Although the natural heritage of the Indian subcontinent remains largely unstudied and underappreciated, the range and diversity of its biological wealth matches the grandeur and magnificence of its historic civilization. Geological events that took place millions of years ago have created an incomparable diversity of ecosystems. Positioned at the confluence of three biogeographic realms, India's ecosystems harbor African, European, Chinese, and Indo-Malayan elements. Almost every major type of habitat is in India, from the rugged, lonely Himalaya Mountains to the broad, densely populated Gangetic plain; from the lush, green, tropical rain forest of the Malabar coast to the stark deserts of Rajasthan.

In recent years the natural wealth of the Indian subcontinent has begun to attract investigators, naturalists, and conservationists from around the world. Tropical Asia enjoys possibly the richest diversity of life forms on the face of the earth, and the Indian peninsula might well be considered the cornerstone of this Eden. It is estimated that 4 to 5 percent of all known plant and animal species on earth are found in India.

Tourism Turns to Nature

India has lured travelers and inspired writers since the days of Alexander the Great. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as modern tourism expanded, the romance of the British Indian Empire, of princes, palaces, peacocks, and pachyderms, helped create an exotic image that has attracted generations of travelers. Touting its scenic wonders from the Taj Mahal to the Royal Bengal tiger, India has experienced a healthy, expending tourism trade.

Today, tourism is Indian's largest industry, bringing $1.3 billion in foreign exchange earnings - 15 percent of India's total. Ten million people are employed in the tourist industry, with almost three times as many individuals indirectly involved (Marchant 1988).

A growing percentage of this trade is seeking "natural India." Visitors are being drawn back to the forests immortalized by Kipling, and India is expanding the traditional focus of its tourism - its renowned historic monuments and cultural attractions - to include its wildlife and natural landscape.

Trends toward wildlife tourism, both domestic and foreign, are welcomed, for there is no better way to communicate the worth of a country's natural wealth than to allow to others to experience it firsthand. But these valued natural areas cannot withstand unlimited access. Right controls have, in many cases, been implemented by responsible government officials and enlightened tour operators.

Recently, the government, the Pacific Area Travel Association, and organizations such as the Indian Heritage Association and the Tourism and Wildlife Society of India (TWSI), have worked to associate tourism with the preservation rather than desecration of the environment. The Indian Heritage Association's work to save the Taj Mahal from sulfurous wastes and industrial vibration highlights the positive force that tourism can be (Gantzer and Gantzer 1983). Conservation groups are realizing that low-impact, special-interest tourism can be an effective incentive for wildlife protection policies.

This so-called "nature tourism" is based on the enjoyment of natural areas and the observation of nature. Cities and towns are used primarily as arrival and departure points, with visitors concentrating their time in national parks where their activities can be monitored, thus ensuring minimal environmental damage.

As the demand to visit unspoiled places grows, the need to establish management practices that preserve these areas must also grow. Parks and reserves provide the means for achieving adequate control. The Indian government has taken can active role in developing policies for natural areas and providing guidelines for their appropriate use.

Government Conservation Activity

Although the first national advisory body was established in 1952 (the Central Board for Wildlife), the most important conservation initiatives have taken place since the 1970s. Among these are the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, and the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, which increased the number of national parks and sanctuaries from, respectively, 10 and 127 in 1970 to 66 and 300 today.

In 1983, the Indian government formulated and adopted the National Action Plan for Wildlife Conservation. The plan provides for: (1) the establishment of a representative network of protected areas to ensure that all significant biogeographic subdivisions within the country are covered; (2) management of protected areas and habitat restoration aimed at increasing the quality of management and consideration for the local people in and around the wildlife reserves; (3) wildlife protection in multiple use areas to serve community needs (by raising productivity) while enhancing resource conservation; (4) rehabilitation of endangered and threatened species; (5) captive breeding programs designed to reintroduce endangered species back into the wild whenever possible; (6) wildlife education and interpretation aimed at decision makers, students, people living in and around the parks, and the general public; (7) research and monitoring; and (8) domestic legislation and international conventions.

India's national parks and wildlife sanctuaries thus serve to conserve examples of ecosystems that are self-sustaining. They also promote and facilitate research and monitoring on their appropriate use and management, thus providing opportunities and facilities for education and training at all levels. By promoting the appropriate use of the reserve's natural and cultural resources, they assure sustained productivity and promote appropriate, integrated development through sustainable use.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as TWSI play a crucial role in these kinds of conservation efforts. Voluntary agencies can assist in a number of ways, by helping to collect data, forming action and pressure groups, advising the government on legislation and the protection of various species, monitoring legal and illegal trade, and educating the general public. Perhaps most important, NGOs can serve as a liaison between the government and the people and between sister domestic and international conservation groups.

