By Nataly Kelly

Much has been written about the Shuar, an Indigenous group from the Ecuadorian Amazon; many words have been used to describe them. Warriors, head-shrinkers, and shamans are some of the most common associations. But one word that is not typically seen in reference to the Shuar? Poet. Until now, that is—especially if María Clara Sharupi Jua has anything to say about it.

As the Battlefield Changes, So Do the Battle Plans

The history of the Shuar has been told predominantly through the lens of their warrior culture. Known for their fierce independence, the Shuar are often viewed as one of the few “winners” in the continuous battle that Indigenous people must fight to maintain their cultures, languages, and traditions. Their success arguably can be attributed as much to their strategic thinking and adaptability as their superior fighting skill.

In 1599, the Shuar shocked the Spanish by successfully driving them out of their territory. They are the only Indigenous group ever to achieve such a victory over their would-be colonizers, and their exceptional skill in battle enabled them to retain their independence for centuries. But in the 1940s the Shuar found themselves facing a new kind of threat: oil. Once oil was discovered in the region, missionaries and other colonists soon followed. The Shuar recognized that a different kind of fight—a nonviolent, political one—would be needed to protect their culture. They responded by establishing the Federacíon Interprovincial de Centros Shuar-Achuar, a political alliance that has been working to represent and protect the Shuar people’s interests for almost a half century.

Today, as the forces of globalization expand and the world continues to become more interconnected, the Internet offers new possibilities for ethnic minority groups fighting for the survival of their cultures and the languages that hold their collective knowledge. For a language like Shuar, which is spoken by some 40,000 people, the Internet has become a vital platform for disseminating the community’s native language and the ideas uniquely expressed within it.

Words as the New Weapon

María Clara Sharupi Jua is harnessing the power of words to help carve out what she hopes will be a fuller appreciation of her culture. “The Shuar culture is highly publicized but little understood...Many people continue to think of us as savages,” she says.

Even within Ecuador, Indigenous groups often face stereotyping and discrimination. Sharupi was born in the Amazon rainforest and currently lives in the capital city of Quito, where she is pursuing a university degree while also working full time at a government office. She says that Ecuadorians often question her about why she is living in an urban environment instead of in the jungle. “The questions people ask me range from ignorant to downright rude,” she says. The thing that Sharupi finds most disrespectful is when people fail to address members of the Shuar community by their names, instead referring to them with generic titles such as “la María” or “doñita.” She explains, “I always tell them, ‘I have a name, so if you’re going to address me, you need to use it.’”

Sharupi feels that the Shuar are often looked down upon, as though people believe they are somehow lacking in knowledge or are incapable of accomplishing the same things as others. However, she notes that there have been positive changes recently, among youth and women in particular. She explains, “I think that President Correa has given us greater recognition, particularly by making sure the Constitution and all of the laws are available in our mother tongue, which shows respect for us as human beings.” Sharupi was part of a team of individuals who helped edit the translation of the constitution in Shuar.

According to Sharupi, foreigners are also guilty of disrespectful treatment toward the Shuar. “When foreigners visit our communities,” she says, “it’s as if they hope to see a culture of savages. They want to live among people who are irrational, walk around naked, and have nothing. They want to report only on what’s different – not on what we have in common. I often feel they look at us solely as the finishing touch that enables them to complete an anthropological study or a graduate thesis.”

Through her poetry, Sharupi hopes to reveal a more complete and nuanced picture of the Shuar people, using an authentic voice that comes directly from her community. “Poetry is important because it’s our way of life. Poetry is song, everyday life, ritual, and where the heart and soul of the world unite. It’s a form of paying tribute to what exists beyond just what we see. It is also important for keeping the memory of our ancestors alive for our children and their children.”

In Sharupi’s eyes, the Shuar language is full of beautiful concepts that reflect cultural values far beyond just the typically associated warrior attributes. Her favorite phrase is “enenteimjai chichasta,” which simply translated means, “speak from your heart.” But the phrase also implies the opening of one’s heart to another person, speaking to them sincerely and free of any filters. Another of Sharupi's favorites, “yuminsajme,” is a form of thanking someone but in a way that conveys a much deeper sense of gratitude, closer to “thank you from my very being.” Sharupi explains: “In this expression of thanks, the person gives all of their love to the other person, not as if that person is simply a person to whom love is directed, but as if that person is actually an extension of one’s self.”

Translation Is the Best Defense

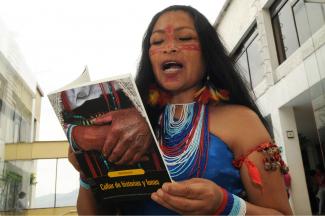

Sharupi and her poems are steadily gaining international acclaim. She has been published in numerous literary journals and anthologies, including Collar de historias y lunas, an anthology of Latin American female Indigenous poets, and Amanece en nuestras vidas, the first book of poetry from Ecuadorian Indigenous women writers. She has conducted poetry readings at universities and book fairs, and she was invited to participate in the 2012 International Poetry Festival in Medellín, Colombia. She is also a member of the World Poetry Movement, and recently participated in the first International Colloquium of Indigenous Women Writers. Sharupi is currently working on a trilingual collection in Shuar, Spanish, and English that will include poetry, stories, and songs in celebration of the wisdom embedded in her culture.

Translation can help a poet reach a wider audience, and Sharupi knows firsthand how powerful it can be. Three of her poems have been translated into English and published by the London-based Poetry Translation Centre. Making these poems available in English, and online, is an important milestone because her work is now accessible to a world of readers who would otherwise not be able to understand it. Through her poetry, Sharupi hopes to add a new chapter to the Shuar legacy; one that extends beyond the typical associations of their warrior heritage. If the pen truly is mightier than the sword, then perhaps translation can give even more power to the pen—and the people who hold it.

AYA ENENTEIJAI TAYI Másh inijiatar, éntsa michamchat nunkan imichna aintsank jíi kia takatsui ewejrum-sha atsawai ame áarma nuna mejentsat nakua wakeraj ame wakannish atsana nui yamai pujai, atakak pujatsji winia kanarmari, penkesh chicham-ka juratsme winia enenteir-yajá kampuntinnium enenteimiawai | PARADISE CAME Drenching myself, like cool rain on mother earth You have no eyes You have no hands I want to kiss your words

We don’t know if you’re here or not You don’t threaten my childhood dreams I think of my beloved jungle |

By María Clara Sharupi Jua

(English translation by Nataly Kelly)

--Nataly Kelly is the translator of María Clara Sharupi Jua’s works in English and a former Fulbright scholar in Ecuador. She is the co-author of the newly released book, Found in Translation: How Language Shapes Our Lives and Transforms the World.

Bringing Shuar Poetry to the World through Digital Multimedia

- Read María Clara’s poems in English as translated by the Poetry Translation Centre

- Listen to María Clara reading her poems in Shuar and Spanish

- Hear María Clara on Ecuadorian radio station Radio Visión FM

- Explore additional press coverage and updates in English