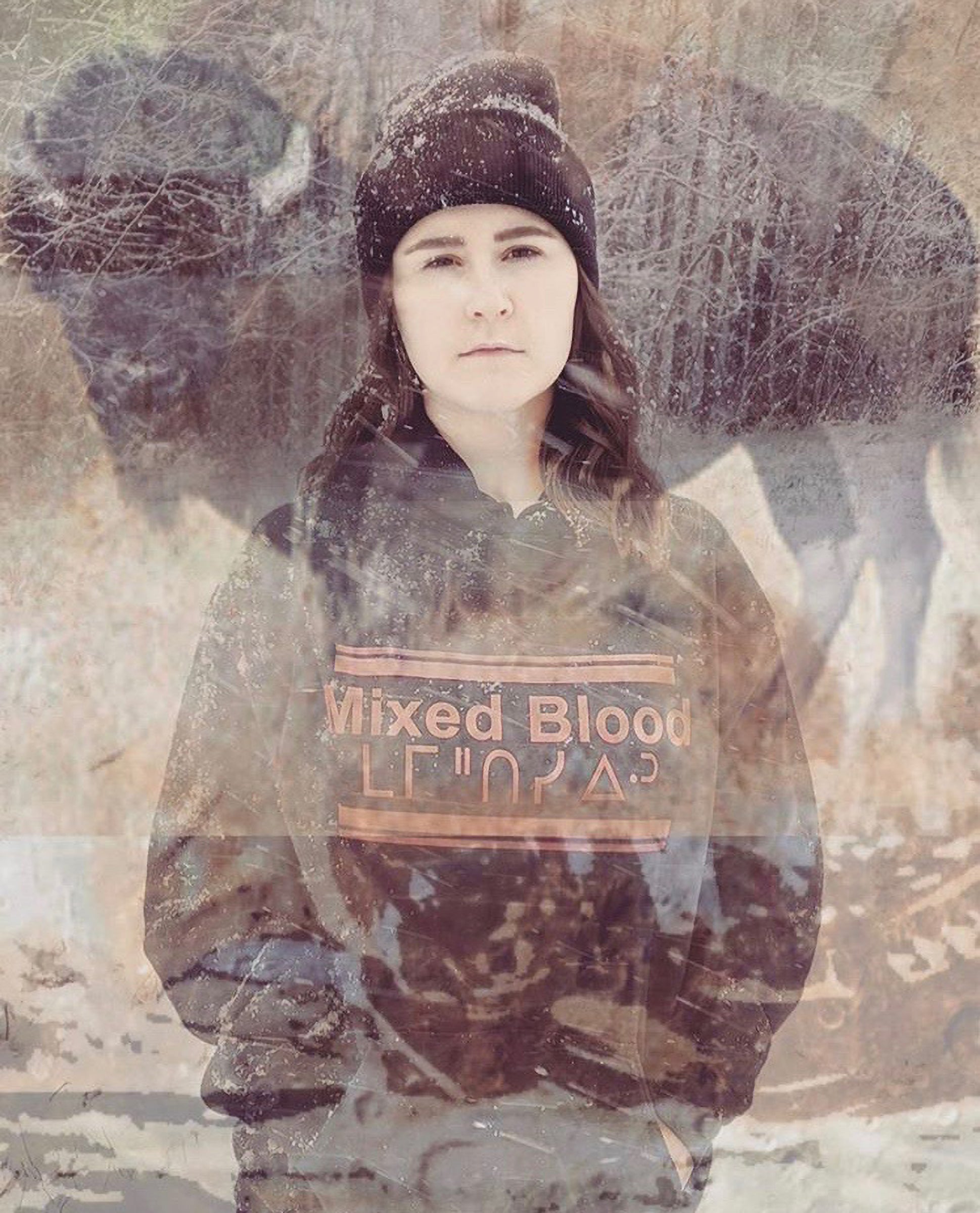

But the revolution we see approaching in these lines is not purely aesthetic. In Canada, fashion seems to be the barometer for something much bigger, articulated by artisans. “I saw fashion as a way to engage with younger generations,” says Brandi Morin (Cree, Mohawk, and French), who started her own clothing line, Mixed Blood Apparel. When her designs were showcased in a standing exhibition at the Otahpiaaki Fashion Week, Morin had only been running her business for two weeks. “I was on maternity leave from my job as a journalist and had been looking to engage and inspire a new generation. I was frustrated by the adversity faced by Indigenous communities and reading pages of negative statistics. I saw a natural link between language and clothing, with both being means by which we express ourselves. I wanted people to rediscover and be empowered by their heritage. This led me to become a designer and an entrepreneur,” she says.