Project Tiger: Its Success and Social Costs

A critical turning point for Indian conservation was the recognition in the late 1960s that the tiger was destined for extinction. The precariously depleted status of the tiger throughout Asia came into sharp focus at the 10th General Assembly of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), held in New Delhi in November 1969. The concern generated among both the conservationists and the Indian government resulted in a series of rapid actions, including a country-wide ban on tiger hunting in July 1970. In 1972 the World Wildlife Fund offered financial assistance and Project Tiger, the largest-ever nature conservation effort in Asia, was launched.

Project Tiger was essentially formulated on an ecosystem concept. The initial proposal had as its basic objective to ensure maintenance of a viable population of tigers in India and to preserve, for all times, areas of biological importance as a national heritage for the benefit, education, and enjoyment of the people. This objective was reiterated by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in her address launching the project in April 1973: "The tiger cannot be preserved in isolation. It is at the apex of a large and complex biotope. Its habitat threatened by human intrusion, commercial forestry and cattle grazing must first be made inviolate."

The initial nine reserves (today there are seventeen) were established with a sizable core area, free from all human use, surrounded by a buffer zone where wildlife-oriented land use are permitted. The various reserves represent a variety of biogeographic types. Management plans included provision for (1) repair of human-made damage and ecosystem restoration; (2) mitigation of limiting factors, such as antipoaching measures, village relocation, and water conservation; and (3) monitoring of and research on the flora and fauna.

Project Tiger has been hailed for its successes, not only for putting the endangered tiger on a course of assured recovery, but also with equal, if not greater appreciation for saving some of India's unique wild ecosystems. Currently, more than 8,000 km2 are under core protection and more than 24,000 km2 lie within buffer areas. The tiger population within the parks has doubled nationally and a number of other endangered species such as swamp deer, elephant, rhino, and wild buffalo have benefited. The diversity of flora and fauna within the reserves overall has been enhanced (Panwar 1987).

Important work remains to be done, however. Rehabilitating these areas has inevitably required that local inhabitants curtail their customary use of the region. These people were toiling on marginal lands, supplementing their livelihood by grazing stock and collecting firewood and edible forest products. This curtailment of community use was to be compensated by alternatives yet to be provided to the local people. At one of the Project Tiger reserves, this community development activity has so far not produced the desired improvement in the economic conditions of the people living in the vicinity.

Ranthambhor National Park

The Ranthambhor reserve, in southeast Rajasthan, is one of nine original reserves. It covers a total area of 825 km (392 km in the core) in a tropical deciduous forest. The topography consists of undulating hills interspersed among six lakes. The climate is subtropical with a rich assortment of flora and fauna. The project is administered by the Forest Department of the government of Rajasthan. It is headed by a field director who is supported by a team of 85 other officers and employees.

The most notable achievements of Project Tiger in Ranthambhor include significant habitat improvement through the relocation of 12 villages to sites outside the park, creating new water reservoirs, and preventing forest fires with subsequent increase in cover. A strong antipoaching program and the enhancement in habitat has led to a marked increase in the tiger population and its prey species such as sambhar, chital deer, and so on. The most recent census (1988) in the park recorded that the number of tigers had increased to 43 from 14 in 1972.

Despite this success, the park is facing a number of problems similar to those experienced in other reserves. In general, the local people have not benefited directly from the park. From their point of view, they have been denied their traditional use of the land - cattle and buffalo grazing, firewood collecting, and collecting building materials for their homes - and have received little in return.

To the people living in these forested regions, agriculture and cattle raising on these marginal lands is the mainstay of their livelihood. Without compensation and alternatives, such pressures on the local environment will continue. Today more than 55,000 cattle reside within the buffer zone of Ranthambhor, a number the exceeds the total of all other herbivores combined. These cattle wander into the core area and create heavy competition for grazing with the tiger's pray base. The park is surrounded by human inhabitants, and four villages remain within the core. People continue to collect fuel wood from the protected forest, and a number of religious pilgrims journey through it to the holy Ganesh temple within the park grounds (TWSI 1988).

