Miles and miles of Cerrado have been cleared and planted with fastgrowing grasses for cattle feed. Photo by Eduardo Amorim on Flickr.It was evening in the Xavante community of Etéñhiritipa in central Brazil as the moon rose over the Serra do Roncador. We had just finished a refreshing bath in the river and were seated against the wall of a house facing the cleared red-earth plaza in the community’s center (clearing the swath of vegetation around the houses and in the central plaza means there are no snakes to deal with near people’s homes). Twilight settled over the thatched houses as the adolescent novitiates sang and danced a dreamed song around the semicircular ring of houses and the adult men gathered in the central plaza for their nightly men’s council.

Miles and miles of Cerrado have been cleared and planted with fastgrowing grasses for cattle feed. Photo by Eduardo Amorim on Flickr.It was evening in the Xavante community of Etéñhiritipa in central Brazil as the moon rose over the Serra do Roncador. We had just finished a refreshing bath in the river and were seated against the wall of a house facing the cleared red-earth plaza in the community’s center (clearing the swath of vegetation around the houses and in the central plaza means there are no snakes to deal with near people’s homes). Twilight settled over the thatched houses as the adolescent novitiates sang and danced a dreamed song around the semicircular ring of houses and the adult men gathered in the central plaza for their nightly men’s council.

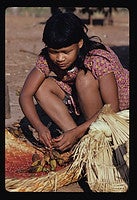

The rhythm of daily life felt almost the same as it did more than 25 years ago when, as a graduate student, I began my ethnographic studies of Xavante peoples among this group. The dramatic changes that are taking place in the central Brazilian plateau seemed far away, almost undetectable at a first glance inside the community. But changes there are, and they especially threaten the land rights of the Xavante people. I was in Etéñhiritipa with Cultural Survival Executive Director Ellen Lutz, who came to learn the challenges Xavante now face and to explore ways that Cultural Survival could support their efforts.  Poré, who lives in Pimentel Barbosa, removes ripe seeds from urucum pods, used to make the red body paint that Xavante and other Cerrado peoples value. Photo by Laura Graham.The Xavante live in the vast Brazilian savanna called the Cerrado, an area the size of the American Great Plains. A Ge-speaking people, they retreated from contact with national society in the mid-1800s and earned a reputation for fierceness and determined isolationism. Xavante groups did not begin to establish peaceful relationships with representatives of national society until 1946. Even then, some groups refused contact until the mid-1960s.

Poré, who lives in Pimentel Barbosa, removes ripe seeds from urucum pods, used to make the red body paint that Xavante and other Cerrado peoples value. Photo by Laura Graham.The Xavante live in the vast Brazilian savanna called the Cerrado, an area the size of the American Great Plains. A Ge-speaking people, they retreated from contact with national society in the mid-1800s and earned a reputation for fierceness and determined isolationism. Xavante groups did not begin to establish peaceful relationships with representatives of national society until 1946. Even then, some groups refused contact until the mid-1960s.

Fifty years after colonization, the Xavante continue many of their traditional cultural practices, and their spiritual and ceremonial lives are rich. They also face tremendous challenges. Their homeland is now just a 12-hour drive from Brasília and lies in the heart of Brazil’s new agricultural and economic engine. The nine small reserves that the government began carving out for the Xavante in the late 1970s today seem like islands in a sea of soy. And agribusiness has its sights set on even these small reserves where, in indigenous areas such as these, the rich and unique Cerrado ecosystem is still intact.

While large-scale agriculturalists and related corporations are reaping enormous profits from Mato Grosso’s burgeoning soy industry and making plans for multimillion-dollar development projects, many Xavante don’t have enough to eat, and those who live in the smallest of the Xavante areas can’t find sufficient game or even palm fronds to construct their thatched homes. The health situation in Xavante areas is abysmal: infant mortality is high, well above the regional and national averages and close to that of Northeastern Brazil, the nation’s poorest region. Xavante mortality rates are high because they are exposed to many infectious diseases and have poor health care; an epidemic of hypertension and diabetes is imminent.

Xavante are one of many central Brazilian groups whose homelands and livelihoods have been severely affected over the last two decades by the proliferation of colossal agro-industry. In some areas it is soy; in others, sugarcane for biofuels; and in still others, fast-growing eucalyptus for firewood to process soy oil in factories.

