La Semana de la Moda de Nueva York, que se celebra dos veces al año, es el momento en que tanto las grandes casas consolidadas como las y los diseñadores emergentes más destacados presentan sus nuevas colecciones ante un público exclusivo de medios, compradores y celebridades, marcando las tendencias globales de la temporada. Aunque en ocasiones se ha destacado a diseñadoras y diseñadores Indígenas, su trabajo ha permanecido en gran medida en los márgenes.

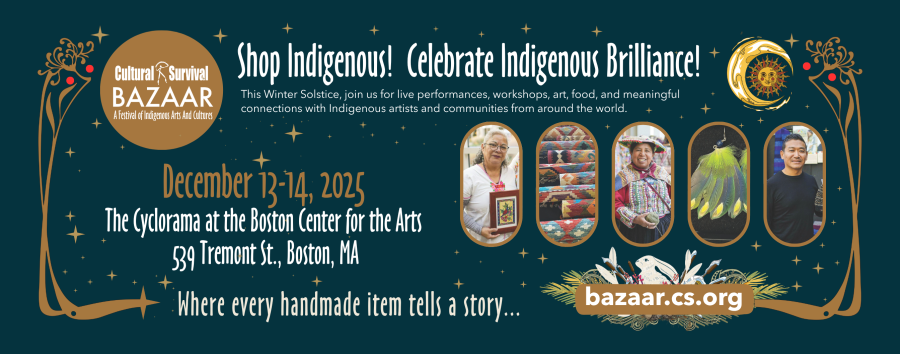

Ahí entra en escena Relative Arts en Nueva York. Este dúo dinámico de fashionistas Indígenas, empeñadas en cambiar el statu quo, ha creado la primera boutique de moda de la ciudad dedicada exclusivamente a exhibir moda Indígena contemporánea y ahora está inaugurando la primera Semana de la Moda Indígena de Nueva York. Korina Emmerich (Puyallup) y Liana Shewey (Mvskoke Creek) han hecho realidad un sueño colectivo: llevar el estilo Indígena contemporáneo al centro del escenario. Cristina Verán conversó con ellas sobre los caminos que las llevaron hasta aquí.

Cristina Verán: Como muchas personas creativas, ambas llegaron a Nueva York para construir una vida creativa. ¿Cómo se conocieron y conectaron sus pasiones?

Korina Emmerich: Soy diseñadora de moda y artista y cuando estaba creciendo no había una verdadera visibilidad para las y los diseñadores Indígenas. Era como si ni siquiera existieran; se sentía muy solitario. Así que me mudé aquí para seguir una carrera. Liana y yo nos conocimos en la American Indian Community House en 2018. Nos dimos cuenta de lo parecidas que eran nuestras misiones y empezamos un colectivo activista. Somos personas creativas y también fans de la moda, y para nosotras, estas cosas van de la mano.

Liana Shewey: Mi experiencia profesional se centra en la producción de eventos para salas de conciertos, además de ser organizadora comunitaria. Nos unimos como creadores, artistas, narradores —radicales Indígenas de Lenapehoking— para organizar movimientos de base y celebrar nuestra comunidad en este proceso de revitalización y renacimiento de nuestras culturas.

[*Lenapehoking comprende el territorio no cedido del pueblo lenape, sobre el cual se construyó la ciudad de Nueva York.]

CV: Como diseñadora, Korina, has tenido una trayectoria personal dentro de la industria de la moda. ¿Qué experiencias han dado forma a tu visión y a esta misión?

KE: He presentado mi propio trabajo en la Semana de la Moda de Nueva York antes. También he participado en el Indian Market de Santa Fe, en la Semana de la Moda Indígena de Vancouver y en Fashion Arts Toronto, entre otros, trabajando con, y encontrando inspiración en, personas como Amber Dawn Bearrobe, Sage Paul y Joleen Mitton.

LS: Yo había estado apoyando a Korina durante algunos de esos desfiles y me di cuenta de que estos eventos tradicionales de la industria de la moda simplemente no están diseñados para nosotros, ni para los diseñadores Indígenas, ni siquiera para los modelos que desfilan por las pasarelas. Los maquilladores no sabían elegir los tonos adecuados para su piel, ni sabían peinar bien el cabello de nuestra gente, no lo respetaban. Sin embargo, en lugar de exigir que sus desfiles se adaptaran a nosotros, nos dimos cuenta de que teníamos que crear nuestro propio espacio.