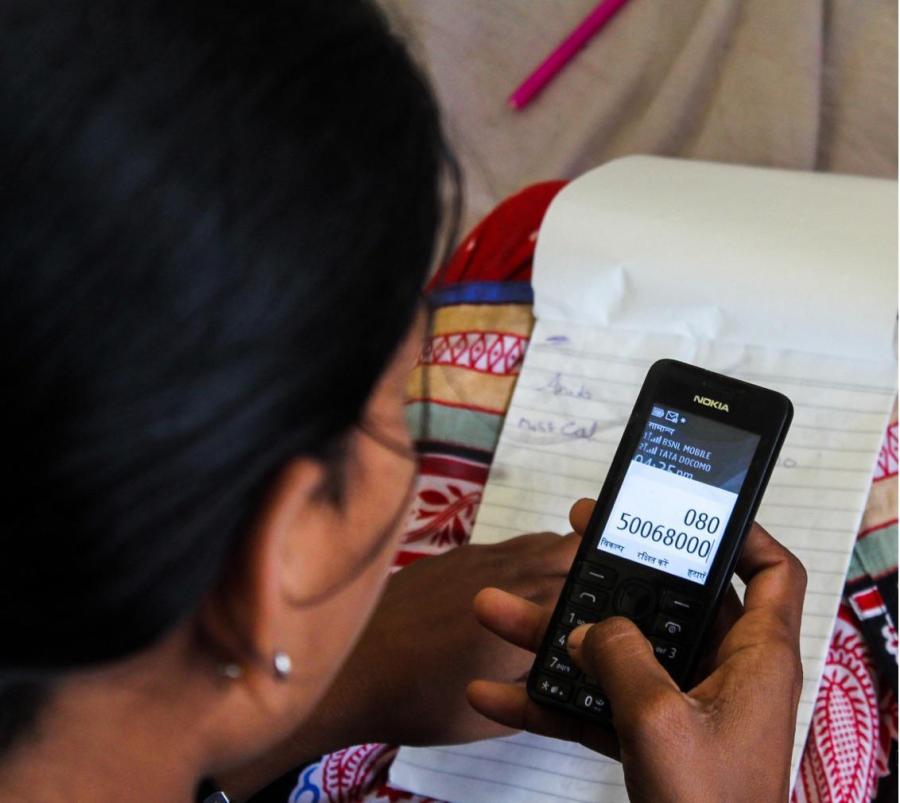

Attempts to compensate villagers for their lost privileges have been unsuccessful because of the lack of resources. Attempts to introduce stall feeding of cattle or to improve their blood stock have failed because there is simply no spare cash available for even the smallest investment. Even plans for introducing new, smokeless chulas (ovens) that can reduce a household's fuel consumption by more than 30 percent did not work because villagers were unable to pay the one-time cost of around 30 rupees (US $2.50) per chula.

There is need of additional resources and better coordination among the programs that already exist. For example, in Ranthambhor the Animal Husbandry Department distributes goats and sheep in villages where the Social Forestry Department distributes saplings. One can imagine the outcome without proper education and coordination.

The successes and problems relating to Project Tiger show clearly that the main thrusts of the conservation effort in coming years must be to ensure that the reserves are managed in concert with the surrounding communities and to provide a strong conservation orientation to community development programs of other government agencies.

A Collaborative Effort in Ranthambhor

The Antaeus Group, a nonprofit educational and research institute (see box on p. 18), has begun to work with representatives from Rajasthan's National Park System and the Tourism and Wildlife Society of India on the Ranthambhor National Park and its surrounding villages to assess the needs of the village people, evaluate current park practices, and support new approaches to reconcile potential conflict between park and local people. The Antaeus Group wants to assist the National Park System in meeting both the needs of the wildlife it was designed to protect and the needs of the Indian people who share its surrounding habitat. Appropriately designed tourism can facilitate this conservation and community development effort.

For example, we have been organizing and leading study missions to northern India and Nepal. These expeditions visit some of the traditional cultural attractions (Delhi, Jaipur, Agra) as well as some of the area's unique natural landscapes. Our primary purpose is to introduce people to India's incredible cultural and biological diversity and to become a positive force in preserving this natural and cultural heritage. Consequently, we focus on sites of important conservation activity and meet with those engaged in preservation efforts. It is our hope that we can increase visitors' appreciation for this amazing country and involve them in local conservation efforts through international advocacy and through providing information, equipment, in-kind services, and even direct financial support.