“The Cerrado is a source of life to the Indigenous community,” says Elcio, from the Terena village of Cachoeirinha. “It is very important to us, and we worry about the devastation of the Cerrado, especially in our region, where the farmers are cutting the forests down. The Cerrado has enormous biodiversity, and it sustains our lives, because our foods come from the Cerrado: it is where we hunt and fish, collect fruits and honey. Burning down the forests is also threatening the biodiversity of the Cerrado. The burnings are destroying the guavira, a delicious fruit that we eat and can also sell.”

The Xavante are more fortunate than some because they live in legally protected reserves—even if those protections are frequently disregarded and the areas are small. Many other groups live on lands that have yet not been legally demarcated. For many, their claims have been languishing for decades in the drawers and filing cabinets of the government agency responsible for granting Indigenous Peoples legal title to their lands.

Ellen and I, along with our companions, Hiparidi Top’tiro, a Xavante leader from the Sangradouro Reserve, and activist Daniela Lima, made the trip from Brasília to the Xavante areas in less than a day. Paved roads carried us to within about 40 miles of the Pimentel Barbosa reserve. This was a journey that in 1982 had taken me a minimum of three days (usually more), traveling in a sturdy four-wheel-drive truck over rough dirt roads and unstable bridges, often no more than two planks precariously set over logs. In the rainy season, when torrential downpours hammer the Cerrado, the road was frequently impassable, and washed-out bridges were common. On this trip, we made rapid time. Our small sedan wove in and out between heavily laden trucks that were barreling down the highway at speeds that made me nervous. These immense truck caravans were transporting agricultural produce, particularly soybeans, out of Mato Grosso, Brazil’s largest soy-producing state, to ports and commercial centers where most of these crops would be exported, mainly to markets in Europe, China, and Japan.

Our journey too k us past miles and miles of deforested Cerrado fields, much of it owned by large and powerful farming and ranching corporations. We passed huge grain elevators, silos, and storage facilities and billboards with transnational names: Cargill, Bunge, ADM, Maggi, Monsanto. Towns that I previously knew as small hamlets had mushroomed into sizeable cities; municipalities in this region are some of the fastest-growing cities in the nation.

k us past miles and miles of deforested Cerrado fields, much of it owned by large and powerful farming and ranching corporations. We passed huge grain elevators, silos, and storage facilities and billboards with transnational names: Cargill, Bunge, ADM, Maggi, Monsanto. Towns that I previously knew as small hamlets had mushroomed into sizeable cities; municipalities in this region are some of the fastest-growing cities in the nation.

The galloping, massive growth in the agroindustry is putting enormous pressure on the Xavante and other Indigenous groups. The prevailing attitude in the region is pro-development, pro-agribusiness. Anyone who takes an alternative position meets strong resentment and antagonism. This is especially true for Indigenous Peoples who, in defending their constitutionally granted rights to territory, clean environment, and the ability to live according to their traditional ways, are perceived as presenting obstacles to progress.

The Brazilian Cerrado extends across the vast central Brazilian Plateau, stretching over approximately 800,000 square miles, almost one third of the nation’s land mass and spanning 12 states. Its total area is equivalent to the combined area of Spain, France, Germany, Italy, and England (or, if you prefer, three times the size of Texas). It is one of the world’s most biologically diverse tropical savanna regions and the nation’s second major biome, after the Amazon rainforest. Conservation International identifies it as a “Conservation Hotspot,” one of “the richest and most threatened reservoirs of plant and animal life on Earth.” The Cerrado houses the watersheds for three of South America’s major river basins: the Amazon, São Francisco, and Paraná/Paraguai. As Xavante leader Cipassé Xavante says, “The fight to save the Cerrado isn’t just for us, it is for all humanity.” What happens in the Cerrado has broad human and planetary effects.

Soy agribusiness began to aggressively expand into Brazil’s central western Cerrado in the late 1980s, when soy varieties that could tolerate the tropical climate became commercially available. This accelerating agricultural boom, together with huge related infrastructure development projects (road construction, hydroelectric dams, colossal hydro-engineering projects to transform rivers into water highways), as well as illegal mining and timber extraction in Indigenous areas, is destroying the fragile Cerrado environment and having devastating effects on the region’s Indigenous inhabitants.