Mixed Blood Apparel began with a pair of leggings and Morin’s goal to empower, celebrate, and revitalize Indigenous languages and cultures. “One of my first designs was the Maskawisiw legging. In Cree, maskawisiw means ‘he/she moves in a powerful way.’ The idea was to remind the wearer of their own power,” she explains. Another pair of leggings drapes the wearer in the hand-written stories of Morin’s grandmother. From Indigenous history to Indigenous present and future, Morin’s UNDRIP collection—a reference to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples—is perhaps her most explicitly political collection to date. The UNDRIP leggings have the Cree syllabics for “he/she stands with it.” In Canada, the Declaration has been officially endorsed but remains largely unimplemented.

The power of language is emblazoned across the entire line. Morin herself articulates this: “Language is at the very core of who we are. It is more than communicating. It’s how we remember our history and declare our future. Our ancestors passed on traditions and knowledge through language that have been alive for millennia. Language is used to preserve our cultures, cultivate our worldviews [and] self-determination, and express our human rights.” Through bold lettering, she chooses to scream these once-silenced alphabets, so that wearers are empowered while also continuing the revitalization process. “I want these pieces to spark conversations, for the words to be explained and taught. Visually the words are art, adorning the clothes, but they are never purely, passively aesthetic. I encourage you to learn and speak your language in whatever form that takes; whether you learn from your Kohkums and Mushums, your aunties, uncles, or other relatives...if you have no one that knows your other language, then seek it out.”

Morin says she has received several emails asking if non-Indigenous people could wear pieces from the line. There is a danger of the “Urban Outfitters effect,” the trickle-down of

Indigenous ontologies until they lose their significance and power, becoming a mere adornment to make the wearer look more cultured. But Morin is undeterred: “My line is for everyone, to empower everyone through their culture.” The spirit of the brand is best encapsulated in a shirt with reads “tawâw,” with Cree syllabics above. Translated, the word means “Come in, welcome, there is room.” Morin has received some negative feedback from those who see the shirt as making a contemporary political statement about immigration. But, she maintains her message is about “how we, as Indigenous Peoples, will welcome in everyone—even if that welcome wasn’t shown to us.”

At its heart, “there is room,” is very much what Mixed Blood Apparel is about—creating a space for diversity. “Each piece is an opportunity for teaching, sharing. I imagine people

asking about what the words mean on someone’s shirt and the wearer explaining the meaning. This is how these languages survive and grow. Now someone else knows a word in Cree or Mohawk,” she says. Even the brand name, Mixed Blood, looks to recognize the diversity of identities across First Nations citizens and beyond. “I see my brand as part of an Indigenous renaissance, one which will be cultural, artistic, political, economic, and spiritual, but ultimately led by artists. This fits into the prophecy given by Métis leader Louis Riel, who prophesied that our people would sleep for 100 years and that artists would reawaken them and return their spirits.”

Looking at the rise of Morin’s line and Indigenous fashion in general, it becomes evident that a revolution is growing: one that champions diversity and encourages Indigenous entrepreneurship, listening to the past but without ever losing sight of the future. “Indigenous Peoples are less likely to be self-employed than the rest of the population. In the next two decades the Indigenous population in Canada is likely to exceed 2.5 million. Can you imagine the incredible impact if more Indigenous Peoples became business owners?” Morin asks.

Morin, in the Mixed Blood Apparel website’s manifesto, describes the current moment as a renaissance. “I dreamt of the word ‘renaissance,’ and I believe a lot in dreams, so

when I woke up I looked up the word and it fit perfectly with what was happening, with what I was trying to do. This is an Indigenous renaissance.” The Renaissance period changed our concepts of art and beauty and left humanity permanently altered. It was a period of self-reflection, but perhaps most importantly, self-education. People began to be aware of the rich legacy of the past and used it to improve the future.

The Renaissance pushed us into new ways of thinking, acting, and being. “In the International Year of Indigenous Languages, nothing seems more appropriate than recognizing the value of Indigenous languages and cultures, with the charge led by the artists,” Morin adds. Morin’s new collection debuts in March, and her work will also be showcased at an Indigenous Fashion show coinciding with the Western Canada Fashion

Week. The revolution is coming, and not just in Canada. And this revolution has a dress code.

Check out Mixed Blood Apparel at mixedbloodapparel.ca

Photos: Sisters Josie and Brace model Mixed Blood Apparel gear.

Faith models Mixed Blood Proud hoodie featuring Cree syllabics.