With each Antaeus expedition we provide a direct donation to the work going on at Ranthambhor. These funds are to be used as the local committee sees fit. Our approach has been to build on the good works of TWSI and others and to facilitate ongoing local efforts at curbing livestock populations, improving cattle breeds, encouraging stall feeding programs and fodder farms, and developing and distributing alternative, more efficient cooking stoves.

In addition, we are looking to engage in a number of other collaborative efforts. A proposal to the US-India Fund is being developed to research and analyze the situation at Ranthambhor and to continue to assist our Indian colleagues there. We are also planning a series of outreach activities including the preparation of reports, community activities, and professional workshops and seminars.

We see our task primarily as educational and view Ranthambhor as an extremely valuable educational resource. We must reach a variety of important audiences with some very critical messages. Conservationists see the area as a place of ecological importance and want to protect its unique species diversity. The area is special in that it is relatively undisturbed and is representative of a type of habitat that is increasingly threatened worldwide. The local residents, on the other hand, see the area as their home, as the provider of their livelihood and of their identity. They are interested in protecting the land so that they can protect their way of life. These different viewpoints are reflected by the respective reactions of the local people and conservationists of proposed activities in Ranthambhor. From our somewhat removed perspective we would like to help bring these divergent views to a mutually beneficial conclusion.

Outreach to the Conservation Community

It is axiomatic that as conservation efforts become successful they automatically conflict with other human interests. Problems initially perceived as biological in nature become political, economic, social, and cultural ones. Conservationists must learn that the future of parks depends upon how quickly alternative resources vital to the local people can be generated. The task for park planners is to explore and foster means of coexistence beyond the park boundary and into the local communities. If this is not achieved, national parks and reserve systems in the developing world will perish.

We must point out to conservationists that these parks and reserves cannot exist in isolation; their continued existence can only be assured with the support of the local people, and their future efforts must include meeting the community's immediate needs. We are planning a number of meetings, workshops and papers on this critical theme, directed to government administrators and park staff.

Outreach to Local People

Local concerns can be diffused by direct communication. We shall sponsor meetings with park authorities, villagers, schoolteachers, and community leaders to discuss local problems and the needs of the national park. These will allow residents to voice their objections and concerns and allow park staff to understand the dimensions of the problems these people face. The park staff, in turn, can explain why demands of local residents, such as grazing or timber gathering, cannot be permitted. The psychological value of this exchange is significant because it allows local villagers to see that they are becoming involved in the park processes that affect them.

It is important to build upon the local education efforts already begun by TWSI. The growing number of domestic and foreign visitors coming to Ranthambhor is making the local people become aware of the importance of their environment. Special events are being planned in the park for all the schoolchildren and teachers in the area. We would like to build small, inexpensive educational centers where the young people of the region can be trained as naturalist guides. Our hope lies with the education of future generations. They will be the teachers, policy makers, park rangers, developers, and parents of the future. TWSI has made significant strides in this direction and we hope our support will amplify their results.

One of the greatest benefits of the national park is its role in conserving soil and water. The lack of an effective conservation education and publicity program is in part responsible for the local communities failure to realize this benefit, and to address this situation a series of community outreach programs is being planned using traveling performers and puppeteers. We would like to increase villagers awareness that their future development is linked to the preservation and enhancement of the environment in which they live. It need hardly be emphasized that the productivity of agricultural lands and cattle in these habitats cannot increase without bringing back the forest cover, because water regimen and cattle fodder depend on it. Local inhabitants must be shown how their long-term interests are best served: by maintaining a sustainable resource base as contained in the protected area.

Outreach to Politicians and Planners

Perhaps the most influential target groups in India are the politicians, professional planners, and administrators whose activities have a bearing on natural ecosystems. Quite often this group takes action because the conservation issues involved appear trivial to them when compared to the immediate benefits they see from a particular development program. Politicians, planners, and decision makers need to learn to appreciate the fact that there is a longterm economic benefit in setting aside development through protecting other life-support systems such as water resources, genetic diversity, sustained yield, or from educational use of the natural resource through tourism.

Policy and guidelines for administering Ranthambhor come from the central government to be administered by the state government. In order for local officials to effect changes, they need the assistance of people at the highest level of influence who understand what needs to be done. Workshops will promote the idea that development needs to be undertaken in an ecologically sensitive manner compatible with natural systems. Protected areas must be considered a necessary part of any sustainable development project.