Socially and culturally diverse Indigenous Peoples have lived in the Cerrado for centuries, but reliable demographic information on the current Indigenous populations does not exist. Brazil’s central-west region alone (the states of Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Goiais, Tocantins) is home to some 53,000 Indigenous people who belong to 42 distinct ethnic groups. All of these groups are confronting serious challenges, and some are responding by building alliances with members of other Indigenous groups and other traditional peoples, and also with national and international organizations like Cultural Survival. In the face of formidable foes and challenges, they are asserting themselves to take control over processes that are influencing their lives.

The Rise of Colonization Small swidden, or slash and burn, gardens recycle forest nutrients and are not destructive to the Cerrado, unlike mass monocrop plantings that demand large amounts of chemicals. Photo by Guia D’Chapada (Flickr).During the 1960s and into the 1980s, the Brazilian government used large-scale colonization schemes and generous fiscal incentives to attract settlers and commercial cattle ranching from the south into remote Cerrado regions. As the frontier moved westward, there were increasing conflicts between settlers and Indigenous Peoples, and communities were devastated by new diseases, like measles, against which they had no immunity. In a pattern repeated over and over, government agents or missionaries used those problems to attract distressed Indigenous groups to specific locales—government posts or missions—where they received sanctuary and medical treatment. With a region’s original inhabitants corralled into defined areas, the state then sold their lands, with titles certifying the land as “free of Indians.”

Small swidden, or slash and burn, gardens recycle forest nutrients and are not destructive to the Cerrado, unlike mass monocrop plantings that demand large amounts of chemicals. Photo by Guia D’Chapada (Flickr).During the 1960s and into the 1980s, the Brazilian government used large-scale colonization schemes and generous fiscal incentives to attract settlers and commercial cattle ranching from the south into remote Cerrado regions. As the frontier moved westward, there were increasing conflicts between settlers and Indigenous Peoples, and communities were devastated by new diseases, like measles, against which they had no immunity. In a pattern repeated over and over, government agents or missionaries used those problems to attract distressed Indigenous groups to specific locales—government posts or missions—where they received sanctuary and medical treatment. With a region’s original inhabitants corralled into defined areas, the state then sold their lands, with titles certifying the land as “free of Indians.”

One of the most egregious examples of purging Indigenous Peoples from their lands occurred in the Xavante area known as Marãwaitsede, located in the region of the Suya-Missú River near what is now the Xingu National Park. (The park is Brazil’s “postcard” Indigenous Territory, an area of 108,000 square miles that is home to approximately 4,700 people Indigenous Peoples belonging to 14 distinct groups.) After a São Paulo-based rancher fraudulently purchased lands inhabited by Xavante, he flew an airplane over the area everyday and dropped food in a specific location. Eventually the Xavante relocated to the site to receive rations. The rancher then moved the group multiple times and finally settled it close to ranch headquarters, where he forced the Xavante to work for food, and subjected them to continuous harassment by the ranch’s non-Indigenous employees. Conditions for Xavante deteriorated so severely that, in 1966, the owners—at that point the powerful Italian-based Olmetto group, whose corporate land holdings reached 6,000 square miles—in collaboration with Salesian missionaries, the government Indian agency, and the Brazilian Air Force, solved their “Indian problem” by airlifting the remaining Xavante some 250 miles away to the Salesian mission at São Marcos. Within two weeks after their arrival, more than 100 Xavante died of a measles epidemic.

In 1994, Xavante from this area finally won a long battle to recoup some of this land when the state demarcated the Marawãitsede Indigenous Territory. But despite the ruling, ranchers who had moved onto the land refused to leave or allow the Xavante to move back to their territory. They even encouraged settlers to take their place and deforest large tracts. When, in 2004, a determined Xavante group attempted to enter their lands, they were prevented by armed gunmen. The refugees set up camp on the opposite side of the dirt highway (BR-158) and lived for 11 months in improvised shelters. Three babies died of pneumonia exacerbated by the incessant dust from camping alongside the road. When a team carrying out a study for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights attempted to reach the area by road, ranchers burned bridges in an attempt to stop them. The team hired planes and reached the area by air. This area is still plagued by conflict, and powerful ranchers continue to challenge the Xavante's rights to this land in the courts.