CV: Eso nos lleva a Relative Arts, la primera boutique dedicada a mostrar moda Indígena contemporánea en Nueva York. Es más que una tienda: es un punto de referencia. ¿Cómo se fue concretando todo y qué consideran que ofrece este espacio?

LS: Korina entendía el mundo de la moda y tenía muchos contactos en él. Además, las dos conocíamos a muchos pensadores y activistas Indígenas radicales. Aunque puede que sea secundario con respecto a lo que hacemos, el impulso inicial fue crear una especie de espacio seguro que fuera realmente nuestro.

KE: Queríamos reunir a increíbles creadoras y creadores Indígenas que usan prácticas tradicionales de manera contemporánea y, además, de forma sostenible. Hay muchísima innovación ocurriendo en los territorios Indígenas, y sin embargo, la mayoría de las veces se nos sigue presentando en lugares como las tiendas de museos, sin reconocernos como parte del universo más amplio de la moda.

CV: Cuéntenos cómo lograron representar las visiones de las y los diseñadores Indígenas y, al mismo tiempo, asegurarse de que maquillistas, estilistas y modelos también reflejaran toda la diversidad de lo Indígena.

KE: Tuvimos nuestra propia directora de casting de modelos, Nishina Shapwaykeesic-Loft (Kanien’kehá:ka) y así nos aseguramos de presentar modelos que representaran la diversidad dentro de nuestra comunidad Indígena. Imagina: antes y después de cada uno de nuestros desfiles, ¡todo el East Village estaba lleno de estas bellezas nativas caminando por ahí! Merecemos ese momento de street style, que todo el mundo repare en sus atuendos.

LS: Los estilistas y maquilladores fueron convocados por Deyah Cassadore (White Mountain/San Carlos Apache) y Amy Farid (Osage), y con el equipo de producción, las personas voluntarias, el personal de sala y demás, se convirtió en una pequeña economía local para profesionales creativos y artistas Indígenas en Nueva York. Había al menos 100 personas en el equipo trabajando, ampliando sus redes y fortaleciendo sus habilidades.

Photos by Cristina Verán.

CV: ¿Cómo lograron afrontar los costos que, de otro modo, serían prohibitivos para hacer todo esto en una ciudad tan cara como Nueva York?

KE: Bueno, al final este año no conseguimos realmente financiamiento externo, así que salió de nuestros propios bolsillos —todavía lo estamos pagando— y gracias a la colaboración de nuestra comunidad.

LS: Para nosotras, era fundamental mantener la Semana de la Moda Indígena de Nueva York accesible para todos los niveles. Los grandes desfiles no Indígenas de la Fashion Week pueden costar entre 500 y 2 000 dólares por entrada, pero nosotras pusimos un tope de 45 dólares al precio de los boletos.

CV: ¿Cómo abordan las preocupaciones sobre qué es apropiado que lleve quién, entre las personas fans de la moda Indígena?

KE: Hay prendas como moda y prendas como regalia (vestimentas ceremoniales); por ejemplo, una manta decorativa frente a una manta utilizada en ceremonia. En el caso de las ribbon skirts (faldas con cinta), aunque son una forma de vestimenta contemporánea, también tienen un significado cultural muy importante. Yo no sugeriría que una persona no Indígena usara una. Los desfiles incluyen una mezcla de cosas pensadas para todo el mundo y cosas pensadas más para nosotras/nosotros.

CV: ¿Hacia dónde les gustaría que evolucionaran las cosas?

KE: Ahora hay interés en crear una especie de Consejo Internacional de Moda de Pueblos Indígenas, una idea que surgió con Dante Biss-Grayson, de Sky Eagle Collection. Y aunque nosotras creamos esta plataforma, no sentimos que seamos dueñas de la idea de la Semana de la Moda Indígena de Nueva York. Estamos impulsando que más personas se involucren.

LS: Tenemos suficiente comunidad y talento y hemos construido una lista bastante sólida de profesionales creativos Indígenas, aquí en la ciudad, a la que se puede recurrir una y otra vez para seguir construyendo una economía de reciprocidad dentro de nuestra propia comunidad, abriendo nuevas formas de pensar más allá del capitalismo. Yo quiero que nos alejemos de esta idea de que la moda solo existe en relación con el comercio, porque en realidad es una forma de arte.

-- Cristina Verán es investigadora especializada en Pueblos Indígenas a nivel internacional, educadora, estratega de defensa, creadora de redes y productora de medios. También es profesora adjunta en la New York University Tisch School of the Arts.

Korina Emmerich y Liana Shewey, en la boutique Relative Arts, en el Lower East Side de Manhattan. Foto de Lucía Vázquez.