A specific local matter that needs to be addressed involves park revenues. At present, revenue generated by local park activities goes directly into central government accounts. National policy should be changed so that some park revenue goes directly into developing local communities for agriculture and livestock assistance, building roads, providing schools, and creating medical facilities. Channeling some park fees back to the villagers would demonstrate a certain ownership of the park on their part.

The Message to Tour Operators

It is clearly evident that without sound planning tourism and the development it brings might destroy the very resources on which it is based. Tourism and environmental conservation can peacefully coexist with appropriate guidelines.

Tourism can be a powerful tool for environmental conservation by enhancing public awareness of environmentally sensitive areas and their resources and by mobilizing support to prevent the erosion of such environments. It can also provide immediate economic incentives for preserving them.

As travelers we are among the most privileged of all humanity. With that privilege comes the immense responsibility of respecting and honoring all peoples and all life forms with which we come into contact. A travel ethic of sorts is evolving among responsible tour operators that encourages local guides, landowners, and conservation representatives to develop and implement long-term visitor plans to ensure the sustainable use of their areas.

Our message to tour operators serving Ranthambhor is to subscribe to this evolving code, which mandates that (1) visitors respect local culture and traditional ways of life and be sensitive to the feelings of local people and not intrude on their private lives; (2) visitors not disturb the wildlife and its habitat and maintain minimum distances and noise levels; (3) visitors be as self-sufficient as possible, removing the waste they generate; (4) visitors not buy products that threaten wildlife and plant populations; (5) tours strengthen the conservation effort and enhance the natural integrity of places visited. Tour operators' commitment to these principles and their leadership, understanding, and vigilance is crucial to developing sustainable tourism in natural areas.

In Ranthambhor there is already a realization of the park's carrying capacity for visitors. Access to the park is supposed to be regulated. There is a small network of five viewing routes, each route limited to three vehicles at a time. Wildlife viewing is permitted only for a two-hour period in the early morning and mid-afternoon. As demand increases, perhaps new entry points and larger vehicles could be allowed. As it is today, all visitors enter from one access point and confine their activities to the routes circling three of the park's lakes in small jeeps.

Conclusion

The new developing nature tourism is very conscious of the need to minimize human impact on fragile habitats by supervising and restricting visits. National parks and reserves provide the means of achieving adequate control while tour operators begin to formulate specific guidelines for their own operations. Potentially this kind of low-impact, labor-intensive tourism can serve conservation efforts as well as directly benefit local populations in and around protected areas.

A collaborative effort between The Antaeus Group, representatives of Rajasthan's National Park System, and the Tourism and Wildlife Society of India is designed to being together those interested in wildlife and habitat conservation and the development of local peoples through socially and environmentally responsible tourism. Our goal is to demonstrate that ecological conservation efforts can be compatible with the efforts of indigenous groups to protect their territory and their way of life as well as with tourism. We look forward to continued collaboration with our colleagues in India and the opportunity to facilitate ongoing local efforts to reconcile potential conflict between parks and people.

References

Gantzer, H., and C. Gantzer

1983 Managing Tourism and Politicians in India. International Journal of Tourism Management 4(3):118-125.

Marchant, G.M

1988 India Takes a New Approach. Asia Travel Trade (November): 28-30.

Panwar, H.S.

1987 Project Tiger: The Reserves, the Tigers and Their Future. In R.L. Tilson and U.S. Seal, eds. Tigers of the World: The Biology, Biopolitics, Management, and Conservation of an Endangered Species. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes.

TWSI (Tourism and Wildlife Society of India)

1988 Men vs. Wildlife: Report of Peripheral Villages of Ranthambhor Project Tiger. (unpublished)

About The Antaeus Group

The Antaeus Group is involved in efforts to foster a sense of responsibility for maintaining the earth's biological and cultural diversity and to encourage balanced development and conservation efforts throughout the world. Antaeus Expeditions, as part of The Antaeus Group's educational efforts, offer firsthand experiences of the world's natural environments, wildlife, and human cultures. Their goal is to promote, through socially and environmentally responsible travel, increased appreciation of the world's cultural and biological diversity and to become a positive force in preserving our planet's natural and cultural heritage.. Through Antaeus Expeditions we hope to engender an appreciation of the land and its people and a sense of responsibility toward both. We intend to involve participants in local conservation efforts through international advocacy, providing information, equipment, and in-kind services as well as direct financial support.

For more information, write:

David B. Sutton, Executive Director

The Antaeus Group

P.O. Box 4050

Stanford, CA 94309.

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.