Cattle ranchers continue to deforest huge areas of Cerrado lands for pasture around Indigenous areas as well as within them. Deforestation and the aggressive, intrusive grasses that ranchers plant for cattle severely disrupt the Cerrado flora and fauna, reducing game populations that are important sources of protein in Native peoples’ diets. And because hunting is central to many important ceremonials, lack of game has forced many groups, such as the Parecí of western Mato Grosso, to abandon traditional activities that are fundamental to their social organization and culture. Suptó, who is a leader of the Pimentel Barbosa community, sings one of his dreamed songs. His earplugs act as “antennae,” enabling him to tune in to the immortals in his dreams. His forehead and hair are painted with highly valued red urucum paint. Photo by Laura Graham.Prior to Brazil’s new constitution of 1988, state policy was directed toward assimilating Indigenous Peoples into the nation’s social fabric and economy (see page 41 for more on this). In the Cerrado area, the government attempted to transform Indigenous Peoples into capitalist ranchers and commercial agriculturalists. For example, in the 1970s, when many Cerrado ranchers were turning to commercial rice cultivation for domestic markets, the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) implemented colossal mechanized rice cultivation projects in Xavante areas. The state used these projects to justify the creation of their reserves. Instead of “wasting” this land on Indigenous Peoples, these areas (along with Indigenous labor) would contribute to the region’s GNP just like other commercial ranches in the region. Many large-scale ranchers and agriculturalists oppose the creation or amplification of Indigenous reserves because, they argue, it removes potentially productive lands from development.

Suptó, who is a leader of the Pimentel Barbosa community, sings one of his dreamed songs. His earplugs act as “antennae,” enabling him to tune in to the immortals in his dreams. His forehead and hair are painted with highly valued red urucum paint. Photo by Laura Graham.Prior to Brazil’s new constitution of 1988, state policy was directed toward assimilating Indigenous Peoples into the nation’s social fabric and economy (see page 41 for more on this). In the Cerrado area, the government attempted to transform Indigenous Peoples into capitalist ranchers and commercial agriculturalists. For example, in the 1970s, when many Cerrado ranchers were turning to commercial rice cultivation for domestic markets, the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) implemented colossal mechanized rice cultivation projects in Xavante areas. The state used these projects to justify the creation of their reserves. Instead of “wasting” this land on Indigenous Peoples, these areas (along with Indigenous labor) would contribute to the region’s GNP just like other commercial ranches in the region. Many large-scale ranchers and agriculturalists oppose the creation or amplification of Indigenous reserves because, they argue, it removes potentially productive lands from development.

For Xavante, the rice projects were immensely destructive: they created massive technological dependency, exacerbated tensions within and across communities, and, since Xavante substituted rice for nutritious traditional foods, dramatically altered their diet. Malnutrition is now a serious problem, and new diseases are endemic, especially hypertension and diabetes, which are associated with excessive reliance on refined foods and the new sedentary lifestyle. The projects also provided opportunities for corrupt Indian agents to siphon monies in every type of financial transaction, from equipment repair to the sale of crops harvested from Xavante lands. Although these projects were eventually abandoned in the late 1980s, many of the problems they created persist.

1990s – The Soy Boom

Commercial agriculture in the central Brazilian Cerrado began with rice and some soy in the 1970s and exploded into a massive export-oriented agro-industry during the late 1980s and 1990s. Soybean cultivation is highly mechanized, capital intensive, and uses large amounts of chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides. Its explosion in the Cerrado coincided with increased global demand in the wake of the mad-cow scare, when Europeans turned to soy for high protein animal feed, and with the expansion of world markets for soy oil, especially in China and Japan. In 2000, Mato Grosso became the country’s leading soy-producing state, and in 2004, Brazil displaced the United States as the world’s leading soy-exporting nation. In Mato Grosso, the area dedicated to soy cultivation increased 81 percent in just three years, between 1991-1994. This area nearly doubled again by 2003, and estimates indicate that the state has the potential to plant 10 times that amount—an area almost the size of California.

The environmental and social consequences of this immense and rapid agricultural explosion are staggering, especially for the region’s vulnerable Indigenous inhabitants, particularly those who do not have legal title to their land. Although Brazil’s constitution guarantees Indigenous Peoples the right to permanently occupy lands they traditionally inhabited, the government has been lamentably slack in carrying out its obligation to identify and legally demarcate those lands. In many cases, large landholders and corporations tie up the land claims in lawsuits that can drag on for years and, in some cases, such as Serra Raposa do Sol in Roraima (see page 46), for decades.

And, of course, while the cases are being decided (or not decided), the landholders and corporations can continue developing and profiting from Indigenous land. They build roads, fences, silos, warehouses, buildings, and sometimes even cities in areas that Indigenous Peoples claim. These “improvements” reduce the likelihood that the government will have sufficient political will or the ability to compensate developers for the cost of their investments, and this increases the likelihood that the state will concede to the more powerful party.

There are many cases, like the Xavante in Marãwaitsede who ended up camped on the roadside, in which farmers and ranchers refuse to leave Indigenous lands, even after they have received compensation. One notable case happened on the Ilha do Bananal, an island the size of New Jersey in the middle of the Araguaia River that is home to Karajá, Javaé, and Ava Canoeiro. Despite the ranchers being compensated for having to move, their cattle remain on the island degrading the environment and polluting the waters. Pará Miri is a 10-year-old Guarani girl. Many Guarani have been displaced from their Cerrado territories and live in other parts of Brazil now. Photo by Gregory Smith.Indigenous groups that challenge powerful landholders are subjected to tremendous pressure. Sometimes they even become martyrs to their cause. In 2007 and 2008, three Xacriabá leaders were assassinated over land disputes. In Mato Grosso do Sul, where Guarani Kaiowa, Nãndeva, and other Native communities are squeezed into tiny areas, 80 Indigenous people are imprisoned. Indigenous Peoples in this region suffer extreme social disorganization, and the incidence of suicide is disturbingly high. Eliso da Lopes is one such leader who, because of persecution from ranchers, has not seen his family in over a year. “We want our land returned so that we can plant and produce,” he says. “Even though this is our land we are living on the edge of an interstate highway. This is a sad situation, but we are not going to pull back. If the ranchers kill one Indigenous leader, 1,000 leaders will arise.”

Pará Miri is a 10-year-old Guarani girl. Many Guarani have been displaced from their Cerrado territories and live in other parts of Brazil now. Photo by Gregory Smith.Indigenous groups that challenge powerful landholders are subjected to tremendous pressure. Sometimes they even become martyrs to their cause. In 2007 and 2008, three Xacriabá leaders were assassinated over land disputes. In Mato Grosso do Sul, where Guarani Kaiowa, Nãndeva, and other Native communities are squeezed into tiny areas, 80 Indigenous people are imprisoned. Indigenous Peoples in this region suffer extreme social disorganization, and the incidence of suicide is disturbingly high. Eliso da Lopes is one such leader who, because of persecution from ranchers, has not seen his family in over a year. “We want our land returned so that we can plant and produce,” he says. “Even though this is our land we are living on the edge of an interstate highway. This is a sad situation, but we are not going to pull back. If the ranchers kill one Indigenous leader, 1,000 leaders will arise.”

Some ranchers have taken a more insidious approach to the issue. Among the Parecí of Mato Grosso, for example, neighboring farmers convinced some leaders to become “agricultural partners,” even though commercial agriculture within Indigenous areas is illegal. Instead of standing up for Indigenous rights, the state governor, Blairo Maggi, a millionaire farmer whose Maggi Group is the world’s largest soy producer, condoned and officially recognized these arrangements. In 1995 the Parecí agreed to allow 130 acres to be planted, an area that has expanded each year. Despite using the term “partners” to describe the Parecí, the farmers take 98 percent of the profits, leaving only 2 percent for the Parecí from the soy grown on their lands with their labor.

Governor Maggi is known in Brazil as O Rei da Soja, “the King of Soy,” but environmentalists call him “the King of Deforestation.” Mato Grosso leads Brazilian states in the number of agricultural burnings and the rate of deforestation. One hundred and fifteen thousand square miles of forest and savanna (an area the size of Arizona) have been replaced with plantations in the last twenty years, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

Deforestation, especially around the headwaters of rivers and streams, causes severe erosion and increases pollution. During the rainy season heavy rains wash toxic chemicals used in soy agriculture—like the Monsanto herbicide Roundup—directly into rivers where Indigenous Peoples drink, bathe, and catch fish. Because Cerrado soils are acidic and nutrient poor, they demand large amounts of lime and chemical fertilizers to be productive. These, as well as pesticides used in intensive monocropping, seep into water supplies and contaminate groundwater, making even well water dangerous. In the Guarani Aquifer, the world’s largest, contaminants have reached 80 percent of the level acceptable for human consumption.

Chemicals are also dropped or carried by wind onto Indigenous lands. This happened during the last planting season in the Xavante territory of Sangradouro, and Paulo Supretaprã, leader of Etéñhiritipa, reports that this also happens in the Pimentel Barbosa Indigenous Territory. Also, since Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio da Silva, lifted the ban on genetically modified organisms in August 2003, soy farmers plant modified varieties immediately next to, and sometimes inside Indigenous areas, even though their environmental and human impacts are unknown. As Paulo Cipassé says (see page 43) Xavante are concerned that game animals they hunt and eat may be ingesting toxic substances outside of Indigenous areas. With plans to expand sugarcane planting and installation of factories for converting this crop into biofuels, pressure on Indigenous territories is likely to increase in the future.

Reshaping the Cerrado In preparation for the ear piercing ceremony that initiates them into adult society, Xavante boys spend weeks in the river hitting the water in a choreographed splashing display. Photo courtesy of Laura R. Graham.With soybean production booming, at more than 4.5 million tons per year in Mato Grosso alone and predictions that production will continue to rise, Brazil has plans for huge infrastructural projects—part of a state plan known as Avança Brasil (“Forward Brazil”)—to make the region more accessible and transport the huge harvests to ports and commercial centers. The Tocantins-Araguaia Hidrovia, also known as the Central-Northern Multimodal Transport Corridor, is a multi-million dollar project that would transform the most extensive river basin of central Brazil and the eastern Amazon into a commercial waterway to support barge convoys mostly for transporting soy, but also carrying agricultural toxins, which makes Indigenous Peoples very nervous. In total, the project would alter 1,700 miles of the Tocantins-Araguaia-Rio das Mortes river system. It includes large-scale engineering works including hydroelectric facilities, locks, and dams and the construction of new ports. Two of the planned “small” hydroelectric projects will be constructed in or next to the Xavante areas of São Marcos and Sangradouro, and the project will directly affect the Xavante territories of Areões and Pimentel Barbosa, where Ellen Lutz and I spent the last night of our Xavante trip. A recently constructed dam next to the Parabubure reserve, one of many planned on headwaters to the Xingu River, is already operating.

In preparation for the ear piercing ceremony that initiates them into adult society, Xavante boys spend weeks in the river hitting the water in a choreographed splashing display. Photo courtesy of Laura R. Graham.With soybean production booming, at more than 4.5 million tons per year in Mato Grosso alone and predictions that production will continue to rise, Brazil has plans for huge infrastructural projects—part of a state plan known as Avança Brasil (“Forward Brazil”)—to make the region more accessible and transport the huge harvests to ports and commercial centers. The Tocantins-Araguaia Hidrovia, also known as the Central-Northern Multimodal Transport Corridor, is a multi-million dollar project that would transform the most extensive river basin of central Brazil and the eastern Amazon into a commercial waterway to support barge convoys mostly for transporting soy, but also carrying agricultural toxins, which makes Indigenous Peoples very nervous. In total, the project would alter 1,700 miles of the Tocantins-Araguaia-Rio das Mortes river system. It includes large-scale engineering works including hydroelectric facilities, locks, and dams and the construction of new ports. Two of the planned “small” hydroelectric projects will be constructed in or next to the Xavante areas of São Marcos and Sangradouro, and the project will directly affect the Xavante territories of Areões and Pimentel Barbosa, where Ellen Lutz and I spent the last night of our Xavante trip. A recently constructed dam next to the Parabubure reserve, one of many planned on headwaters to the Xingu River, is already operating.

In addition, the project will affect at least six other Indigenous groups: the Apinajé, Javaé, Karajá, Krahó, Krikati and Tapirapé. In all, the Hidrovia would directly affect the lives of more than 10,000 Indigenous people who depend on the river’s flora and fauna for their livelihoods. But the Indigenous Peoples are fighting the project, and a lawsuit filed by the Xavante of Pimentel Barbosa in collaboration with the Brazilian organization, Instituto Socioambiental, has delayed the work. It is not clear, though, whether they will be able to stop it.  Expelled from their lands, Guarani camp precariously while they wait for their situation to be resolved. Many Cerrado peoples have been forced to live on roadsides while they fight for their lands. Photo by Naqillum (Flickr).Although Ellen and I only visited a few of the 200 Xavante communities that exist today, we were heartened to learn about many positive projects that Xavante are undertaking to improve conditions in their reserves. Cipassé, the leader of the Wederã community in Pimentel Barbosa, gave us a tour of a recently inaugurated school in his community that had been built with government funds, with state-of-the-art kitchen equipment and a room ready for computers. He also told us of the community’s project to manage, and hopefully increase, the population of white-lipped peccary in the reserve (see Cipassé’s article, page 43). Wederã and many other Xavante communities are also undertaking projects, often in collaboration with NGOs, that validate traditional knowledge of Cerrado plants, many of which have medicinal properties. They want to revitalize collecting and processing practices that have been abandoned and encourage the eating of nutritious Cerrado foods. Small projects like these, which can make a tremendous difference in Indigenous Peoples’ lives, are underway in many Indigenous communities throughout the Cerrado. The Krahó, for example, are helping to enrich the environment by participating in a Cerrado fruit project and earning some income at the same time.

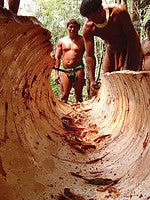

Expelled from their lands, Guarani camp precariously while they wait for their situation to be resolved. Many Cerrado peoples have been forced to live on roadsides while they fight for their lands. Photo by Naqillum (Flickr).Although Ellen and I only visited a few of the 200 Xavante communities that exist today, we were heartened to learn about many positive projects that Xavante are undertaking to improve conditions in their reserves. Cipassé, the leader of the Wederã community in Pimentel Barbosa, gave us a tour of a recently inaugurated school in his community that had been built with government funds, with state-of-the-art kitchen equipment and a room ready for computers. He also told us of the community’s project to manage, and hopefully increase, the population of white-lipped peccary in the reserve (see Cipassé’s article, page 43). Wederã and many other Xavante communities are also undertaking projects, often in collaboration with NGOs, that validate traditional knowledge of Cerrado plants, many of which have medicinal properties. They want to revitalize collecting and processing practices that have been abandoned and encourage the eating of nutritious Cerrado foods. Small projects like these, which can make a tremendous difference in Indigenous Peoples’ lives, are underway in many Indigenous communities throughout the Cerrado. The Krahó, for example, are helping to enrich the environment by participating in a Cerrado fruit project and earning some income at the same time. Kalapalo men fashion a canoe from an immense Cerrado log. Photo by EGiacomazzi (Flickr).We were glad that our trip provided opportunities for our companions, Hiparidi Top’tiro and Daniela Lima, to spend time with Xavante leaders and community members. Among other things, they discussed a project known as Marãna Bödödi, or Forest Path, which would unite the disparate Xavante and Bororo Indigenous territories that lie along the Rio das Mortes into a single contiguous protected area.

Kalapalo men fashion a canoe from an immense Cerrado log. Photo by EGiacomazzi (Flickr).We were glad that our trip provided opportunities for our companions, Hiparidi Top’tiro and Daniela Lima, to spend time with Xavante leaders and community members. Among other things, they discussed a project known as Marãna Bödödi, or Forest Path, which would unite the disparate Xavante and Bororo Indigenous territories that lie along the Rio das Mortes into a single contiguous protected area.

As part of our effort to understand ways that Cultural Survival may best support Xavante, we met with staff from the National Indian Foundation’s department of territorial affairs and the office of the Attorney General that deals with Indigenous affairs. It was very encouraging to find that the officials we met were very supportive of this and other Indigenous efforts to protect their lands.

Brazil’s constitution is a strong weapon for Indigenous Peoples, but putting their rights into practice takes dedication and very long, hard work. The Xavante Warã Association and an expanding network called the Mobilization of Indigenous Peoples of the Cerrado are taking action to advance the struggle of Indigenous Peoples of the Cerrado. Kuiusi Kisêdjê, leader of the Ngojwere community in the Xingu, spoke for many when he said, “We fight to recoup this land because it is sacred to us; our ancestors are buried here. A lot of people think that we only care about money, but what we want is our land.”